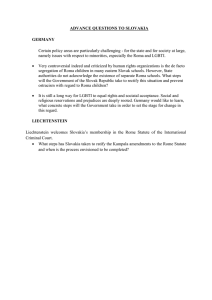

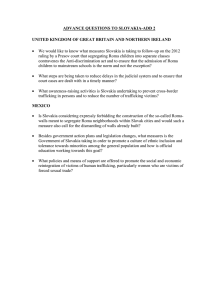

Study on "The social and employment situation in Slovakia and

advertisement