Doubt: a Wittgensteinian approach

advertisement

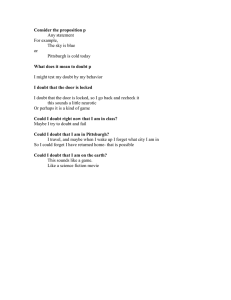

© Michael Lacewing Doubt: a Wittgensteinian approach Scepticism can get started by reflecting on how we know what we think we know. We discover judgments it seems silly to doubt, but for which we seem to have no clear justification, for example the existence of a world outside my mind. Couldn’t my experience be identical if I were dreaming or if I were a brain in a vat being ‘fed’ experiences? Do I know that none of these apparent possibilities is the case? So how can I say I know there is an external world? But if I don’t know that, how can I know anything? These apparently unjustified assumptions form an unquestioned background to our usual enquiry about the world. Wittgenstein gives a variety of examples of the sorts of claims we just don’t doubt: ‘That is a tree’, ‘12x12=144’, ‘I have never been on the moon’, ‘I have two hands’, ‘The world existed before my birth’, and ‘These are English words’. If we are certain of anything, we are certain of these examples (On Certainty, 250). Surely, also, if we know anything, we know these to be true. Don’t we? THE PECULIARITY OF SCEPTICISM Philosophical sceptical doubts are peculiar. They don’t make sense in everyday circumstances. Of course, if I’ve just been in an accident, and can’t feel my left arm, doubting whether I have two hands does make sense! But the sceptic is not interested in these propositions when we have an ‘everyday reason’ to doubt them. The sceptic’s reason for doubting them does not arise from a particular context - it is a general doubt as to their justifiability. The sceptic admits that there is no everyday reason to doubt whether there is an external world. We may wonder whether this sort of sceptical doubt is doubt; it has no practical consequences, after all. A philosophical sceptic is not an extreme variety of the cautious person! Yet the sceptic insists that her doubts are relevant; the standards of ‘knowing’ are not being changed here - we should know that we are not brains in vats to know that ‘This is a hand.’ Surely the reason this sort of doubt is peculiar is not because it is illegitimate, but because we are not usually reflective in this way (for a start, it’s not practical). And yet we might still think that it is ‘unreasonable’ to have such doubts. However, just as the doubt seems peculiar, so does the claim ‘I know this is a hand’. A claim to know implies the speaker believes she has genuine information that others may lack. That might explain it’s peculiarity; but Wittgenstein goes further and suggests that it is a mistake to say ‘I know this is a hand’. Knowledge claims require grounds. But what evidence or expertise is there for ‘This is a hand’?! What checks are possible? Grounds need to be independent of and more certain than the knowledge-claim, and they provide reasons for thinking it true. WHAT DO I ‘KNOW’? We may diagnose the peculiarity of ‘I know this is a hand’ as indicating, not that we don’t know the background assumptions of our usual enquiries, but that we are rarely, if ever, in a position to assert them sensibly. If knowledge requires grounds, then perhaps all our experience grounds such claims. This move doesn’t work, though. That I see that this is a hand is not good grounds for the claim that I know this is a hand in the light of the sceptical challenge – for on what grounds can I assert that my experience is a good guide to how things really are? Not my experience, for this is to beg the question! I can only say that it appears that this is a hand. And without knowing that appearance is a reliable guide to reality, this is not enough to support my claim that I know this is a hand. Such general claims as appearance is a good guide to reality seem insupportable because nothing can count as evidence for them – all evidence presupposes them. My certainty is not enough to provide knowledge, and pointing to the unreasonableness of sceptical doubt does not meet the sceptical challenge, which does not suggest that there is any reason to believe in sceptical possibilities, but requests that we rule them out as possibilities. As it seems that we cannot do this, we must reconsider the idea that we do not know these basic assumptions, and that exempt from knowledge, they are equally exempt from doubt. MEANING, DOING AND KNOWING Wittgenstein notes that we are certain of nothing more than these background assumptions, not even of the meaning of words (On Certainty, 126). In fact, they are often used in the teaching of meaning. ‘This is a hand’ could be replaced by ‘This is called a ‘hand’’. So we can challenge: ‘‘I don't know if this is a hand.’ But do you know what the word ‘hand’ means?’ (OC 306). Someone is not able to mean things by what she says until she has mastered the language-game within which she wants to speak. This enables us to argue that sceptical doubt is literally meaningless. Doubt, like all linguistic activity, presupposes the mastery of a language-game. I learned what ‘hand’ means by believing someone ‘older and wiser’ when they said ‘this is a hand’. But the sceptic’s situation of doubt is similar to the circumstances under which I learnt ‘hand’, so ‘If I wanted to doubt whether this was my hand, how could I avoid doubting whether the word ‘hand’ has any meaning?’ (369). Furthermore, to have mastered the language game is not simply to have acquired a certain set of beliefs. Being able to mean and to understand are practical capacities, tied to what we do: The meaning of a proposition is its use within a practice; in the case of talk of physical objects, this is usually a matter of description and judgment. Our background assumptions show us how words are used. It might seem strange that such specific judgments as ‘This is a hand’ could play such a role. However, Wittgenstein argues that ‘The truth of certain empirical propositions belongs to our frame of reference.’ (OC 83) With these sorts of statements, my ability to express true statements is a measure not simply of my grasping the truth, but of my understanding these statements. I cannot make a mistake about them because if I go wrong, either my meaning or my sanity (in either case, one’s mastery) is in question. And this provides an answer to scepticism: quite literally, ‘Doubt gradually loses its sense’ (OC 56). Doubting them deprives those very words of their meaning as it undermines the system which constitutes their meaning. However, as a result of their role in defining meaning, there are no independent grounds for such background judgments; they help define the terms one could use in the grounds. Because we cannot give grounds for them, we cannot be said to ‘know’ them. They cannot play the role of a proposition being ‘tested’ for truth. ‘‘Knowledge’ and ‘certainty’ belong to different categories....we are interested in the fact that about certain empirical propositions no doubt can exist if making judgments is to be possible at all.’ (OC 308) A SCEPTICAL RETURN But now it is the sceptic’s turn to suggest that there is something odd going on. It seems that we can make sense of the idea that someone could be in a better position than I am regarding that bottom line of assumptions - that my experience is a tolerable guide to the external world. This idea is expressed by the sceptical possibilities that I am a brain-in-a-vat or I’m dreaming. But notice that the mad scientist or someone who is monitoring my dreams does not have a fully superior perspective, because their own position is no better off against sceptical possibilities than mine. Though they could say that, within their experience, my experience is not a reliable guide to reality, they cannot say that their experience is any more reliable! The idea of a superior perspective regarding my experience is not strictly unintelligible; but the idea of a superior perspective per se, is. But isn’t this enough? Doesn’t this still show that, despite what Wittgenstein argues, the possibility remains that I could be wrong, and I cannot know that I am not. It looks like a stand-off between Wittgenstein and the sceptic. But here is one reason to think it is not. The sceptic started by assuming that our background assumptions were factual, and so could be doubted. Without this, it is difficult to get scepticism going. But Wittgenstein argues that this first move is wrong. And if he is right, sceptical possibilities can’t even arise to then cast doubt on our experience. But Wittgenstein’s solution is hard to accept. Not only does it mean that we do not know such statements as ‘This is a hand’, but they do not even describe reality. Instead, they provide examples of what words mean: ‘‘I know this is a hand.’--And what is a hand?--’Well, this, for example.’’ (OC 268) The circularity is clear. If ‘this’ is a hand by definition, saying that ‘this is a hand’ is not to describe anything. It is more similar to asserting an analytic truth, such as ‘Bachelors are unmarried’. It is true that bachelors are unmarried, but not in virtue of the sentence describing bachelors. Analytic truths define the meanings of the terms used. Our background assumptions likewise define the meanings of the words we use, delimiting their use in our practices. They therefore can’t be said to describe the world. The best response to this is perhaps to say that on the occasions on which ‘this is a hand’ is used to define what ‘hand’ means, then the sentence doesn’t describe the world. But there are other occasions when it could be used, e.g. on an archaeological dig, when it does describe the world. On those occasions, we can provide evidence (there are the right number of bones about the right size, etc.), so we can meaningfully doubt the claim and we can be said to know it. But the reasons for doubt in such situations can only be everyday ones, the sort that scepticism is not interested in. This dual use for sentences like ‘this is a hand’ explains why we feel both that it describes the world (sometimes it does), but that it can’t be doubted (sometimes it can’t). I think this is helpful where it can be applied. But it can’t work for all the examples Wittgenstein gives. Is ‘the world existed before my birth’ ever used to give the meanings of the terms? There are many ‘background assumptions’ that guide how we use language which are not close enough to analytic truths for us to divide them neatly into two uses. But Wittgenstein still wants to say they don’t describe the world. And so we must end inconclusively: If we can make sense of the relation between the ‘background assumptions’ of our practices and reality being proposed, we will have an answer to scepticism.