Comparison of Powertrain Configuration for Plug

advertisement

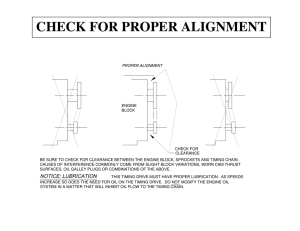

2008-01-0461 Comparison of Powertrain Configuration for Plug-in HEVs from a Fuel Economy Perspective Vincent Freyermuth Argonne National Laboratory Eric Fallas, Aymeric Rousseau Argonne National Laboratory Copyright © 2007 SAE International ABSTRACT With the success of hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) and the still uncertain long-term solution for vehicle transportation, Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEV) appear to be a viable short-term solution and are of increasing interest to car manufacturers. Like HEVs, PHEVs offer two power sources that are able to independently propel the vehicle. They also offer additional electrical energy onboard. In addition to choices about the size of components for PHEVs, choices about powertrain configuration must be made. In this paper, we consider three potential architectures for PHEVs for 10- and 40-mi All Electric Range (AER) and define the components and their respective sizes to meet the same set of performance requirements. The vehicle and component efficiencies in electric-only and charge-sustaining modes will be assessed. INTRODUCTION For the past couple of years, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has invested considerable research and development effort into Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV) technology because of the potential fuel displacement offered by the technology. The PHEV R&D Plan [1], driven by the desire to reduce dependence on foreign oil by diversifying the fuel sources of automobiles, describes the different activities required to achieve the goals. DOE will use Argonne National Laboratory’s (ANL’s) PSAT to guide its analysis activities, stating that “ANL's Powertrain Systems Analysis Toolkit (PSAT) will be used to design and evaluate a series of PHEVs with various 'primary electric' ranges, considering all-electric and charge-depleting strategies.” Argonne designed PSAT [2, 3] to serve as a single tool that can be used to meet the requirements of automotive engineering throughout the development process, from modeling to control. Because of time and cost constraints, designers cannot build and test each of the many possible powertrain configurations for advanced vehicles. PSAT, a forward-looking model, offers the ability to quickly compare several powertrain configurations. When designing a vehicle for a specific application, the goal is to select the powertrain configuration that maximizes the fuel displaced and yet minimizes the sizes of components. In this study, three vehicle powertrain configurations are sized to achieve similar performance for two All Electric Range (AER) approaches. The component sizes and the fuel economy of each option are compared. VEHICLE CONFIGURATIONS Three separate families of powertrain configurations exist for advanced vehicle configurations: 1. Series 2. Parallel 3. Power Split For each option, several hundreds of combinations are possible, including the number of electric machines, their location, and type of transmission. In this study, one configuration from each family was selected. The series engine configuration is often considered to be closer to a pure electric vehicle when compared to a parallel configuration. In this case, the vehicle is propelled solely from the electrical energy. Engine speed is completely decoupled from the wheel axles, and its operation is independent of vehicle operations. As a result, the engine can be operated consistently in a very high efficiency area. The configuration selected includes a single gear ratio before the transmission, which is a configuration similar to that in the GM Volt [4]. In a parallel configuration, both the electric machine and the engine can be used to directly propel the vehicle. The configuration selected is a pre-transmission parallel hybrid, which is similar to the one used by DaimlerChrysler for the PHEV Sprinter [5]. The electric machine is located in between the clutch and the multigear transmission. The power split configuration uses a planetary gear set to transmit power from the engine to the wheel axles, which is a configuration similar to that used in the Toyota Prius [6]. The power split system is the most commonly used system in currently available hybrid vehicles. The split system allows the engine speed to be decoupled (to some extent) from vehicle speed. On one hand, the power from the engine can flow mechanically to the wheel axle via the ring of the planetary system. On the other hand, the engine power can also flow through the generator, producing electricity that will feed the motor to propel the wheels. Hence, the power split system allows both “parallel like” and “series engine like” operations to be combined. engine to remain off throughout the cycle, regardless of the torque request from the driver. Vehicle mass is calculated by adding the mass of each component to the mass of the glider. The mass of each component is defined on the basis of its specific power density. To maintain an acceptable battery voltage (around 200 V), the algorithm will change the battery capacity rather than the number of cells to meet the AER requirements. To do so, a scaling algorithm [7] has been developed to properly design the battery for each specific application. Vehicle Assumptions Motor Power VEHICLE DESCRIPTION AND COMPONENT SIZING Battery Power The selected vehicle class represents a midsize sedan. The main characteristics are defined in Table 1. Table 1: Main Vehicle Characteristics Glider mass Frontal area Coefficient of drag Wheel radius Tire rolling resistance 990 kg 2 2.1 m 0.29 0.317 m 0.008 The components of the different vehicles were sized to meet the following vehicle performance standards: • • • 0–60 mph < 9 s Gradeability of 6% at 65 mph Maximum speed > 100 mph To quickly size the component models of the powertrain, an automated sizing process was developed. A flow chart illustrating the sizing process logic is shown in Figure 1. Although engine power is the only variable for conventional vehicles, PHEVs have two variables: engine power and electric power. In our case, the engine is sized to meet the gradeability requirements. To meet the AER requirements, the battery power is sized to follow the Urban Driving Dynamometer Schedule (UDDS) driving cycle while in all-electric mode. We also ensure that the vehicle can capture the entire energy from regenerative braking during decelerations on the UDDS. Finally, battery energy is sized to achieve the required AER of the vehicle. The AER is defined as the distance the vehicle can travel on the UDDS until the first engine start. Note that a specific control algorithm is used to simulate the AER. This algorithm forces the Engine Power Battery Energy No Convergence Yes Figure 1: Process for Sizing PHEV Components The main characteristics of the sized vehicles are described in Tables 2 and 3. Note that engine power is similar for the parallel and power split configurations and significantly higher for the series configuration. This difference is explained by the inefficiencies associated with the additional components (both generator and electric machine) included in the series configuration. Because the electric machine is the only component used in the series to propel the vehicle, its power is also significantly higher than that in the other configurations. However, because no multi-gear transmission is considered and the component-specific powers represent 2015 technologies, the overall difference in vehicle mass among all of the configurations is minimal. Note that while the series configuration is heavier for the 10-mi (16-km) AER case, the power-split configuration offers the largest mass for the 40-mi (64-km) AER case. Finally, the PHEV will operate in electric-only mode at higher vehicle speed in comparison with regular hybrids. The architecture therefore needs to be able to start the Table 2: Component Size – 10-mi AER case Battery capacity (A•h) Total vehicle mass (kg) Split 74 Series 109 48 62 90 NA 63 106 58 52 55 18 21 18 1675 1667 1700 Pretrans parallel 79 Split 77 Series 114 50 71 95 NA 65 111 61 64 58 71 69 71 1764 1800 1794 VEHICLE CONTROL STRATEGY ALGORITHMS PHEV vehicle operations can be divided into two modes, as shown in Figure 2: • Charge Sustaining (CS) 90 30 Pretrans parallel 76 Table 3: Component Size – 40 mi AER case Parameter Engine power (kW) Propulsion motor power (kW) Generator power (kW) Battery power (kW) Battery capacity (A•h) Total vehicle mass (kg) Charge Depleting (CD) Charge depleting (CD): When the battery state of charge (SOC) is high, the vehicle operates under a so-called blended strategy. Both battery and engine can be used. Engine use increases as SOC decreases. The engine tends to be used in heavy acceleration as well, even though the SOC is high. For fuel economy purposes, this blended strategy is defined for a battery going from full charge to a self- Distance Figure 2: Control Strategy SOC Behavior SERIES CONFIGURATION - Because the engine is completely decoupled from the vehicle operation, numerous control strategies can be chosen. In this study, the engine “on” logic is based on battery SOC. As shown in Figure 3, the engine turns ON when a lower SOC limit is reached (e.g., 0.25) and will stay on until the battery gets recharged to its high limit (e.g., 0.3) if the power request remains positive. If a braking event occurs, the engine is allowed to shut down and will restart when the lower SOC limit is reached again. When the engine is ON, it operates close to its best efficiency point, unless a component saturates (for instance, the battery could reach its maximum charging capability). SOC behavior over a UDDS - 10AER series case SOC (normalized behavior) in % and engine on flag Parameter Engine power (kW) Propulsion motor power (kW) Generator power (kW) Battery power (kW) • sustained SOC, which is typically from 90% to 30% SOC. Charge sustaining (CS): Once the battery is down to 30%, the vehicle operates in CS mode, which is similar to a regular hybrid vehicle. SOC (%) engine at high vehicle speed. In the series configuration (where the engine is completely decoupled from the vehicle speed) and in the parallel configuration (where the engine can be decoupled via the clutch), starting the engine is not an issue. In the power split configuration, the generator is used to start the engine. Because all of those elements are linked to the wheels via the planetary gear system, one needs to make sure that the generator (the speed of which increases linearly with vehicle speed when the engine is off) still has enough available torque — even at high speed — to start the engine in a timely fashion. Engine ON Battery SOC 0.3 0.25 0.2 0 50 100 150 Time (s) 200 250 300 Figure 3: Series Engine SOC Behavior PARALLEL AND POWER SPLIT CONFIGURATIONS The vehicle control philosophies behind both of those configurations are similar. The first critical part of the control strategy logic is related to the engine ON/OFF logic. As Figure 4 shows, the engine ON logic is based on three main parameters: 1. The requested power is above a threshold. 2. The battery SOC is lower than a threshold. 3. The electric motor cannot provide the requested wheel torque. In addition to these parameters, further logic is included to ensure proper drive quality by maintaining the engine ON or OFF for a certain duration. To avoid unintended engine ON events resulting from spikes in power demand, the requested power has to be above the threshold for a predefined duration. The engine OFF logic condition is similar to that of the engine ON condition. Both power thresholds used to start or turn off the engine and to determine the minimum duration of each event have been selected as input parameters of the optimization problem. To regulate the battery SOC, especially during the CD mode, the power demand that is used to determine the engine ON/OFF logic is the sum of the requested power at the wheel plus additional power that depends on battery SOC. This power can be positive or negative, depending on the value of the current SOC compared to the target. Figure 6: SOC Comparison between Each Configuration on UDDS – PHEV 10 Case Figure 4: Simplified Engine ON/OFF Logic Figure 5 shows the different parameters used to define the additional power to regulate the SOC in greater detail. The SOC target has been set when the vehicle is considered entering the charge-sustaining mode (30% SOC). The parameters “ess_percent_pwr_discharged” and “ess_percent_pwr_charged” are percentages used to control the depleting rate and the CS operating window, respectively. CONTROL COMPARISON - Even if the philosophical control strategy is similar for some powertrain configurations, the implementation varies to take advantage of the vehicle’s properties. Figure 6 shows the evolution of the battery SOC on the UDDS, starting from a charged battery at 90%, for the PHEV 10 vehicles. Note that the series configuration discharges the fastest, followed by the parallel and the configurations. The differences are related phenomena, including component operating vehicle mass, and control parameters. Figure 5: Example of Additional Power to Regulate SOC the battery power-split to several conditions, To compare the different powertrain configurations as fairly as possible, we tried to maintain the consistency of the controls as much as possible. However, note that the results obtained depend on the control choices made. FUEL ECONOMY RESULTS Because several approaches are still considered to calculate the fuel economy of PHEVs, we will use the fuel consumed on 15 successive drive cycles to compare the different configurations. Such long distances ensure that in all cases, the final battery SOC is approximately 30%. Table 4 shows the fuel economy results for each powertrain configuration and AER considered. In addition to the UDDS, the HWFET (Highway Fuel Economy Drive Cycle) was also considered. Table 4: PHEV Fuel Economy Results Pre-trans parallel – 10AER Series – 10AER Split – 10AER Pre-trans parallel – 40AER Series – 40AER Split – 40AER UDDS MPG (L/100 km) HWFET MPG (L/100 km) 53/4.4 51.4/4.57 46.6/5 60.4/3.9 43.4/5.42 50.9/4.62 66.4/3.54 60/3.92 64.6/3.64 78.9/2.98 51.1/4.6 59.1/4 URBAN DRIVING - The split configuration provides the best fuel economy in urban driving. In the 10AER case, the parallel configuration outperforms the series configuration. The higher efficiency of the power transfer from engine to wheels benefits the parallel case. HIGHWAY DRIVING - The split and parallel configurations provide similar best fuel economy in highway driving and both outperform the series configuration. The series configuration suffers from dual power conversion — from mechanical (engine) to electrical (generator) and back to mechanical (electric machine). The parallel configuration performs better under the conditions of urban driving than under the conditions of highway driving because higher driving speeds require lower battery use. Engine efficiency in the parallel case is lower than that in the split case. However, the parallel case does not incur losses due to the power recirculation that occurs in the split case, and these losses tend to be higher as vehicle speed increases. As shown in Table 5, engine efficiency is higher for the series configuration than for the other configurations. In this case, the engine is completely decoupled from the wheel and, therefore, can be operated at its best efficiency point. In the split case, the extra degree of freedom provided by the gearbox enables the engine and vehicle speeds to be decoupled, which allows engine efficiency to remain high. The parallel configuration provides the lowest engine efficiency because engine speed is directly linked to the wheel via the fixed-ratio gearbox. As a consequence, its operation at best engine efficiency is more difficult. Data in Table 5 also show that engine efficiency depends on the driving conditions for the parallel case, unlike the other configurations. The results also demonstrate that the parallel configuration tends to perform better in under highway driving than under city conditions. UDDS % 27.7 34.1 32.6 27.5 34.2 32.5 Parameter Pre-trans parallel – 10AER Series – 10AER Split – 10AER Pre-trans parallel – 40AER Series – 40AER Split – 40AER HWFET % 29.2 34.6 32.9 29 34.3 32.8 Table 6 presents both charge-sustaining fuel economy (referred to as the fuel path) and the electrical consumption during EV mode (referred to as the electrical path). Figure 7 is a graphical representation of the information on the 40 AER vehicles presented in Table 6. The electric-only and CS modes are described in more detail in the following paragraph. Table 6: Electrical versus Fuel Path Electrical Path vs. Fuel Path Pre-trans parallel – 10AER Series – 10AER Split – 10AER Pre-trans parallel – 40AER Series – 40AER Split – 40AER Electrical Consumption (wh/km) Fuel economy Table 5: Engine Average Efficiency Electrical Path UDDS Wh/km Fuel Path – CS UDDS MPG (L/100 km) Fuel Path – CS HWFET MPG / (L/100 km) 134 45.7/5.14 46.9/5 133 42.2/5.57 40.6/5.79 131 43.3/5.43 46.9/5 140 42.9/5.48 45.3/5.2 138 41.3/5.69 39.3/5.98 137 51.0/4.6 45.1/5.2 140 120 parallel 40AER series 40AER split 40AER 100 80 60 40 20 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 Fuel Economy (l/100km) Figure 7: Electrical vs. Fuel Path – 40AER case 6 ELECTRICAL PATH - Electrical path efficiency is practically identical for all three configurations. Table 7 shows an overview of the overall efficiency of the main components for the 40AER case. The 10AER case was not reported here as results and trends are similar to those of the 40AER case. Table 7: Component Average Efficiency on UDDS Parameter Electric Machine (%) Transmission (%) Final drive (%) Single gear (%) Battery (%) Pre-trans Parallel 40AER 85.8 94.1 97.5 NA 95 Series 40AER 83.4 NA 97.5 97.5 95 Split 40AER 83.6 96.6 97.5 NA 95 The split and series cases are similar configurations when operated in EV mode. The electric machine is directly linked to the wheels in both cases through a fixed gear and a final drive. Minor spin losses occur in the planetary system, but these losses are not enough to put the split system at a disadvantage when compared to the series configuration. The parallel configuration, even though overall efficiency is identical to that of the other cases, shows a different partition of the losses. Transmission efficiency in this configuration is approximately 2% lower than that in the power split configuration. However, because of the presence of the transmission between the electric machine and the final drive, the electric machine can be operated more efficiently than the series or power split configurations, as shown in Figures 8 and 9. The electric machine efficiency in this case is approximately 2% higher than that in the split case, cancelling out the extra losses occurring in the transmission. Figure 9: Electric Machine Operating Conditions on Parallel 10AER – Density = f (time) FUEL PATH - From highest to lowest, fuel economy in the CS mode is as follows: power split, parallel, and series. Engine fuel consumption maps are proportional to maximum engine power. Power split and parallel configurations have similar engine sizes. The series configuration requires a significantly bigger engine to meet the performance requirement. The series is therefore at a disadvantage from the start. In addition, the power goes through two electric machines, increasing the amount of losses and, hence, the power required by the engine. This impacts the series configuration even more in highway driving. The parallel configuration suffers from the losses in the transmission and its inability to operate the engine at its best operating point, as shown in Figure 10. This configuration is also not capable of regenerating all of the braking energy from the wheels during downshifting events. Figure 10: Engine Operating Conditions on Parallel 10AER – Density = f (time) Figure 8: Electric Machine Operating Conditions on Series Engine 10AER – Density = f (time) The power split allows the engine to be operated close to its most efficient point without the engine sending all of its power through both electric machines, as shown in Figure 11. High engine efficiency and the ability to send mechanical power directly to the wheel allow this configuration to provide the best CS fuel economy. its behalf, a paid-up nonexclusive, irrevocable worldwide license in said article to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the Government. REFERENCES Figure 11: Engine Operating Conditions on Power Split 10AER – Density = f (time) CONCLUSIONS Hybrid vehicles offer a compromise between conventional and purely electric vehicles. Depending on the degree of hybridization, hybrids become more or less close to one of the two extremes. Several powertrain configurations, including series, pre-transmission parallel, and power split, were compared with respect to component sizes and fuel economy for PHEV applications. Although both the power split and series configurations require two electric machines and an engine, the series configuration, as expected, requires significantly higher component power as a result of the many component efficiencies between the engine and the wheel. In terms of efficiency, all of the configurations achieve similar characteristics when operated in electric mode. Both series and power split configurations do not use a multi-gear transmission, but the parallel configuration makes up for losses by operating the electric machine at higher efficiency points. In CD mode, the power split provides the best fuel economy as a result of its dual path of power from the engine to the wheel. On the basis of the thermal and electrical consumption analysis, series configurations appear to be an appropriate choice for vehicles designed to provide long AER because of their simplicity in terms of control and their ability to operate in electric-only mode at high vehicle speed. The power-split configurations appear to be a valid choice for vehicles based on a CD approach. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was supported by DOE’s FreedomCAR and Vehicle Technology Office under the direction of Lee Slezak. The submitted manuscript has been created by UChicago Argonne, LLC, Operator of Argonne National Laboratory (“Argonne”). Argonne, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, is operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The U.S. Government retains for itself, and others acting on 1. U.S. DOE Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle R&D Plan, http://www1.eere.energy.gov/vehiclesandfuels/pdfs/ program/phev_rd_plan_02-28-07.pdf 2. Argonne National Laboratory, PSAT (Powertrain Systems Analysis Toolkit), http://www.transportation. anl.gov/. 3. Rousseau, A.; Sharer, P.; and Besnier, F., “Feasibility of Reusable Vehicle Modeling: Application to Hybrid Vehicles,” SAE paper 2004-011618, SAE World Congress, Detroit, March 2004. 4. General Motors Corporation, http://www.gm-volt.com 5. Graham, B., “Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle, A Market Transformation Challenge: the DaimlerChrysler/EPRI Sprinter Van PHEV Program,” EVS21, April 2005. 6. Rousseau, A.; Sharer, P.; Pagerit, S.; and Duoba, M., “Integrating Data, Performing Quality Assurance, and Validating the Vehicle Model for the 2004 Prius Using PSAT,” SAE paper 2006-01-0667, SAE World Congress, Detroit, April 2006. 7. Sharer, P.; Rousseau, A.; Pagerit, S.; and Nelson, P., “Midsize and SUV Vehicle Simulation Results for Plug-in HEV Component Requirements,” SAE paper 2007-01-0295, SAE World Congress, Detroit, April 2007. 8. Carlson, R., et al., “Testing and Analysis of Three Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles,” SAE paper 200701-0283, SAE World Congress, Detroit, April 2007. CONTACT Aymeric Rousseau Center for Transportation Research (630) 252-7261 arousseau@anl.gov