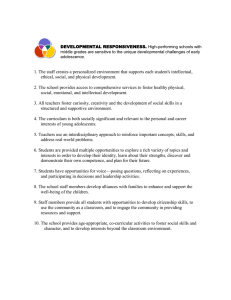

Alternative forms of care for children without adequate family support

advertisement