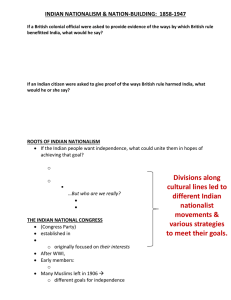

The development of nationalism in the Indian case

advertisement