Strategies to achieve economic and environmental gains

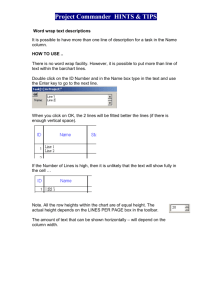

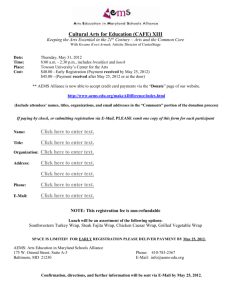

advertisement