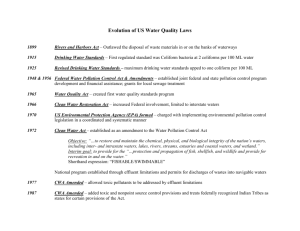

Water Quality Control: A Modern Approach to State

advertisement