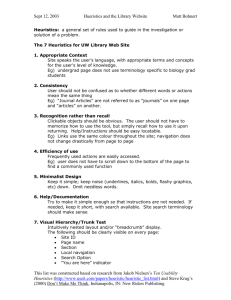

Designing Web Sites for Older Adults: Expert Review of

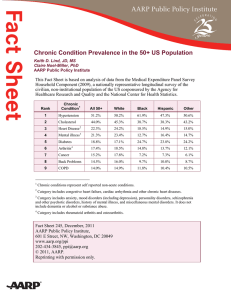

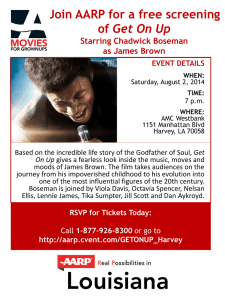

advertisement