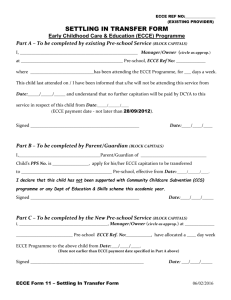

Supporting Access to the Early Childhood Care and Education

advertisement