Mentor Functions and Outcomes: A Comparison of Men and Women

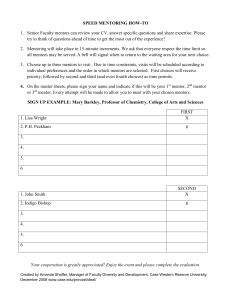

advertisement