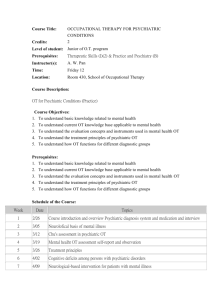

The Vital Role of State Psychiatric Hospitals

advertisement