Take Charge! Tips For Running Meetings Smoothly

advertisement

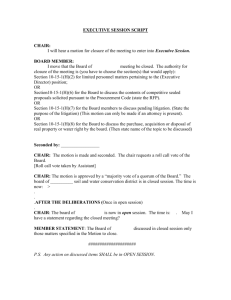

TAKE CHARGE! TIPS FOR RUNNING MEETINGS SMOOTHLY Guidelines for planning and conducting meetings, to help you get the most value from participants. BY KENNETH J. HIRSH 28 AALL SPECTRUM | WWW.AALLNET.ORG C ongratulations! You’ve been elected president of an organization or you’ve been named a committee chair. Perhaps you are a supervisor, and among your duties is running staff meetings. Regardless of the reason, you’ve taken on the responsibility of running a meeting that not only requires your attention and time but also the time of other people, which you wish to respect. Whether you feel anxious or confident about running your next meeting, the following tips to better run your meetings and summary of the rules of parliamentary procedure (i.e., the rules of the road for most meetings) could prove beneficial. Planning Your Meeting All meetings have a primary purpose, understanding that purpose will help you to fulfill it while using everyone’s time as efficiently as possible. Your group might be meeting to gather information, to solicit feedback, to brainstorm, or to make progress toward or reach a decision. Hence, the first step to conducting a successful meeting is to understand its primary purpose. The aims for your meeting should determine several parameters: ¡¡ Who else will participate; keep in mind that every attendee’s time is valuable. ¡¡ The agenda; nearly every meeting should have a written agenda prepared and distributed well enough in advance that attendees can prepare for discussion. The agenda is also your outline to keep the meeting on course and ensure that all relevant and important topics are discussed. ¡¡ The length of the meeting; it should balance the time you need to accomplish its purpose with the availability of the participants. ¡¡ The nature of the participation of the other attendees; are they stakeholders in any decisions to be made or are you merely sharing information with them? Conducting the Meeting Ilmage © iStockPhoto.com. Be on time, start on time. It should go without saying: be on time, or, better yet, be a little early for a meeting you are leading. First, you called the meeting, so it cannot start without you. If you are late, you are showing disregard for the time of the punctual attendees. Second, when you start on time you set a good example for the other attendees, and they learn that you value their time as much as you do your own. Follow the order of your agenda. More formal meetings will require a vote to approve the agenda at the All meetings have a primary purpose, understanding that purpose will help you to fulfill it while using everyone’s time as efficiently as possible. … Hence, the first step to conducting a successful meeting is to understand its primary purpose. opening of the meeting and another vote to make any subsequent changes to the agenda. Informal meetings, such as a regularly scheduled staff meeting, likely do not require such formalities. However, following the agenda will make it clear when your discussion goes off track, and you can then use the agenda to guide everyone back to the issues at hand. Offer ample opportunities for all participants to have their say. Not only does this increase the likelihood of broad buy-in for decisions made at, or as a result of, the meeting but it also encourages participants to share information that you or other decision-makers may not have known. Know when to end discussion. If you teach legal research, you may tell your students that they’ve reached the end of their work when everything they find repeats something they’ve already discovered. Apply this rule to your discussion: when the same voices are repeating points that have already been made, it’s time to call for a vote or otherwise move on. End the meeting on time. If an important matter is under discussion and needs to be resolved before you adjourn, pause to ask the group’s permission to extend the meeting. In a formal meeting with a set adjournment time, you will need to call for a vote to extend the meeting. Recap and follow-up. Before you break up the group, reiterate any decisions reached and any assignments made for follow-up action. Communicate these in writing by the end of the next business day. This reinforces recollections of assignments and offers an opportunity to clarify any misunderstandings of responsibilities. Remote Participation in Meetings IT’S PARLIAMENTARY For more information, readers who wish to formally study parliamentary procedure or even become a professional parliamentarian will find useful information on the website of the American Institute of Parliamentarians at www.aipparl.org. The Standard Code of Parliamentary Procedure and Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised are available from bookstores. Conference calls and other forms of remote participation in meetings present challenges to the meeting leader and all of the participants. Remote participants in a meeting that includes several people at the host site (“mixed attendance meetings”) are at a disadvantage in that they cannot observe the body language of others, may not recognize the voice of the speaker, and may not be able to see who has asked to be recognized. The meeting leader and participants can take a few steps to minimize the confusion that might otherwise ensue: ¡¡ During an apparent pause, remote participants should audibly ask for recognition and wait for permission before continuing to speak. NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015 | AALL SPECTRUM 29 Legal information professionals do not hesitate to refer to statutes, regulations, and cases to help their clients and students understand the applicable law in a given situation. Surprisingly, it is not unusual that they are unfamiliar with the more common rulebooks for governing meetings. ¡¡ The chair should announce the names of those who are in the speaking queue. ¡¡ Every speaker should identify himself or herself aloud before making substantive remarks. At a meeting when all participants are remotely participating, the relative disadvantage of each is reduced, but the above tips will help facilitate efficient and civil discussion. Rules for Conduct of Meetings All but the most informal meetings need rules to ensure fair and efficient proceedings. Legal information professionals do not hesitate to refer to statutes, regulations, and cases to help their clients and students understand the applicable law in a given situation. Surprisingly, it is not unusual to find that many are unfamiliar with the more common rulebooks for governing the meetings that they attend. In the United States, the two most commonly used rules handbooks are Robert’s Rules of Order and the American Institute of Parliamentarians Standard Code of Parliamentary Procedure. The former was first published by then U.S. Army Major (and later Brigadier General) Henry M. Robert in 1876, and the latter was first published in 1950 by Alice Sturgis, whose surname was part of the title through several editions until the latest revision in 2012. Many still informally refer to the volume as “Sturgis.” Robert adapted the rules used by the U.S. House of Representatives (which were largely taken from Thomas Jefferson’s A Manual of Parliamentary Practice) to be more useful to “ordinary societies” rather 30 AALL SPECTRUM | WWW.AALLNET.ORG than legislative bodies. It has been revised several times, with the most recent edition published in 2011 as Robert’s Rules of Order Newly Revised. Alice Sturgis wrote her Standard Code to simplify rules and remove archaic language. She preserved fundamental principles of procedure while trying to make the rules easier to understand. The American Association of Law Libraries (AALL) used Robert’s Rules until 1996, when the membership approved a change to the organization’s constitution to make the Standard Code the governing authority for AALL meetings. The rules discussed below are as provided in the Standard Code. The handbook sets out several fundamental principles of parliamentary procedure, and it is useful to keep these in mind when running a meeting. Among them are equality of rights, majority vote decides, minority rights of participation are protected, the right of discussion, the right to information, and all actions should be taken in fairness and good faith. Just as nature abhors a vacuum, discussion at a business meeting should begin with a proposal to do something. A member makes that proposal by first seeking to be recognized (i.e., called upon by the chair) and, once having been “given the floor,” states “I move that …” followed by the detailed action to be taken. In a large meeting the member will stand to be heard; this is called “rising to speak.” Following the movant’s making the motion, the chair repeats the language of the motion in the form, “It has been moved that …” and calls for a second of the motion. If there is a second by another member, the chair notes that and opens discussion of the motion. If there is no second, the motion dies for lack of a second. There is one instance when a second to a motion is not required: when a committee of the membership is proposing action in its report. It is assumed that a majority of committee members voted in favor of its report, and hence it is assumed that the report already carries the support of two or more members. Therefore, once any member moves the adoption of a committee report or recommendation, the chair opens discussion. The requirement that a motion be “on the floor” before starting discussion ensures more efficient use of time and promotes clarity, but there are times when informal discussion of ideas may ultimately be beneficial. In such cases, a member may move for informal discussion of a topic without proposing a specific action, and, upon second and passage, the meeting may conduct a more informal but still courteous discussion. Informal discussion is brought to its end by either a motion to take some action resulting from the points made in the discussion or, in the absence of such a motion, to end the informal discussion. Once a motion is on the floor, the chair should call in order on those who seek to be recognized by raising their hands. Typically the chair first calls upon the movant to expand on the motion and to explain its rationale. If the chair is aware of the sides that particular members have taken on the issue, then he or she may alternate calling on speakers for each side. The chair should ensure that all who wish to speak are given the opportunity to do so. At a point when there remains no one who wishes to speak, the chair asks if the group is ready to vote. If no one expresses disagreement, the chair will call the vote, first by those who vote in the affirmative with “yea” or “yes,” and then by those who vote in the negative with “nay” or “no.” If some members still wish to continue speaking when the chair or other members believe that fruitful discussion has concluded, then a member summarizes the various motions and gives their relative rank, whether they are debatable and amendable, and whether a two-thirds vote is required for passage. Several versions of similar tables are available online, including one from UC San Diego found at cseweb.ucsd.edu/~ddahlstr/ misc/roberts/parlia_sturgis.pdf. Another principle to note is that additional rules, such as those setting limits on meeting time or debate, may be adopted by majority rule at the outset of the meeting, but subsequently changing the limits on debate or the meeting time will require a two-thirds vote. An individual who is trained in applying the rules of parliamentary procedure is called, of course, a “parliamentarian.” If you have attended an AALL Annual Business Meeting, you may have noticed that there is a professional parliamentarian present to advise the president on applying the rules when a question of procedure arises. It is the president’s own authority that implements the professional advice given by the parliamentarian through a “ruling by the chair.” As provided by the rules themselves, a ruling by the chair may be appealed to the membership by motion and second. A majority vote is required to overturn the ruling. ¢ KENNETH J. HIRSH DIRECTOR OF THE LAW LIBRARY AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND PROFESSOR OF PRACTICE University of Cincinnati College of Law Cincinnati, Ohio ken.hirsh@uc.edu © KENNETH J. HIRSH, 2015 may rise to move to close debate. Following a second, the chair immediately puts this motion to a vote, and if a two-thirds majority approves, the chair then calls the vote on the main motion. If the motion to close debate fails, then discussion of the main motion continues. As discussed earlier, the motion first made to take some action is called “the main motion.” A main motion, in addition to being subject to discussion following its seconding, is subject to the introduction of subsidiary, privileged, and incidental motions. One example of a subsidiary motion is a motion to amend. Such a motion is in order while the main motion is being debated. The rules spell out in detail which motions may properly be made or “are in order” when a given motion is on the floor. The inside cover pages of the Standard Code include a table that Ken is a strictly amateur parliamentarian. SAVE THE DATE | JULY 16-19, 2016 FIND YOUR INSPIRATION JOIN US IN CHICAGO, THE CITY OF INNOVATION for the 109TH AALL ANNUAL MEETING & CONFERENCE I N N O V A T E D I N C H I C A G O FERRIS WHEEL[1893] [1937] FIRST U.S. BLOOD BANK REVERSING THE CHICAGO RIVER WIRELESS REMOTE CONTROL[1955] FIRST GAY RIGHTS GROUP IN THE U.S.[1924] BIRTH CONTROL PILL THE ZIPPER [1900] [1893] [1960] SKYSCRAPER[1884] OPEN-HEART SURGERY CELL PHONE[1973] [1893] Read more at bit.ly/Chi25Innovations Challenge. Create. Inspire. www.aallnet.org/conference NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015 | AALL SPECTRUM 31