THE FINNISH SUCCESS IN PISA – AND SOME REASONS BEHIND IT

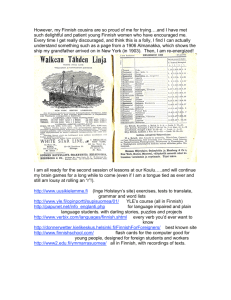

advertisement