The ATA Directive

advertisement

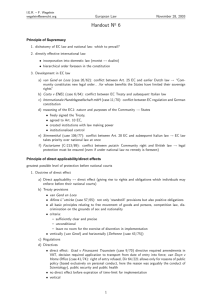

The ATA Directive The EU participated in the OECD’s BEPS project and during the course of 2015 it became clear that some effort would be made at EU level to coordinate the response of Member States to the BEPS recommendations. In December 2015, the Council of the EU (the “Council”) invited the Commission to propose a draft directive to tackle BEPS. At the same time, the Council itself issued an early draft ATA Directive. The ATA Directive is only in draft form and we have outlined here what is required before it could become law. The Commission proposal includes the following draft provisions: interest limitation rules – the draft ATA Directive includes provisions to limit the availability of interest deductions in line with the recommendations made by the OECD. Under the current proposal, EU taxpayers will be permitted on an annual basis to deduct net interest expenses not exceeding 30% of EBITDA or €1 million, whichever is higher. Member States will be free to set lower limits. The current draft provides for non-deductible interest expense to be carried forward to future years and for unutilised EBITDA capacity to be carried back to previous tax years or forward. It also permits Member States to include a group carve-out rule in their domestic provisions that will permit deductions in excess of the 30% limit within certain parameters. The general limitation does not apply to certain financial institutions, including, banks, insurers, alternative investment funds and UCITS. It is intended that in time separate provisions will be agreed for such taxpayers. exit tax provisions – the exit tax provisions will require EU Member States to levy tax on: (a) the ‘transfer’ of assets by a company to its permanent establishment (“PE”) in another jurisdiction; (b) the ‘transfer’ of assets from a company’s PE to its head office; (c) migration of tax residence of a company to another jurisdiction; and (d) the transfer of a business carried on in a Member State by a PE to another jurisdiction. It is proposed that the exit tax will apply even if there has been no realisation of the latent gain. Member States may permit the due date for payment of the tax to be deferred for up to five years or to be spread over five years where the transfer is to another EU Member State or EEA country. Member States will not be obliged to impose an exit tax if the transfer is temporary and the assets are intended to revert to the Member State of the transferor. a switch-over clause – a so-called ’switch-over’ provision has been included in the draft ATA Directive. Under the terms of the switch-over provision, EU Member States would be precluded from applying exemptions to certain income from non-EU Member States (including distributions, gains arising on the disposal of shares, and branch profits) where the statutory rate applied in that country is lower than 40% of the statutory rate that would have been applied in the Member State receiving the income. Instead of applying the exemption, the receiving EU Member State would be required to tax the income and permit a deduction for foreign tax paid. a general anti-abuse rule (“GAAR”) – under the proposed GAAR, EU Member States would be required to ignore “non-genuine arrangements or a series thereof carried out for the essential purpose of obtaining a tax advantage that defeats the object or purpose of the otherwise applicable tax provisions”. In those circumstances the relevant Member State would be required to determine the tax liability of the relevant taxpayer in accordance with national law. Many EU Member States, including Ireland have pre-existing GAARs. controlled foreign company (“CFC”) rules – the proposed CFC rules will apply primarily in respect of non-EU entities controlled directly or indirectly (whether through voting rights, shareholding or distribution rights) by a taxpayer where the profits of the entity are taxed at an effective rate that is lower than 40% of the effective rate that would have applied in the taxpayer’s jurisdiction. An entity will be treated as a CFC if more than 50% of its income falls within specified categories (interest, royalties, dividends, income from the disposal of shares, financial leasing, immovable property, income from insurance, banking and financial activities and income from services provided to associated entities). Entities that might otherwise be treated as CFCs of banks, insurers, alternative investment funds and certain other financial institutions will only be considered as such if more than 50% of their income in the specified categories comes from associated entities. In a provision that appears to be derived from the Cadbury Schweppes decision, an entity that is tax resident in another EU Member State or EEA country may only be treated as a CFC if “the establishment of the entity is wholly artificial or to the extent that the entity engages, in the course of its activity, in non-genuine arrangements which have been put in place for the essential purpose of obtaining a tax advantage.” There is likely to be some overlap between the entities to which the switch-over provisions apply and those to which the CFC provisions apply. Whether both provisions are required was discussed at Council level and may be open to further discussion. anti-hybrid provisions – the anti-hybrid provisions included in the draft ATA Directive are designed to neutralise the effect of hybrid mismatches arising between Member States only. In simple terms, the provisions require Member States to adopt a common approach to the classification of entities and instruments in circumstances where a mismatch arises. The classification of the entity or instrument in the source Member State shall be the classification that is applied by both Member States. The approach to hybrid entities proposed in the draft ATA Directive is different to the approach adopted by the OECD under BEPS Action 2. This may cause some headaches for those EU Member States that have already started to revise their domestic rules to take account of the recommendations made under BEPS Action 2 (notably, the UK). Next steps It is difficult at this stage to predict by when the ATA Directive will be finalised (or if it can be). No proposed implementation date has been included in the draft released. A number of outcomes, including the following, are possible: the ATA Directive could be agreed unanimously in its current form (or something very close to its current form); the fate of the ATA Directive could be similar to that of previous EU legislative proposals on direct tax – some Member States (or even just one Member State) might consider that the proposal is entirely unacceptable and vote against it and all iterations of it. In those circumstances some Member States may wish to progress the ATA Directive (in some form) under the enhanced cooperation procedure; if Member States struggle to agree the ATA Directive in its existing form, the more controversial provisions may be dropped and the Commission may seek to agree a ‘slimmed down’ version of the ATA Directive including only the consensus items (whatever they might be). It is clear from the announcements made yesterday that that the Commission considers that a coordinated approach to cross-border tax is essential. However, historically direct tax has been viewed by Member States as central to national sovereignty. Whether Member States will be more amenable to agreeing the proposals in a post-BEPS environment remains an open question.