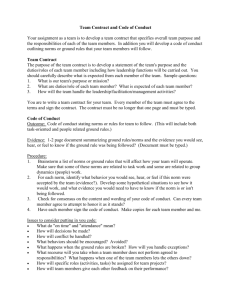

Quality of Decision Making and Group Norms

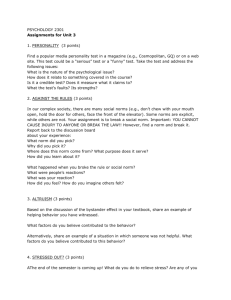

advertisement