Species at Risk Act

Management Plan Series

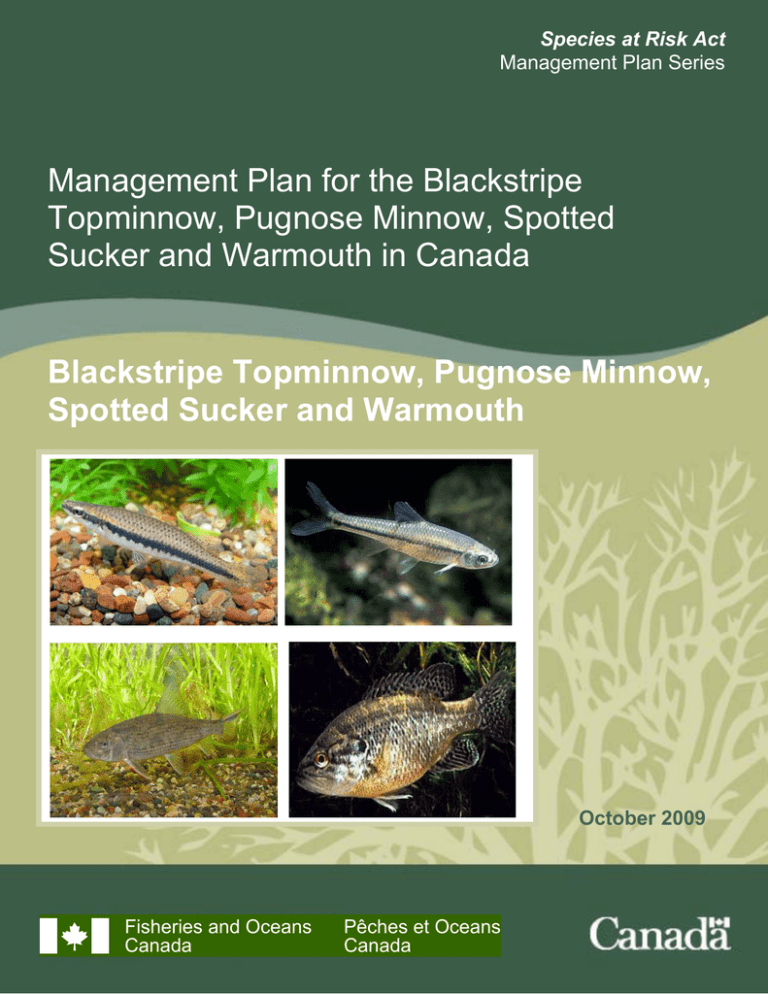

Management Plan for the Blackstripe

Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow, Spotted

Sucker and Warmouth in Canada

Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Fisheries and Oceans

Canada

Pêches et Oceans

Canada

About the Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series

What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)?

SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common

national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003,

and one of its purposes is “to manage species of special concern to prevent them from

becoming endangered or threatened.”

What is a species of special concern?

Under SARA, a species of special concern is a wildlife species that could become threatened or

endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

Species of special concern are included in the SARA List of Wildlife Species at Risk.

What is a management plan?

Under SARA, a management plan is an action-oriented planning document that identifies the

conservation activities and land use measures needed to ensure, at a minimum, that a species

of special concern does not become threatened or endangered. For many species, the ultimate

aim of the management plan will be to alleviate human threats and remove the species from the

List of Wildlife Species at Risk. The plan sets goals and objectives, identifies threats, and

indicates the main areas of activities to be undertaken to address those threats.

Management plan development is mandated under Sections 65–72 of SARA

(http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/approach/act/default_e.cfm).

A management plan has to be developed within three years after the species is added to the

List of Wildlife Species at Risk. A period of five years is allowed for those species that were

initially listed when SARA came into force.

What’s next?

Directions set in the management plan will enable jurisdictions, communities, land users, and

conservationists to implement conservation activities that will have preventative or restorative

benefits. Cost-effective measures to prevent the species from becoming further at risk should

not be postponed for lack of full scientific certainty and may, in fact, result in significant cost

savings in the future.

The series

This series presents the management plans prepared or adopted by the federal government

under SARA. New documents will be added regularly as species get listed and as plans are

updated.

To learn more

To learn more about the Species at Risk Act and conservation initiatives, please consult the

Species at Risk Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca).

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth in Canada

October 2009

Recommended citation:

Edwards, A.L. and S.K. Staton. 2009. Management plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow,

Pugnose Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth in Canada. Species at Risk Act Management

Plan Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. viii + 43 pp.

Additional copies:

Additional copies can be downloaded from the SARA Public Registry

(http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/).

Cover photographs: Clockwise from upper left: Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker, Warmouth. Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow and Spotted Sucker ©

Konrad Schmidt.

Également disponible en français sous le titre

«Plan de gestion pour le fondule rayé, le petit-bec, le meunier tacheté et le crapet sac-à-lait au

Canada [proposition]»

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment,

2009. All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-100-12129-1

Catalogue no. En3-5/5-2009E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to

the source.

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

PREFACE

Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth are freshwater fishes

and are under the responsibility of the federal government. The Minister of Fisheries and

Oceans is a “competent minister” for aquatic species under the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Since Warmouth is located in Point Pelee National Park of Canada administered by the Parks

Canada Agency (Parks Canada), the Minister of the Environment is also a “competent minister”

under SARA for this species only. The Species at Risk Act (SARA, Section 65) requires the

competent ministers to prepare management plans for species listed as special concern. The

Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth were listed as

species of special concern under SARA in 2003. The development of this management plan

was led by Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Central and Arctic Region, in cooperation and

consultation with many individuals, organizations and government agencies, including the

Government of Ontario, the Parks Canada Agency, the University of Windsor and the Upper

Thames Rivers Conservation Authority. The plan meets SARA requirements in terms of content

and process (SARA sections 65-68).

Success in the conservation of these species depends on the commitment and cooperation of

many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this

plan and will not be achieved by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Parks Canada or any other

party alone. This plan provides advice to jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved or

wish to become involved in activities to conserve this species. In the spirit of the Accord for the

Protection of Species at Risk, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans and the Minister of the

Environment invite all responsible jurisdictions and Canadians to join Fisheries and Oceans

Canada and Parks Canada in supporting and implementing this plan for the benefit of the

Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth, and Canadian

society as a whole. The competent ministers will report on progress within five years.

RESPONSIBLE JURISDICTIONS

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Government of Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

AUTHORS

This document was prepared by Amy L. Edwards and Shawn K. Staton on behalf of Fisheries

and Oceans Canada and Parks Canada.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Fisheries and Oceans Canada would like to thank the following organizations for their support in

the development of this management plan: the Ontario Freshwater Fish Recovery Team, Parks

Canada Agency, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Ministry of the Environment,

i

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

University of Windsor and the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority. Mapping was

produced by Carolyn Bakelaar (DFO).

ii

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning

documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of

Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. The purpose of a SEA is to incorporate environmental

considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support

environmentally-sound decision making.

Management planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general.

However, it is recognized that plans may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects

beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly

incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible

impacts on non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into

the plan itself, but are also summarized below.

This management plan will clearly benefit the environment by promoting the conservation of the

Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth. The potential for the

plan to inadvertently lead to adverse effects on other species was considered. The SEA

concluded that this plan will clearly benefit the environment and will not entail any significant

adverse effects. The reader should refer to the following sections of the document in particular:

description of the species’ habitat and biological needs, ecological role, and limiting factors;

effects on other species; and, the management implementation actions.

iii

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In Canada, the Blackstripe Topminnow (Fundulus notatus), Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus

emiliae), Spotted Sucker (Minytrema melanops) and Warmouth (Lepomis gulosus) all occur in

southwestern Ontario. The Blackstripe Topminnow is found only in the Sydenham River and

Lake St. Clair drainages and the Warmouth is found only in four areas of Lake Erie (Long Point

Bay, Big Creek National Wildlife Area [Long Point region], Rondeau Bay and Point Pelee

National Park). The Pugnose Minnow and Spotted Sucker are found in Lake St. Clair and its

smaller tributaries, Lake Erie, the Detroit River, the Sydenham River and the Thames River. In

addition, the Spotted Sucker is also found in the St. Clair River.

All four species are listed as Special Concern and are on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at

Risk Act. As such, the Act requires that management plans be developed that identify

management approaches for each species. Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Parks

Canada Agency, in cooperation with the government of Ontario, have developed a single

management plan to aid in the conservation and management of these four species. In

recognition of the degree of overlap between these species in their distribution, as well as the

commonality of threats, a multi-species approach was adopted for the management of these

species.

Little data are available regarding population sizes and trends, biology or ecology of these four

species. All face similar known and suspected threats, which include: habitat loss and

degradation; sediment and nutrient loading; toxic compounds; exotic species; altered coastal

processes; climate change; incidental harvest; and, barriers to movement.

This management plan defines the goal, objectives and recommended approaches believed to

be necessary for the conservation and management of these four species in Canada.

The long-term goal of this management plan is to maintain, or enhance, existing populations of

the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth in Canada, and

to improve the quality and quantity of their associated habitats. This will be accomplished

primarily through the implementation of ecosystem recovery/management approaches, in

cooperation with relevant single/multi-species and ecosystem-based recovery programs, to

mitigate identified threats.

The following short-term objectives (over the next 5-10 years) have been identified to assist in

achieving the management goal:

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

v.

vi.

To understand the health and extent of existing populations;

To improve our knowledge of the species’ biology, ecology and habitat requirements;

To understand trends in populations and habitat;

To maintain and improve existing populations;

To ensure the efficient use of resources in the management of these species; and,

To improve awareness of these species and engage the public in conservation of these

species.

Some measures have already been implemented for the management of these species. In

Ontario, three ecosystem-based recovery strategies address two or more of the species (EssexErie region, Sydenham River, Thames River). Stewardship and awareness initiatives have

been developed by the ecosystem-based recovery teams and are ongoing throughout the

iv

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

species’ ranges. The development and implementation of management actions is being

coordinated with species at risk recovery teams throughout the species’ ranges to facilitate

information sharing. Coordination with other recovery teams will help to ensure that proposed

management actions do not negatively impact upon other co-occurring species at risk;

management actions may, in fact, enhance or facilitate recovery of other species at risk.

v

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ I

RESPONSIBLE JURISDICTIONS ................................................................................... I

AUTHORS........................................................................................................................ I

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................................................................... I

STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ......................................................... III

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................IV

INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1

1.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – BLACKSTRIPE TOPMINNOW................................ 2

1.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC............................................ 2

1.2

Description ........................................................................................................ 2

1.3

Populations and Distribution ............................................................................. 2

1.4

Needs of the Blackstripe Topminnow................................................................ 5

1.4.1

Habitat and biological needs...................................................................... 5

1.4.2

Ecological role ........................................................................................... 6

1.4.3

Limiting factors........................................................................................... 6

2.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – PUGNOSE MINNOW.............................................. 7

2.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC............................................ 7

2.2

Description ........................................................................................................ 7

2.3

Populations and Distribution ............................................................................. 8

2.4

Needs of the Pugnose Minnow ....................................................................... 11

2.4.1

Habitat and biological needs.................................................................... 11

2.4.2

Ecological role ......................................................................................... 12

2.4.3

Limiting factors......................................................................................... 12

3.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – SPOTTED SUCKER ............................................. 13

3.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC.......................................... 13

3.2

Description ...................................................................................................... 13

3.3

Populations and Distribution ........................................................................... 14

3.4

Needs of the Spotted Sucker .......................................................................... 17

3.4.1

Habitat and biological needs.................................................................... 17

3.4.2

Ecological role ......................................................................................... 17

3.4.3

Limiting factors......................................................................................... 17

4.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – WARMOUTH ........................................................ 18

4.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC.......................................... 18

4.2

Description ...................................................................................................... 18

4.3

Populations and Distribution ........................................................................... 19

4.4

Needs of the Warmouth .................................................................................. 22

4.4.1

Habitat and biological needs.................................................................... 22

4.4.2

Ecological role ......................................................................................... 22

4.4.3

Limiting factors......................................................................................... 22

5.0

THREATS........................................................................................................... 22

5.1

Threat classification ........................................................................................ 23

5.2

Description of threats ...................................................................................... 25

5.2.1

Habitat Loss and Degradation ................................................................. 25

5.2.2

Sediment Loading.................................................................................... 25

vi

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

5.2.3

Nutrient Loading ...................................................................................... 25

5.2.4

Exotic Species ......................................................................................... 25

5.2.5

Altered Coastal Processes....................................................................... 26

5.2.6

Climate Change ....................................................................................... 26

5.2.7

Toxic Compounds .................................................................................... 27

5.2.8

Incidental Harvest .................................................................................... 27

5.2.9

Barriers to Movement............................................................................... 27

5.2.10 Changes to Trophic Dynamics................................................................. 28

5.3

Actions Already Completed or Underway ....................................................... 28

5.4

Knowledge Gaps............................................................................................. 31

6.0

MANAGEMENT.................................................................................................. 32

6.1

Goal ................................................................................................................ 32

6.2

Objectives ....................................................................................................... 32

6.3

Actions ............................................................................................................ 32

6.3.1

Background surveys ................................................................................ 32

6.3.2

Monitoring ................................................................................................ 33

6.3.3

Research ................................................................................................. 34

6.3.4

Coordination with recovery teams and other complimentary initiatives.... 35

6.3.5

Outreach and communication .................................................................. 35

6.3.6

Stewardship and habitat improvement (threat mitigation) ........................ 35

6.4

Effects on Other Species ................................................................................ 35

7.0

IMPLEMENTATION SCHEDULE ....................................................................... 36

8.0

ASSOCIATED PLANS........................................................................................ 37

9.0

REFERENCES ................................................................................................... 37

10.0 CONTACTS........................................................................................................ 42

APPENDIX 1. RECORD OF COOPERATION AND CONSULTATION......................... 43

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Blackstripe Topminnow

(NatureServe 2008)...............................................................................................................5

Table 2. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Pugnose Minnow (NatureServe

2008). ..................................................................................................................................11

Table 3. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Spotted Sucker (NatureServe

2008). ..................................................................................................................................16

Table 4. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Warmouth (NatureServe 2008).

............................................................................................................................................21

Table 5. Threat classification table .............................................................................................24

Table 6. Existing ecosystem-based recovery strategies that include two or more of the four

Special Concern species.....................................................................................................29

Table 7. Summary of recent fish surveys throughout the range of the Blackstripe Topminnow,

Pugnose Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth. ............................................................31

Table 8. Implementation schedule. .............................................................................................36

vii

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Blackstripe Topminnow (Fundulus notatus, male). ........................................................2

Figure 2. North American distribution of the Blackstripe Topminnow ...........................................3

Figure 3. Canadian distribution of the Blackstripe Topminnow....................................................4

Figure 4. Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus emiliae). ....................................................................7

Figure 5. North American distribution of the Pugnose Minnow .....................................................8

(Cudmore and Holm 2000). ..........................................................................................................8

Figure 6. Canadian distribution of the Pugnose Minnow. ...........................................................10

Figure 7. Spotted Sucker (Minytrema melanops; male)..............................................................13

Figure 8. Global range of the Spotted Sucker (COSEWIC 2005a). ............................................14

Figure 9. Canadian range of the Spotted Sucker........................................................................15

Figure 10. Warmouth (Lepomis gulosus)....................................................................................18

Figure 11. Global distribution of Warmouth (COSEWIC 2005b). ................................................19

Figure 12. Canadian distribution of the Warmouth. ....................................................................20

Figure 13. Location of watershed-based species at risk recovery programs ..............................29

viii

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

INTRODUCTION

The watersheds of southern Ontario support some of the richest communities of fishes in the

country. More than half of the 230 species of fishes known to exist in Canada are found in the

region. A high proportion of Canada’s fish species at risk are also found in southwestern

Ontario and 34 species have been assigned a conservation status (OMNR 2006). Staton and

Mandrak (2006) identified priority watersheds for protecting freshwater species at risk in

Canada, which included ‘conservation hot spots’ within Carolinian Canada watersheds of

southwestern Ontario.

The Ontario Freshwater Fish Recovery Team (OFFRT) was formed to address the recovery

planning obligations for freshwater fishes listed under Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA).

The national management plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow, Spotted

Sucker and Warmouth was developed by the OFFRT using the best available information in an

effort to conserve the species and reduce the threats to their populations. These four species

are at the northern extent of their ranges and all have been impacted, to some extent, by habitat

degradation. They have all been listed as Special Concern under SARA. In recognition of the

degree of overlap between these species in their distribution, as well as the commonality of

threats, the OFFRT has adopted a multi-species approach to the management of these species.

1

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

1.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – BLACKSTRIPE TOPMINNOW

1.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC

October 2009

Date of Assessment: May 2001

Common Name (population): Blackstripe Topminnow

Scientific Name: Fundulus notatus (Rafinesque, 1820)

COSEWIC Status: Special Concern

Reason for Designation: This species has a limited distribution in southwestern Ontario where

it is impacted by habitat degradation and loss from industrial, urban and agricultural

development.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Special Concern in April 1985. Status re-examined and

confirmed in May 2001. Last assessment based on an update status report.

1.2

Description

The following description has been adapted from Mandrak and Holm (2001). The Blackstripe

Topminnow (Fundulus notatus Rafinesque, 1820) (Figure 1) is a small fish with a maximum total

length (TL) of 74 mm. This species has a protractile upper jaw (adapted for feeding at the

water’s surface), partially scaled head, spineless fins, rounded caudal fin, single dorsal fin at or

behind the middle of the body, flattened area anterior to the dorsal fin and abdominal pelvic fins.

It can be distinguished from the banded killifish (F. diaphanus) and mummichog (F. heteroclitus)

by the prominent black lateral stripe and the origin of the dorsal fin behind the origin of the anal

fin. Male Blackstripe Topminnow have crossbars on the lateral stripe, a deepened body, and

elongated dorsal and anal fins that are bright yellow in colour. Females lack crossbars on the

lateral stripe, have white fins, rounded dorsal and anal fins, and a distinctly fleshy sheath at the

origin of the anal fin.

Figure 1. Blackstripe Topminnow (Fundulus notatus, male). © Joseph R. Tomelleri (1998).

1.3

Populations and Distribution

Distribution:

Global Range (Figure 2): The Blackstripe Topminnow is found in lowland areas of the southern

Great Lakes drainages (lakes Erie and Michigan), in the Mississippi basin from Illinois to the

Gulf of Mexico, and along the lower coastal plain from Texas to Alabama. It occurs in 16 states

and southern Ontario (Mandrak and Holm 2001).

2

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Figure 2. North American distribution of the Blackstripe Topminnow. Adapted from Page

and Burr (1991) and Shute (1980).

Canadian Range (Figure 3): The Canadian range of the Blackstripe Topminnow is primarily

restricted to an area of approximately 60 km² in the Sydenham River watershed where it is

found in the North Sydenham River basin (including Bear, Black, Booth, Crooked, East Otter,

Fox, Ryan’s and West Otter creeks) as well as the lower East Sydenham River, including

Molly’s Creek (Mandrak and Holm 2001, Dextrase et al. 2003). It was also recently found in

Little Bear Creek, Maxwell Creek and Whitebread Drain (Lake St. Clair drainage; Mandrak et al.

2006).

3

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Figure 3. Canadian distribution of the Blackstripe Topminnow.

4

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Percent of Global Distribution in Canada: Less than 5% of the species’ global distribution is

currently found in Canada.

Population Size and Status:

Global Population Size and Status: Although there are no population estimates for the

Blackstripe Topminnow in the United States, it is possible to make inferences from available

information. This species is common to abundant in most parts of its range in the United States,

and has expanded its range in some areas. In Ohio, recent surveys indicate a range expansion

in the Portage River basin, and in Wisconsin, populations have expanded in the last 50 years,

despite inhabiting heavily disturbed waters (Becker 1983, Mandrak and Holm 2001). The

species is ranked as secure (N5) in the United States, imperilled (S2/S3) in Michigan, and

vulnerable (S3) in Alabama and Iowa (NatureServe 2008). Complete national and sub-national

ranks are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Blackstripe Topminnow

(NatureServe 2008).

Canada and U.S. National Rank (NX) and Provincial/State Rank (SX)

Canada (N2)

Ontario (S2)

United States (N5)

Alabama (S3), Arkansas (S4), Illinois (S5),

Indiana (S4), Iowa (S3), Kansas (S5),

Kentucky (S4S5), Louisiana (S5), Michigan

(S2S3), Mississippi (S5), Missouri (SNR),

Ohio (SNR), Oklahoma (S5), Tennessee

(S5), Texas (S5), Wisconsin (S4)

Canadian Population Size and Status: The Blackstripe Topminnow is ranked as imperilled

(N2) in Canada (NatureServe 2008), and has been listed as Special Concern by the Ontario

Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) (NHIC 2008) and the Committee on the Status of

Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) (COSEWIC 2001). The species is also listed as

Special Concern under the SARA and is included on Schedule 1 of the Act. There are little data

on population size or trends for Blackstripe Topminnow in Canada. Sampling conducted in

September of 2003 in the Lake St. Clair drainage yielded 593 Blackstripe Topminnow from

seven locations: East Otter Creek (83 specimens); East Sydenham River (221); Little Bear

Creek (24); Maxwell Creek (4); North Sydenham River (207); West Otter Creek (33); and,

Whitebread Drain (21) (Mandrak et al. 2006). A comparison of sampling conducted in the

1970s and late 1990s indicates that a comparable number of specimens were captured at most

sites and, although Blackstripe Topminnow were not detected at several sites where they were

previously found, the species was found at several new sites (Mandrak and Holm 2001).

Overall, Blackstripe Topminnow populations in Canada are believed to be stable.

Nationally Significant Populations: The Sydenham River watershed, Little Bear Creek and

Whitebread Drain support the only known populations of Blackstripe Topminnow in Canada and

are, therefore, nationally significant.

1.4

Needs of the Blackstripe Topminnow

1.4.1 Habitat and biological needs

The Blackstripe Topminnow prefers small to large, low-gradient streams, sloughs and pools of

intermittent tributaries, with moderate to high turbidity, and is apparently tolerant of a wide range

in water quality (McAllister 1987, Dextrase et al. 2003). Substrates at capture sites include silt,

sand, clay, rubble and boulder (Becker 1983, Mandrak and Holm 2001), and water clarity

5

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

ranged from 5 – 40 cm (Mandrak and Holm 2001). In Canada, McAllister (1987) found the

species to be particularly abundant in pools of intermittent tributaries of Black Creek, where

aquatic vegetation and riparian areas had not been destroyed by livestock. The species is

highly associated with areas containing abundant riparian and aquatic vegetation that offer a

source of food as well as cover. In Michigan, spawning occurred from May to the third week of

August while in Wisconsin, spawning occurred from June to July (Mandrak and Holm 2001).

Eggs are laid on filamentous algae or other types of aquatic vegetation (Becker 1983). In the

absence of aquatic vegetation, the species will spawn over detritus and leaf litter (Smith 1979).

Blackstripe Topminnow occupy deeper waters during the winter and migrate to shallow water in

late March or early April where they are typically found in the top 2.5 cm of water (Carranza and

Winn 1954).

The diet of the Blackstripe Topminnow includes a large proportion of terrestrial insects but the

species has also been known to consume aquatic insect larvae, molluscs, spiders and

microcrustaceans (Mandrak and Holm 2001). The species also consumes filamentous algae,

which some authors consider to be only incidentally ingested, while other authors consider it to

be an important food item (Mandrak and Holm 2001).

1.4.2 Ecological role

The Blackstripe Topminnow plays an important role in the ecosystem in terms of the exclusivity

with which it feeds on terrestrial insects in the summer (McAllister 1987); aside from the

Redside Dace (Clinostomus elongatus), few other Canadian fish species feed on terrestrial

insects to this extent. The Blackstripe Topminnow may also be an important prey fish where it

is abundant (Dextrase et al. 2003).

1.4.3 Limiting factors

Population sizes of the Blackstripe Topminnow are limited by the amount of riparian vegetation,

aquatic vegetation and riparian terrestrial insect fauna (Dextrase et al. 2003).

6

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

2.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – PUGNOSE MINNOW

2.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC

October 2009

Date of Assessment: May 2000

Common Name (population): Pugnose Minnow

Scientific Name: Opsopoeodus emiliae (Hay, 1881)

COSEWIC Status: Special Concern

Reason for Designation: This species is limited to a small area of southwestern Ontario and is

susceptible to aquatic plant removal and siltation.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated as Special Concern in April 1985. Status re-examined

and confirmed in May 2000. Last assessment based on an update status report.

2.2

Description

The following description has been adapted from Cudmore and Holm (2000). The Pugnose

Minnow (Opsopoeodus emiliae Hay, 1881) (Figure 4) is a small cyprinid with a maximum length

of 64 mm TL. It has a small upturned mouth, a black lateral band extending from the tail to the

snout, and a criss-cross pattern of scaling particularly evident on the upper body. Adult males

have a dusky or black dorsal fin with a white bar in the middle that intensifies during the

spawning season. The Pugnose Minnow usually has nine principal dorsal rays, unlike any other

Canadian minnow. This species has five, ridged pharyngeal teeth in one row on each side.

There may occasionally be a fleshy barbel at the posterior end of one or both sides of the lower

lip. Spawning males develop patches of small tubercles on the snout and chin. The Pugnose

Minnow can be distinguished from similar species such as the Pugnose Shiner (Notropis

anogenus), and other blackline shiners (e.g., Blackchin Shiner [N. heterodon], Blacknose Shiner

[N. heterolepis]), primarily by its nine principal dorsal rays; the Pugnose Shiner and other

blackline shiners have eight. Additionally, the Pugnose Minnow can be differentiated from the

Pugnose Shiner by the dark lateral band that extends onto the nose, but not the chin, as is seen

in the Pugnose Shiner.

Figure 4. Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus emiliae). From Scott and Crossman (1998), with

permission.

7

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

2.3

October 2009

Populations and Distribution

Distribution:

Global Range (Figure 5): The Pugnose Minnow is relatively common and widespread in the

southern United States where it is found from South Carolina and Florida, west to Texas. It is

found in the Mississippi River drainage north to southeastern Wisconsin, and west to

southwestern Ontario. It is less frequently encountered and possibly disappearing from the

more northern areas of its range (Cudmore and Holm 2000).

Figure 5. North American distribution of the Pugnose Minnow

(Cudmore and Holm 2000).

Canadian Range (Figure 6): In Canada, the Pugnose Minnow is known only from a small area

in southwestern Ontario where it was first recorded in 1935 from Mitchell’s Bay in Lake St. Clair.

It has also been collected from several small tributaries of Lake St. Clair since 1980 (Channel

Ecarte, East Otter Creek, Maxwell Creek, Little Bear Creek, McDougall Drain and an un-named

agricultural ditch north of Walpole island), as well as the Detroit River (first recorded in 1940),

western Lake Erie (1994), Sydenham River (1972 – North Sydenham; 1979 – lower East

Sydenham) and Thames River (1968) (Cudmore and Holm 2000, Dextrase et al. 2003, EERT

2008). In 2003, the species was captured for the first time in Whitebread Drain (Lake St. Clair

drainage) (Mandrak et al. 2006). Additionally, a single specimen was purportedly collected from

Long Point Bay in 2003 (EERT 2008), representing the most easterly location for this species;

however, the voucher specimen for this record cannot be located and verification is not currently

possible. In 2007, a single specimen was captured on the south shore of Lake St. Clair by the

8

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

OMNR (G. Yunker, OMNR, pers. comm. 2008), representing a new location for the species in

the lake.

9

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Figure 6. Canadian distribution of the Pugnose Minnow.

10

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Percent of Global Distribution in Canada: Less than 5% of the species’ global range occurs

in Canada.

Population Size and Status:

Global Population Size and Status: There are an estimated 10 000 to more than 1 million

Pugnose Minnow globally (NatureServe 2008) and the species is considered to be globally

secure (G5) (NatureServe 2008). However, it is rare and may be declining in the northern part

of its range (Cudmore and Holm 2000). It is ranked as presumed extirpated (SX) in West

Virginia and critically imperilled (S1) in Michigan and Ohio (NatureServe 2008). Complete

national and sub-national ranks for the species are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Pugnose Minnow (NatureServe

2008).

Canada and U.S. National Rank (NX) and Provincial/State Rank (SX)

Canada (N2)

Ontario (S2)

United States (N5)

Alabama (S5), Arkansas (S3S4), Florida

(SNR), Georgia (S3), Illinois (S2S3),

Indiana (S2), Iowa (S3), Kentucky (S4S5),

Louisiana (S5), Michigan (S1), Minnesota

(S4), Mississippi (S5), Missouri (S4), Ohio

(S1), Oklahoma (S3), Pennsylvania (SNA),

Tennessee (S5), Texas (S4), West Virginia

(SX), Wisconsin (S3)

Canadian Population Size and Status: The Pugnose Minnow is ranked as imperilled (N2) in

Canada (NatureServe 2008), and is listed as Special Concern by the OMNR (NHIC 2008) and

COSEWIC (COSEWIC 2000). It is also listed as Special Concern under the SARA and is on

Schedule 1 of the Act. The number of Pugnose Minnow in Canada is unknown and there are

insufficient data available to determine population trends (Cudmore and Holm 2000). The

species is not common in collections, which suggests that numbers are relatively low; however,

population sizes likely fluctuate from year to year. Recent captures of the Pugnose Minnow at

most sites where it was captured previously, and at new sites, indicate that the species is

maintaining itself in Canada (Cudmore and Holm 2000). Twenty-eight Pugnose Minnow were

captured from six locations throughout the Lake St. Clair drainage in 2003 (Mandrak et al.

2006): East Otter Creek (1 specimen); East Sydenham River (3); Little Bear Creek (3); Maxwell

Creek (2); North Sydenham River (1); and, Whitebread Drain (18). In 2007, one specimen was

caught along the south shore of Lake St. Clair by the OMNR during a seine survey. Overall,

Pugnose Minnow populations in Canada are believed to be stable.

Nationally Significant Populations: None have been identified.

2.4

Needs of the Pugnose Minnow

2.4.1 Habitat and biological needs

It is believed that the Pugnose Minnow prefers clear, slow-moving waters with abundant

vegetation (Scott and Crossman 1998). However, in Canada, this species has been collected

from turbid environments with small amounts of aquatic vegetation. Other physical

characteristics of capture sites included substrates of silt, muck and detritus, and the presence

of other cover such as boulders and woody debris (Cudmore and Holm 2000). Therefore, it

would seem that, in Canada, the species is found in turbid, slow-moving or still waters with or

11

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

without vegetation over clay, silt or sand substrates (Cudmore and Holm 2000). The spawning

season for the Pugnose Minnow occurs in late May to mid-June (Cudmore and Holm 2000).

Spawning is believed to take place at depths of 0 – 2 m in areas with submergent and emergent

aquatic vegetation over substrates of silt, clay or sand (Lane et al. 1996c). However, Cudmore

and Holm (2000) stated that males select and defend a flat surface, such as the underside of a

rock, as a spawning site. Eggs are laid in clusters on the underside of the flat surface over a

period of 6 – 7 days and are defended by the male (Cudmore and Holm 2000). Nursery habitat

for the Pugnose Minnow is thought to occur in areas containing abundant aquatic vegetation

and substrates of silt and sand, at depths of 0 – 2 m (Lane et al. 1996b).

The Pugnose Minnow feeds on a variety of small insects (e.g., Diptera and larval Trichoptera),

crustaceans, filamentous algae, and occasionally on larval fishes and fish eggs (Parker et al.

1987).

2.4.2 Ecological role

The species’ upturned mouth may be an adaptation to mid-water or surface feeding habits

(Scott and Crossman 1998). Apparent low population levels likely reduce its value as a forage

species (Cudmore and Holm 2000). The egg clustering and parental care behaviour of the

Pugnose Minnow is a complex breeding strategy and, along with that of species in the

Pimephales and Cyprinella genera, is unique to North American cyprinids (Cudmore and Holm

2000).

2.4.3 Limiting factors

Factors that limit the survival and health of the Pugnose Minnow in Canada are unknown

(Cudmore and Holm 2000). During the spawning season, the male Pugnose Minnow has an

elaborate courtship display, which may require clear water to be effective (Cudmore and Holm

2000).

12

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

3.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – SPOTTED SUCKER

3.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC

October 2009

Date of Assessment: May 2005

Common Name (population): Spotted Sucker

Scientific Name: Minytrema melanops (Rafinesque, 1820)

COSEWIC Status: Special Concern

Reason for Designation: This species is restricted to southwestern Ontario. The greatest

threat to it is habitat degradation through increased erosion and turbidity. The Spotted Sucker

is also at risk in Pennsylvania but not at risk in Michigan (where it is S3-vulnerable), making

rescue effect moderate at best.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Special Concern in April 1983. Status re-examined and

confirmed in April 1994, November 2001 and May 2005. Last assessment based on an update

status report.

3.2

Description

The following description was adapted from COSEWIC (2005a). The Spotted Sucker

(Minytrema melanops Rafinesque, 1820) (Figure 7) is a medium-sized sucker that ranges

between 230 and 380 mm TL as adults. Specimens as large as 500 mm TL have been

captured in the Canadian waters of the Detroit River (S. Staton, DFO, pers. obs.). Most

individuals weigh less than 1000 g, although specimens over 1300 g have been reported. This

species is distinguished from other catostomid species by the presence of 8-12 parallel rows of

dark spots on the base of the scales. Juvenile Spotted Sucker are torpedo-shaped and

resemble the White Sucker (Catostomus commersonii). Adult Spotted Sucker resemble

redhorse suckers (Moxostoma spp.). The dorsal surface is brown to dark green, the sides silver

to bronze and the ventral surface is white and silvery. Breeding males have two dark lateral

bands separated by a pinkish band along the midside. Tubercles are present on the snout, anal

fin and both lobes of the caudal fin of males. Fewer tubercles are present around the lower

cheek and eye, and on the underside of the head.

Figure 7. Spotted Sucker (Minytrema melanops; male). © Joseph R. Tomelleri.

13

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

3.3

October 2009

Populations and Distribution

Distribution:

Global Range (Figure 8): The Spotted Sucker is widely distributed in central and eastern North

America (COSEWIC 2005a). It occurs in the drainages of lakes Huron, Michigan, Erie and St.

Clair, as well as throughout much of the Mississippi River basin and along the coastal plain from

Texas to North Carolina. It is known from 23 states and the province of Ontario (COSEWIC

2005a).

Figure 8. Global range of the Spotted Sucker (COSEWIC 2005a).

Canadian Range (Figure 9): In Canada, the Spotted Sucker is rare and found only in the

extreme southwestern region of Ontario. Its first recorded capture was from Lake St. Clair in

1962 (Campbell 1994; cited in COSEWIC 2005a). Since then, the species has been recorded

from Lake Erie, the Detroit River, the St. Clair River, the Sydenham River watershed and

several associated tributaries, and the lower Thames River (COSEWIC 2005a). In 1996, a

single specimen was caught in Maxwell Creek (Lake St. Clair drainage), which represented a

new occurrence for the Spotted Sucker. Similarly, a new record for the species occurred when

a single juvenile was captured from Bear Creek (North Sydenham River drainage) in 1997

(COSEWIC 2005a). In 2003, the species was caught for the first time in Whitebread Drain, a

tributary of the St. Clair River (Mandrak et al. 2006). Collections in Lake Erie are restricted to

the western basin, from the mouth of the Detroit River to Rondeau Bay (EERT 2008)

.

14

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Figure 9. Canadian range of the Spotted Sucker.

15

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Percent of Global Distribution in Canada: Less than 5% of the species’ global distribution is

currently found in Canada (Dextrase et al. 2003).

Population Size and Status:

Global Population Size and Status: The Spotted Sucker is globally Secure (G5) (NatureServe

2008) but declines have been reported in the northern part of its range (Becker 1983). It is

ranked as critically imperilled (S1) in Pennsylvania and vulnerable (S3) in Illinois, Iowa, Kansas,

Michigan and Texas (NatureServe 2008). Complete national and sub-national ranks for the

Spotted Sucker are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Spotted Sucker (NatureServe

2008).

Canada and U.S. National Rank (NX) and Provincial/State Rank (SX)

Canada (N2)

Ontario (S2)

United States (N5)

Alabama (S5), Arkansas (S4), Florida

(SNR), Georgia (S5), Illinois (S3), Indiana

(S4), Iowa (S3), Kansas (S3), Kentucky

(S4S5), Louisiana (S5), Michigan (S3),

Minnesota (SNR), Mississippi (S5),

Missouri (SNR), North Carolina (S4), Ohio

(SNR), Oklahoma (S4), Pennsylvania (S1),

South Carolina (SNR), Tennessee (S5),

Texas (S3), West Virginia (S4), Wisconsin

(S5)

Canadian Population Size and Status: The Spotted Sucker is ranked as imperilled (N2) in

Canada (NatureServe 2008) and listed as Special Concern by the OMNR (NHIC 2008) and

COSEWIC (COSEWIC 2005a). The species is also listed on Schedule 1 of the SARA as a

species of Special Concern. Available information regarding population size or trends for the

Spotted Sucker in Canada is limited. In 2002 and 2003, 27 Spotted Sucker were captured from

14 sites throughout the Sydenham River and nine were captured from six sites along the Detroit

River (COSEWIC 2005a, Mandrak et al. 2006, Edwards et al. in press). One specimen was

caught in Turkey Creek (tributary of the Detroit River) in 2003, and three specimens were

caught in the Detroit River in 2004 (Edwards et al. in press). Seventeen Spotted Sucker were

captured from five sites on the St. Clair River in 2004 (Edwards et al. 2006a). In 2002, nine

specimens were collected from two locations along the Canard River (COSEWIC 2005a). A

total of 51 Spotted Sucker have been caught in Lake St. Clair during annual OMNR trap-net

surveys (surveys began in 1974), with the most recent records occurring in 2007 (three

specimens caught) (M. Belore, OMNR, pers. comm. 2008). In the Thames River, Spotted

Sucker was caught in 2003 at three sites located approximately 75 km upstream of historical

records (COSEWIC 2005a). A single individual was caught in 2000 from western Lake Erie; it

was the only record from over 187 000 fish sampled during an 11-year sampling period

(COSEWIC 2005a). Between 1962 and 1992, approximately 24 Spotted Sucker were captured

from Canadian waters. Since 1992, approximately 67 individuals have been caught. Fifty-four

of the 67 Spotted Sucker collected since 1992 were collected in 2002 and 2003. Almost all

individuals collected have been adults (COSEWIC 2005a). Although Spotted Sucker captures

have increased in recent years, this is believed to be a result of increased sampling effort using

more efficient methods as well as improved species identification, rather than an actual increase

16

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

in species abundance. Overall, Spotted Sucker populations are believed to be stable in

Canada.

Nationally Significant Populations: None have been identified.

3.4

Needs of the Spotted Sucker

3.4.1 Habitat and biological needs

The Spotted Sucker typically inhabits long, deep pools of small- to medium-sized rivers over

substrates of clay, gravel or sand. They have also been collected from a variety of other

habitats including large rivers, oxbows and backwater areas, impoundments and small turbid

creeks (COSEWIC 2005a). In Canada, Spotted Sucker has been collected from small- to

medium-sized rivers such as the Thames and Sydenham rivers, large riverine habitats in the St.

Clair and Detroit rivers, and along the shores of lakes Erie and St. Clair (COSEWIC 2005a).

Substrates at capture sites in Ontario range from hard clays to sand, gravel and rubble (Parker

and McKee 1984). Specimens have also been reported from areas with abundant aquatic

macrophytes (COSEWIC 2005a) and almost all Spotted Sucker capture locations in the Detroit

and St. Clair rivers in 2003 and 2004 had abundant macrophytes (Edwards et al. 2006a,

Edwards et al. in press). It is believed that the species prefers clear, warm waters with low

turbidity levels (Trautman 1981); however, in Canada, Spotted Sucker has been collected from

rivers with moderate to high turbidity (COSEWIC 2005a). It is considered to be more tolerant of

siltation than other sucker species, especially if the siltation is only intermittently heavy (Parker

and McKee 1984). Spawning occurs in spring to early summer when water temperatures are

between 12 and 19°C (McSwain and Gennings 1972). Spawning habitat of the Spotted Sucker

is typically located in clean riffle areas (McSwain and Gennings 1972) at depths of 0 – 1 m over

hard substrates such as rubble, gravel, sand and hard pan clay (Lane et al. 1996c). Nursery

habitat is believed to be depths of 0 – 2 m in areas containing aquatic vegetation (Lane et al.

1996b).

Juvenile and adult Spotted Sucker feed on a variety of benthic organisms such as molluscs,

chironomids and small crustaceans (White and Haag 1977, COSEWIC 2005a). Larval Spotted

Sucker (12 – 15 mm TL) feed at the surface and at mid-water on zooplankton and diatoms, and

at 25 – 30 mm TL, individuals feed over patches of sand and in the shallow backwater of creeks

(White and Haag 1977).

3.4.2 Ecological role

The Spotted Sucker plays an important role in nutrient cycling – it transfers energy from the

benthic food web, where it feeds, to the pelagic food web, where it is preyed upon (COSEWIC

2005a). Juvenile Spotted Sucker are probably preyed upon by piscivorous birds and fishes

(Parker and McKee 1984).

3.4.3 Limiting factors

As most of the range of the species is located in the United States, water temperature may be

limiting its northern extent of distribution (COSEWIC 2005a). Dissolved oxygen and water

temperatures may act as limiting factors to the Spotted Sucker but this has not been verified.

17

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

4.0

SPECIES INFORMATION – WARMOUTH

4.1

Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC

October 2009

Date of Assessment: May 2005

Common Name (population): Warmouth

Scientific Name: Lepomis gulosus (Cuvier, 1829)

COSEWIC Status: Special Concern

Reason for Designation: This species has a very restricted Canadian distribution, existing at

only 4 locations along the Lake Erie shore between Point Pelee and Long Point. It is sensitive

to habitat change which results in loss of aquatic vegetation.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Special Concern in April 1994. Status re-examined and

confirmed in November 2001 and in May 2005. Last assessment based on an update status

report.

4.2

Description

The following description has been adapted from Trautman (1981) unless otherwise noted. The

Warmouth (Lepomis gulosus Cuvier, 1829) (Figure 10) is a small to medium- sized fish that

ranges from 100 to 240 mm TL (Eakins 2007). It is characterized by having a large mouth, with

the posterior end of the upper jaw extending well beyond the anterior margin of the eye, usually

to the centre, or beyond, in adults. Three to five dark grey or lavender bands radiate back from

the snout and eye, the opercle flap is black with a red spot (adults only) on a yellow edge (Page

and Burr 1991) and the pectoral fin is short, with a rounded tip. Tiny teeth are present on the

tongue. Colouration is light yellow-olive to dark olive-green, with lighter vermiculations and dull

bluish, purplish and golden reflections. Six to 11 chain-like, double bands of dark olive are

present on the back and sides. The anal, caudal and dorsal fins are boldly vermiculated and the

paired fins are unspotted and transparent or olive. A brilliant orange spot is present at the base

of the posterior three dorsal rays in breeding males.

The Warmouth can be distinguished from other sunfish species (Lepomis spp.) found in the

Great Lakes basin by its large mouth and dark bands radiating backward from the eye. It is the

only species in the genus Lepomis that has teeth on its tongue (Page and Burr 1991). The

Warmouth has fewer anal fin spines (3) than crappies (Pomoxis spp., 5-7) and Rock Bass

(Ambloplites rupestris, 5-7) (Trautman 1981).

Figure 10. Warmouth (Lepomis gulosus). © Joseph R. Tomelleri.

18

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

4.3

October 2009

Populations and Distribution

Distribution:

Global Range (Figure 11): The Warmouth is widely distributed in the Mississippi, Atlantic and

Great Lakes drainages of eastern North America. In the Mississippi drainage, it is found from

the Gulf of Mexico north to Wisconsin, and from western New York in the east to New Mexico in

the southwest. In the Atlantic drainage, it is found from Alabama and Florida north to North

Carolina. Within the Great Lakes basin, disjunct populations are found in Illinois, Indiana,

Michigan, New York, Ohio, Ontario and Wisconsin (COSEWIC 2005b).

Figure 11. Global distribution of Warmouth (COSEWIC 2005b).

Canadian Range (Figure 12): In Canada, Warmouth has been captured at only four main

localities, all within the Lake Erie drainage. The species was first recorded in Canada in 1966

from Rondeau Provincial Park. It has subsequently been captured from Point Pelee National

Park (first recorded in 1983), Long Point Bay (2004) and Big Creek National Wildlife Area

(NWA; Long Point region) (2004) (Crossman and Simpson 1984, COSEWIC 2005b). In 2007,

Warmouth was also detected for the first time at Turkey Point (Long Point region) (S. Staton,

pers. obs.). Warmouth was also reported from Duck Creek (tributary of Lake St. Clair) (Leslie

and Timmins 1998); however, the voucher specimen for this record has been lost and cannot be

verified (COSEWIC 2005b).

19

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Figure 12. Canadian distribution of Warmouth.

20

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Percent of Global Distribution in Canada: Less than 5% of the species’ global distribution is

currently found in Canada.

Population Size and Status:

Global Population Size and Status: Population estimates for Warmouth in the United States

are unavailable but the species is considered globally secure (G5) (NatureServe 2008). It is

ranked as imperilled (S2) in Pennsylvania and West Virginia and as vulnerable (S3) in Illinois

(NatureServe 2008). Complete national and sub-national ranks for Warmouth are listed in

Table 4.

Table 4. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national ranks for Warmouth (NatureServe 2008).

Canada and U.S. National Rank (NX) and Provincial/State Rank (SX)

Canada (N1)

Ontario (S1)

United States (N5)

Alabama (S5), Arizona (SNA), Arkansas

(S4), Delaware (SNA), District of Columbia

(SNA), Florida (SNR), Georgia (S4S5),

Idaho (SNA), Illinois (S3S4), Indiana (S4),

Iowa (SNR), Kansas (S4S5), Kentucky

(S4S5), Louisiana (S5), Maryland (S3?),

Michigan (S5), Mississippi (S5), Missouri

(SNR), Nevada (SNA), New Jersey (SNA),

New Mexico (SNA), New York (SNA),

North Carolina (S5), Ohio (SNR),

Oklahoma (S5), Oregon (SNA),

Pennsylvania (S2), South Carolina (SNR),

Tennessee (S5), Texas (S5), Virginia (S5),

Washington (SNA), West Virginia (S2),

Wisconsin (S4)

Canadian Population Size and Status: Warmouth is ranked as critically imperilled in Canada

(N1) and Ontario (S1) (NatureServe 2008) and is listed as Special Concern by the OMNR

(NHIC 2008) and COSEWIC (COSEWIC 2005b). It is also on Schedule 1 and listed as a

species of Special Concern under the SARA. There are few data available regarding the size of

Warmouth populations in Canada. A fish community survey of Point Pelee National Park in

2002 and 2003 captured 657 Warmouth from 87 of 117 sites (Surette 2006). Most of the

specimens were juveniles and many were likely recaptures. Larger individuals were PIT-tagged

(93 specimens); however, too few fish were recaptured (three specimens) to estimate the

population size (Surette 2006). Since it was first captured from Rondeau Bay in 1966, only 15

specimens have been caught, eight of them in the late 1960s, two in 1999, two in 2005 and

three in 2007 (COSEWIC 2005b, Edwards et al. 2006b, A. Dextrase, unpubl. data). Until 2005,

only four specimens had been caught from Long Point Bay (one juvenile in 2003, and three

adults at the mouth of Big Creek NWA in 2004), making it difficult to determine if an established

population exists (COSEWIC 2005b). However, in 2005, 11 specimens were caught within Big

Creek NWA (Marson et al. in press), providing further support for the presence of an established

population. A single specimen was also caught by the OMNR in 2007 (M. Belore, pers. comm.

2008); however, a voucher specimen is not available and the record cannot be verified. In

2007, a new Warmouth record was collected at Turkey Point (Long Point region). It is possible

21

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

that this record represents a stray from Long Point Bay, as only one specimen was captured,

despite intensive sampling effort.

Nationally Significant Populations: Long Point Bay, Big Creek NWA, Point Pelee National

Park and Rondeau Bay support the only known populations of Warmouth in Canada and should

therefore be considered nationally significant.

4.4

Needs of the Warmouth

4.4.1 Habitat and biological needs

The habitat requirements of the Warmouth appear to be similar to other members of the sunfish

family. It is a warmwater species that prefers vegetated habitats in lakes, streams and wetlands

(Crossman et al. 1996, Scott and Crossman 1998, Coker et al. 2001, COSEWIC 2005b). In

Ontario, it is found only in three coastal wetlands of Lake Erie. Adults are found in areas having

depths of 0.1 – 5 m, with submergent and emergent vegetation over sand or silt substrates

(Page and Burr 1991, Lane et al. 1996a), which was characteristic of Canadian Warmouth

capture sites (e.g., Edwards et al. 2006b). Spawning occurs in the spring or summer, when

water temperatures range between 18 - 32°C, at depths of 0 – 2 m (Lane et al. 1996c,

NatureServe 2008). Spawning habitat is characterized as having both submergent and

emergent vegetation, along with stumps, rocks or clumps of vegetation. Nests are constructed

on a soft, muddy bottom, often among algae or exposed roots of vascular plants. Eggs are

guarded and fanned by the male (Lane et al. 1996c, Coker et al. 2001). Nursery habitat is

typically found at depths of 0 – 2 m and is characterized by submergent vegetation over

substrates of sand, silt or gravel (Lane et al. 1996b).

The Warmouth feeds in both the pelagic and benthic zones, on crustaceans and aquatic insect

larvae when small, and on fishes, crayfishes and molluscs when larger (COSEWIC 2005b).

4.4.2 Ecological role

Unlike most sunfish species, Warmouth exhibits a high degree of piscivory as adults (Coker et

al. 2001) and may be an important mid-level predator as an adult.

Warmouth is a naturalized Canadian species, having naturally colonized Canadian waters

relatively recently (Crossman et al. 1996), and its presence here may be indicative of the effects

of global warming and/or a continuing range expansion following the last period of glaciation

(COSEWIC 2005b).

4.4.3 Limiting factors

The current distribution of Warmouth in Canada is limited by temperature (Crossman et al.

1996). Projected future climate warming scenarios may lead to an expansion in range

(Mandrak 1989).

5.0

THREATS

Blackstripe Topminnow – The Blackstripe Topminnow is threatened by habitat destruction,

including the damage or removal of riparian vegetation (e.g., damage to the riparian vegetation

by livestock access has been noted in the Sydenham watershed) and the loss or disturbance of

emergent and floating aquatic macrophytes (Dextrase et al. 2003). Channelization and wetland

drainage will likely have a negative impact on the Blackstripe Topminnow, and seepage from oil

wells in Black Creek has also been identified as a threat to this surface-feeding species

(Mandrak and Holm 2001, Dextrase et al. 2003). Although the species can be caught at the

22

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

surface using dip nets and makes a hardy aquarium fish (Mandrak and Holm 2001), there is no

evidence that the pet trade in Canada is a threat to the Blackstripe Topminnow.

Pugnose Minnow – Erosion and associated turbidity negatively affect the densely vegetated

habitats that the Pugnose Minnow prefers, and filling or drainage of riparian wetland habitats

would further limit the species. Cudmore and Holm (2000) suggest that turbid water would likely

reduce the effectiveness of the male’s courtship display. Other potential threats have been

identified by the Essex-Erie recovery team and include nutrient loading, exotic species, climate

change, altered coastal processes, harvesting pressure (incidental harvest by baitfishers) and

barriers to movement (EERT 2008).

Spotted Sucker – Habitat degradation, pollution, siltation and dams are identified as the main

threats to the Spotted Sucker (COSEWIC 2005a). The degree to which turbidity limits its

distribution is uncertain as well – the Spotted Sucker has been collected in Canada from waters

with moderate to high turbidity, but the species is generally believed to prefer clear, warm

waters with low turbidity (COSEWIC 2005a). Additional potential threats to the species have

been identified in the Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy and include nutrient loading, exotic species,

climate change, altered coastal process and harvesting pressure (incidental harvest in the

commercial fishing industry) (EERT 2008).

Warmouth – The Warmouth is likely threatened by the loss of its preferred habitat – calm,

vegetated, shallow waters (COSEWIC 2005b). Any declines in water quality, due to siltation,

turbidity and other factors, would likely have a negative effect on the species. Trautman (1981)

indicated that the Warmouth appears to be less tolerant than the Green Sunfish (Lepomis

cyanellus) to siltation and turbidity where their ranges overlap. The Warmouth is abundant at

Point Pelee National Park but is absent from Hillman Marsh (adjacent to Point Pelee National

Park), while the Green Sunfish is present at Hillman Marsh and absent from Point Pelee

National Park. It is not clear if this is a result of interspecific competition (both species exhibit a

high degree of piscivory as adults, unlike other species in the genus Lepomis), abiotic factors

(e.g., turbidity levels) or different colonization histories (COSEWIC 2005b). Additional potential

threats to the species have been identified in the Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy and include

nutrient loading, toxic compounds, exotic species, climate change, altered coastal processes

and barriers to movement (EERT 2008).

As the Warmouth is found only in wetland habitats in Ontario, this has implications for the

management of the nearshore areas of Lake Erie. Any management activities that result in the

degradation of wetland habitats may have a negative impact on the Warmouth.

5.1

Threat classification

Table 5 summarizes all known and suspected threats to the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose

Minnow, Spotted Sucker and Warmouth in Canada. The threat classification parameters are

defined as follows:

Extent – spatial extent of the threat in the waterbody (widespread/localized)

Frequency – the frequency with which the threat occurs in the waterbody

(seasonal/continuous)

Causal Certainty – the level of certainty that it is a threat to the species (High – H, Medium –

M, Low - L)

Severity – the severity of the threat in the waterbody (H/M/L)

23

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

October 2009

Overall Level of Concern – composite level of concern regarding the threat to the species

(H/M/L)

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Sediment Loadings

Nutrient Loadings

Exotic Species

Altered Coastal Processes

Climate Change

Toxic Compounds

Barriers to Movement

Changes to Trophic Dynamics

24

Overall Level of

Concern

(high, medium, low)

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Sediment Loadings

Nutrient Loadings

Exotic Species

Barriers to Movement

Altered Coastal Processes

Toxic Compounds

Climate Change

Incidental Harvest

Severity

(high, medium, low)

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Sediment Loadings

Nutrient Loadings

Exotic Species

Altered Coastal Processes

Climate Change

Incidental Harvest

Barriers to Movement

Blackstripe Topminnow

Widespread

Continuous

Localized

Seasonal

Unknown

Unknown

Pugnose Minnow

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Seasonal

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Spotted Sucker

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Localized

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Localized

Seasonal

Warmouth

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Widespread

Continuous

Unknown

Seasonal

Localized

Continuous

Localized

Unknown

Causal Certainty

(high, medium, low)

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Oil seepage

Channelization

Frequency

(seasonal/continuous)

Specific Threat

Extent

(widespread/localized)

Table 5. Threat classification table (threat information comes from species-specific COSEWIC

reports; additional information adapted from Dextrase et al. [2003] for the Blackstripe

Topminnow, and the Essex-Erie Recovery Team [2008] for the remaining species).

High

Low

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Medium

Low

Unknown

High

High

High

Low

Unknown

Low

Unknown

Unknown

High

High

High

High

Unknown

Medium

Unknown

Unknown

High

High

High

Medium

Unknown

Medium

Unknown

Unknown

High

Medium

High

Low

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Low

Low

High

High

High

High

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Medium

Low

Medium

Medium

Medium

Medium

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Low

Low

High

High

High

Low

Unknown

Low

Low

Low

Low

Medium

Medium

Medium

High

Unknown

Medium

Unknown

Unknown

Unknown

Medium

Medium

Medium

Medium

Unknown

Medium

Low

Low

Low

Management Plan for the Blackstripe Topminnow, Pugnose Minnow,

Spotted Sucker and Warmouth

5.2

October 2009

Description of threats

The following descriptions have been adapted primarily from the Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy

(EERT 2008).

5.2.1 Habitat Loss and Degradation

The loss of wetland and riparian forest habitats across southern Ontario has been dramatic

since the late 1800s. Continued development of wetlands is a concern, primarily for those

wetlands without protection from development pressures. Habitat loss in the form of lake and

river shoreline modifications (e.g., shoreline stabilization projects, docks, marinas) along Lake

St. Clair, the Detroit River and Lake Erie are also a significant and ongoing concern.

Modification of inland watercourses through subsurface and surface drainage activities has also

negatively affected hydrological networks, and reduced the extent and quality of aquatic habitat.

Livestock access to watercourses in both the Sydenham and Thames watersheds has resulted

in the destruction of important riparian habitats that provide cover and a source of food for many

fish species, in particular the Blackstripe Topminnow (in the Sydenham River). Riparian strips

have also been destroyed in recreational or urban areas, more so in the Thames River

watershed, where the grass is often mowed to the edge of the waterway (TRRT 2005).

5.2.2 Sediment Loading

Sediment loading affects aquatic habitats through decreasing water clarity, increasing siltation

of substrates, and may have a role in the selective transport of pollutants, including phosphorus.

Increasing turbidity, as a result of sediment loading, can reduce the amount of aquatic

vegetation present, as sunlight cannot penetrate far into the water. This can have detrimental

impacts on species that rely on dense growths of submerged macrophytes, such as the

Pugnose Minnow and the Warmouth. Sediment loading, and resulting turbidity and siltation,

can impact species by affecting their respiration, vision and prey abundance, and smothering

eggs deposited on the substrate.

5.2.3 Nutrient Loading

Nutrients (nitrates and phosphates) enter waterbodies through a variety of pathways, including

manure and fertilizer applications to farmland; manure spills; sewage treatment plants; and,