The Superior Vena Cava: Conventional Projections

advertisement

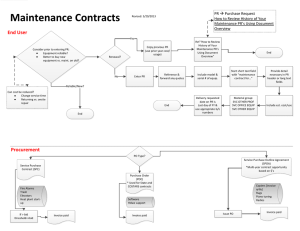

The Superior Vena Cava: Conventional By Benjamin S ALREADY noted, anomalies of the SVC are fairly common and are nicely demonstrated on CT. I have illustrated them here in conventional frontal projection so that you can suspect or recognize them from the plain films. Figure 1 illustrates double SVC and Fig 2 shows a left SVC entering the left coronary sinus. A left SVC can be recognized on the plain PA teleroentgenogram as a subtle vertical interface extending caudally from the left clavicle to the heart overlapping or lying just lateral to the aortic knob. This interface vanishes as it approaches the clavicle because of its location in the anterior mediastinum (the cervicothoracic sign’). Another variant of the SVC is idiopathic dilatation (Fig 3).2 The enlarged vessel may mimic a A (Ai Subtraction Figl. Two cases of double SVC. patient. Venous catheterization of heart via the right and passes retrograde into the left SVC. W Same catheter fills the left SVC and coronary sinus. Seminars in Roentgenology, Vol XXIV, No 2 (April), 1989: Projections Felsont mediastinal mass and lead to additional studies and even unnecessary surgery. In my own experi- From the Department of Radiology, University Hospital, Cincinnati. fDr Felson died Ott 22, 1988. Address reprint requests to Benjamin F&on, MD, Department of Radiology, #742, University Hospital, Cincinnati, OH 45247. 0 I989 by W.B. Saunders Company. 0037-I 98x/89/2402-0005$5.00/0 bilateral various angiogram. Note the interconnecting v&n. arm. The catheter her entered the coronary sinus from the patient as (B). Contrast injection into the left innominate pp 9 1-95 (6) Another right atrium vein via the 91 BENJAMIN Fig 1. Fig 2. Left SVC en route to the coronary sinus. Lateral to the aortic knob (black arrow). The shadow Venous phase of an angiocardiogram shows contrast sinus and right atrium. FELSON (Cont’d). (Al PA telaroentgenogram. disappears as it approachas filling of the anomalous left Noto the vartkal intarfaca the davii IcMvicathwacic cava and its entry into the (white arrow) sign’). (81 dilated coronary SUPERIOR VENA CAVA: CONVENTIONAL PROJECTIONS Fig 3. Idiopathic difatation of the SVC simulated. The shadow, which disappears injection shows the dilated right SVC. Fig 4. Jugular lymph sac. This rare anomalous vessel lies at the junction of the thoracic duct and left internal jugular vein. (A) Plain film. A soft tissue mass (arrow) bulges from the left supraclavioular region. It was easily compressible. (B) Brachial venogrsm. Retrograde filling of the sac is shown (arrow). in a young woman. (A) Teleroantgenogram. st the clavicle, decreased with the 93 Valsalva A right superior msneuver. mediaatfnal (B) Contrast mass is medium BENJAMIN Fig 4. ence it is encountered most often in teenage girls. The bulging shadow clearly diminishes on the Valsalva maneuver, but remember that a bona fide mediastinal mass may occasionally shift medially with this procedure. It is sometimes necessary to perform CT with contrast enhancement to make the diagnosis. The prominent SVC need not be dilated, but merely positioned more to the right than normal.’ Table 1. Superior Common 1. Aneurysm 2. Vena of aorta latrogenic uloatrial Caval or great fag, pacemaker, shunt) 3. Lymphadenopathy Obstruction* artery; AV fistula central line catheter, ventric- fesp lymphoma) 4. Mediastinal tuberculosis, fibrosis or granuloma ergotrates, irradiation, 5. Neoplasm of lung, (eg, goiter, superior (eg, histoplasmosis, idiopathic) esophagus, thyroid, sulcus carcinoma, or mediastinum cystic hygroma, thymoma) Uncommon 1. Axillary 2. Behcet vein S 3. Congestive 4. Idiopathic 5. Mediastinal 6. Mediastinitis, thrombosis heart with failure emphysema, 11. 12. 13. 14. severe: tension pneumothorax acute 7. Myxoma of right atrium 8. Osteomyelitis of clavicle 9. Pericarditis. constrictive 10. Pneumoconiosis (coalworkers, erate mass Postoperative Sarcoidosis extension (eg, cogenital silicosis) heart with conglom- disease) Thrombosis (eg, polycythemia Vera) Trauma (eg, laceration, transection, mediastinal tome) hema- FELSON (Cont’d). Another congenital aberration you should be aware of, not of the SVC but rather of the innominate venous system, is the jugular lymph sac. This rare anomaly occurs at the junction of the internal jugular vein and subclavian vein, at the site of entry of the thoracic duct. Its derivation is interesting. The lymphatic vessels embryologically stem from the venous system. Well-formed lymphatic valves prevent reflux of blood into the lymphatics. The only major connection between the two systems retained at birth is the site of entry of the thoracic duct adjacent to the origin of the innominate vein. With incompetence or absence of valves at this site, the connection may be wideopen and dilated. This is called the jugular lymph sac and may be apparent clinically. It is usually found in the left supraclavicular fossa but may be present on the right side instead. It enlarges on Valsalva maneuver. The diagnosis is readily confirmed by either angiography or lymphography (Fig 4).4*5 Jugular lymph sac is usually mistaken for a venous aneurysm and surgically removed, an unnecessary intrusion.6’7 As stated elsewhere in this Seminar, SVC obstruction has many causes. Table 1 is a Gamut listing them.8 I have been surprised at how often patients with complete SVC obstruction show no clinical evidence of the condition. Even with head lowered, the dilated veins and other signs of superior caval obstruction may be lacking. The reason I can make this statement so emphatically is that for many years whenever I have noted a SUPERIOR VENA CAVA: Fig 6. WC obstruction the accessory hemiazygos brad&l venogrem shows is notching the right fdth CONVENTIONAL PROJECTIONS with rib notching. (A) The left eighth rib is ckarty notched (verticalarrow). v&n (the superior intercostal vein) juts out from the aodc knob Omrii obstruction of the SVC (arrow) with extensive collaterals. including a tortuous rib. Autopsy showed fibrocalcific medisstinitis obstructing the superior cava. right superior mediastinal or RUL mass I begin my study with a barium swallow, seeking evidence of downhill varices. I have demonstrated them in about half the cases of SVC obstruction. If the varices involve the upper esophagus, I An enlarge4 arrow). intercostal brench of ISI Right vein that insist on venous angiography, which to date has never failed to demonstrate the SVC obstruction.’ Rib notching from intercostal venous collaterals, though rare, is also an indication of SVC obstruction (Fig 5).’ REFERENCES 1. Felson B: Chest roentgenology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1973 2. Bell MJ, Gutierrez JR, Dubois JJ: Aneurysm of the superior vena cava. Radiology 1970;95:3 17-8 3. Drasin E, Sayre RW, Castellino RA: Non-dilated superior vena cava presenting as a superior mediastinal mass. J Can Assoc Radio1 1972;23:273-4 4. Steinberg I, Watson RC: Lymphangiographic and angiographic diagnosis of persistent jugular lymph sac. New Engl JMed 1966;275:1471-4 5. Gordon DH, Rose JS, Kottmeier P, et al: Jugular venous ectasia in children. Rudiotogy 1976;118: 147-9 6. Koh SJ, Brown RE, Hollabaugh RS: Venous aneurysm. South Med J 1984;77:1327-8 7. Tatezawa T, Shiozawa Z, Akisada M, et al: Venous angioma of the neck in a child. Pediotr Rndiol 1979;8:122-3 8. Felson B, Reeder MM: Gamuts in radiology (ed 2). Cincinnati: Audiovisual Radiology of Cincinnati, 1987