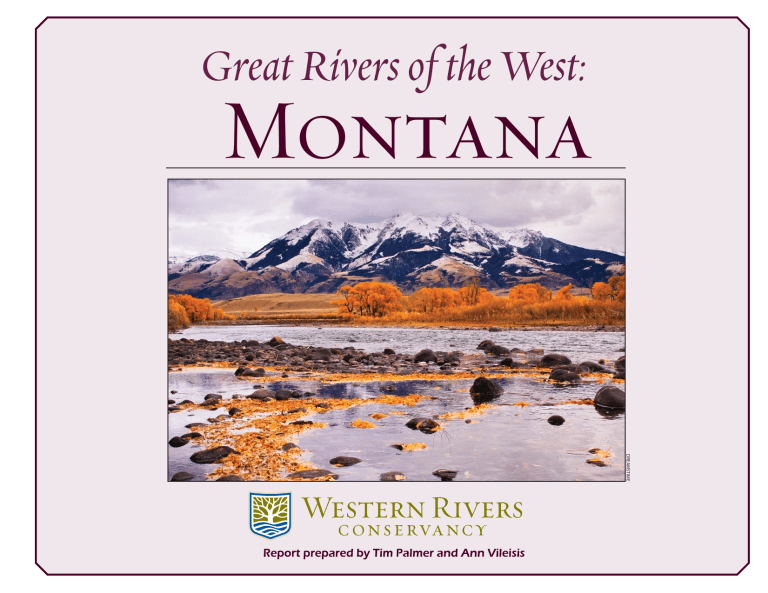

Montana - Western Rivers Conservancy

advertisement