A Taste for Consistency and Survey Response Behavior

advertisement

A Taste for Consistency and Survey Response

Behavior∗

Armin Falk† and Florian Zimmermann‡

October 2012

Abstract

This paper studies how a taste for consistency affects decision making. Our

application is response behavior in surveys. In particular, we show that the inclusion

of questions can affect answers to subsequent related questions. The reason is that

participants want to respond in a consistent way. Studying three different surveys,

we find a systematic effect of the inclusion of additional questions. The effects are

large and reveal how easy survey responses can be manipulated. For example, we

find that a subtle manipulation reduced the number of people who agreed that a

murderer should be imprisoned for the rest of his life by more than 20 percentage

points.

JEL classifications: C83, C91, D03

Keywords: Consistency, Experiments, Survey Design, Social Influence

∗

We thank Jürgen Schupp and participants of the 2011 CESifo Area Conference on Applied Microeconomics for helpful comments and discussions.

†

University of Bonn, CEPR, IZA, CESifo, DIW, MPI - Address: University of Bonn, Adenauerallee

24, 53113 Bonn, Germany; (e-mail: armin.falk@uni-bonn.de)

‡

University of Bonn, IZA - Address: University of Bonn, Adenauerallee 24, 53113 Bonn, Germany;

(e-mail: florian.zimmermann@uni-bonn.de)

1

1

Introduction

In this paper, we examine how a desire for consistency can affect decision making. We

demonstrate the importance of this behavioral pattern in the context of survey responses.

People often experience pressure to live up to prior actions, statements or commitments.

In social psychology this pressure is referred to as a desire or preference for consistency

(see Cialdini (1984)). This desire to behave and appear consistent can be a powerful

determinant of behavior. Given a certain choice history, we strive to be consistent with

that history, even if doing so entails costs. We also want people in our environment to

behave consistently. We first present a simple reduced-form model that helps to conceptualize a desire for consistency and allows predictions for how a taste for consistency can

influence response behavior in a survey. We then provide evidence from three surveys we

conducted that underscore how a desire for consistency can change survey answers.1

The way a taste for consistency can affect answers to survey questions is simple.

The basic idea is to “tempt” a person to make a biased statement in a first question.

In a second step, she faces a question related to that statement and the pressure to

respond consistently. Thereby, the simple addition of one (or several) question(s) can

systematically affect answering behavior in subsequent questions. We test this intuition in

three controlled survey studies. All surveys consisted of one main question of interest and

one (or several) additional question(s) that was (were) asked beforehand. We randomly

varied whether the additional questions were included in the survey or not. The three

surveys were designed to cover typical topics studied in many surveys. The first survey

elicited attitudes towards a political/moral question (the punishment of a murderer). The

second survey asked for the degree to which participants followed social norms (in the

context of lying behavior). Finally, the third survey was about general well-being and

life satisfaction.2

Our results show a significant impact of the additional question(s). Inclusion or exclusion affects responses to the question of interest in a systematic way. We find that

our manipulation reduced the number of people that agreed that a murderer should be

imprisoned for the rest of his life by more than 20 percentage points. In the context of

lying, we show that including one additional question reduces self-reported lying behavior

by about 11 percent. Responses to our question on life satisfaction are systematically

1

Parts of the data and the theoretical framework presented here are taken from or built on Falk and

Zimmermann (2012a and 2012b).

2

For overviews on research about happiness and life satisfaction, see for example Oswald (1997), Frey

and Stutzer (2001) or Layard (2005).

2

affected as well. Asking several related questions before asking about life-satisfaction

increases stated satisfaction by about 7 percent. These effects are large and important

from a methodological perspective. They show how malleable survey responses are towards rather subtle changes in survey design: the inclusion of only one additional survey

question can have a substantial effect on response behavior in subsequent questions. Our

findings add to the literature on survey methodology, in particular to the literature on

so-called context effects, that arise from asking several related questions and question ordering (see Tourangeau (1999)). Two main effects are distinguished, contrast effects and

assimilation effects. Contrast effects describe negative correlations between previously

asked and current questions while assimilation effects describe positive correlations (see

for example Schwarz et al. (1991)). The main method to analyze these effects is known as

split-ballot experiments (see for example Groves et al. (2009)). Our paper contributes to

this literature by providing a simple formal argument as well as experimental evidence on

how a particular behavioral pattern, the desire for consistency, affects survey responses

when several related questions are asked in a systematic way. In particular our findings

underscore that the direction of consistency effects is predictable and show how they

can bias, or even be misused to manipulate response behavior in surveys. In addition,

our findings, in concert with related studies, show that effects of inclusion of additional

questions will be particularly severe, if image concerns of respondents are high.3

Our work is also related to a large literature in social psychology. Cialdini (1984)

has put forward the idea that consistency is a signal of strength. “It is at the heart of

logic, rationality, stability and honesty” (Cialdini (1984)). Cognitive dissonance theory

offers a different explanation for consistency preferences as consistent behavior helps

people to avoid cognitive dissonances. The first theoretical foundation of that concept is

developed in Heider (1946), Newcomb (1953) and Festinger (1957). Yet another potential

explanation for a taste for consistency can also be found in Cialdini (1984), i.e., costs of

thinking. If thinking is costly, consistent behavior offers a straightforward way to avoid

these costs. In this paper we simply assume a taste for consistency, remaining ignorant

about its roots. A number of studies examine the potential of consistency preferences

to influence behavior. Famous examples are Freedman and Fraser (1966) and Sherman

(1980) who analyze the effectiveness of the so called foot-in- the-door technique in different

experiments. Cialdini et al. (1978) examine how the taste for consistency can be used to

influence behavior via another channel, the so-called low-ball procedure. This technique

3

This last point is discussed in more detail in section 4.

3

aims to gain commitment to an action by not fully revealing its true consequences, for

example costs. After commitment is reached, true consequences are revealed but the

desire to appear consistent makes people stick to their commitment.

In the economics literature Falk and Zimmermann (2012a) have argued that there

exists a rational signaling motive for behaving consistently. They show theoretically and

experimentally that consistency of actions or statements is a signal of skill, personality

or identity. If people understand the informativeness of consistency as a signal of positive traits, they should value consistency of others. In anticipation of this value decision

makers should use consistency as signaling device. Falk and Zimmermann (2012b) conduct a series of experiments that underscore the importance of consistency for economic

behavior. Eyster (2002) and Yariv (2005) have put forward models of consistent choice.

In Eyster (2002) people try to rationalize past mistakes by taking current actions that

justify these mistakes, thereby reducing cognitive dissonances. Yariv (2005) proposes a

model where people reduce cognitive dissonance by sticking to beliefs under which past

choices were optimal. Ellingsen and Johannesson (2004) and Vanberg (2008) refer to the

taste for consistency as a possible reason for why lying entails costs.

In the next section we present a simple reduced-form model that allows us to develop

predictions for our survey studies. Section 3 contains the design and results of our survey

studies and section 4 concludes.

2

The Model

We present a simple binary model that is a reduced-form of the model developed in Falk

and Zimmermann (2012a). In the model we consider survey response behavior in two

situations, one where a prior, related question is asked and one where no prior question

is asked.

2.1

Set-up

In period t, decision-makers (D) choose xt from a binary choice set X = {Red, Blue}, e.g.,

answering a survey question. D has a true underlying opinion µ ∈ X. However, in the

beginning decision-makers are holding an uninformative prior on µ, i.e., P r(µ = Red) =

P r(µ = Blue) = 21 . This reflects that, before reading the actual question, decision-makers

have no prior knowledge about the decision context they will be facing. After reading the

question, decision-makers learn something about the context of the survey and thus about

4

their true underlying opinion µ. This “contextual” information is captured by a signal

mt about µ. Signals are of strength pt , i.e., pt = P r(mt = Red|µ = Red) = P r(mt =

Blue|µ = Blue). We assume that

1

2

< pt < 1. Thus signals are informative, but

decision-makers do not perfectly learn µ, i.e., we assume some preference uncertainty.

Many survey questions are inherently difficult to answer. We therefore argue that it

is plausible that decision-makers do not always act according to their true underlying

opinion. Similarly, imperfect knowledge about µ could be interpreted as simple mistakes.

The source of mistakes could lie in the process of thinking about the best alternative.

Cognitive resources are limited and consequently mistakes in determining the preferred

answer are likely.

Upon receiving a signal mt , D updates beliefs about µ following Bayes’ rule. Throughout the paper l(mt ) denotes D’s beliefs about µ in terms of the probability she assigns on

Red being her opinion conditional on mt , i.e., l(mt ) = P r(µ = Red|mt ). Since the prior

on µ is uninformative, D’s belief is completely determined by the signal she received in

period t, mt .

Decision-makers choose xt in order to maximize utility. D’s utility function consists

of two components. The first is “standard” outcome-based utility. In the survey context,

standard utility captures an intrinsic preference to answer questions truthfully, i.e., to

state the true opinion, attitudes, estimates etc. Standard utility is 1 if D chooses xt = µ

and 0 otherwise. Decision-makers also care about making consistent choices. The taste

for consistency is captured by a function β() that can take on two values, βH and βL with

βH > βL . The function has two arguments, the actual choices xt and the choice history

xh . The choice history consists of all past choices that are related to the actual choice

xt . In the survey context these are related questions that cover a similar topic or that

are somehow connected with xt . For simplicity, to facilitate the definition of consistency

we assume that xh ∈ {Red, Blue}. The function takes on the value βH if xt and xh are

consistent and βL otherwise. In sum, the taste for consistency is described as follows:

β(xt , xh ) =

βH

if xt = xh

βL

otherwise.

If no choice history exists, we assume that consistency is irrelevant.4

4

Note that we abstract here from effects of the presence of an audience for behavior. In the original

model by Falk and Zimmermann (2012a) the driver of consistent behavior is that it allows the signaling

of skills towards others. This could easily be incorporated in our set-up by introducing an additional

parameter in our function β() that captures the strength of the taste for consistency depending on the

5

Now consider response behavior in our two situations of interest: in both situations

decision-makers make a choice xt and prior to that receive a signal mt . However, in one

situation a prior, additional question is asked and in the other no such question is asked.

In situations where a prior, related question is asked, i.e., where a choice history exists,

expected utility in period t conditional on xh is given by

E(Ut (xt )) =

l(mt ) ∗ 1 − β(Red, xh )

if xt = Red

(1 − l(mt )) ∗ 1 − β(Blue, xh ) if xt = Blue.

Suppose without loss of generality that in both situations, decision-makers receive a

signal mt = Blue. Thus, in principle, decision-makers in both situations should choose

xt = Blue. Now assume that in the prior, additional questions, the decision-maker has

chosen xh = Red. The discrepancy between the choice history and mt could simply reflect

some degree preference uncertainty. However, the discrepancy could also be systematic.

It could be due to biased responses to the prior question. In the survey context, a

bias can result from, e.g., social desirability (to appear more fair, cooperative or just

than is actually the case), or a desire to not reveal a particular political view or value.

Furthermore, biased responses can arise from the way questions are posed, e.g., the

framing of the question, or the degree of specificity. Also priming effects are possible.

Given the choice history, the decision-maker faces a trade-off between standard utility

and a desire for consistency. If βH is sufficiently larger than βL , the decision-maker will

choose to act consistently with her choice history by selecting xh = Red. If no prior

question is asked there exists no choice history. Therefore, the decision-maker is not

constrained by consistency concerns and will simply choose xh = Blue.

This is stated more precisely in the following Proposition:

PROPOSITION: Assume w.l.g. that xh = Red. If consistency concerns are sufficiently

large, i.e., βH − βL ≥ 1 − 2 ∗ l(mt = Blue), decision-makers in period 2 always choose

consistently x∗t = xh = Red. In the absence of a choice history instead, xt = Blue is

chosen.

Thus, choices in situations where a choice history exists may differ from choices in

identical situations absent a choice history. If past decisions were biased, this bias will

carry over to subsequent choices due to the desire to act consistently.

presence, size etc. of an audience. Then, higher image concerns would lead to larger effects on response

behavior.

6

3

Survey Manipulation

3.1

Design

We wanted to examine how the inclusion of related additional questions can affect response behavior in a survey. We designed three survey studies where we selected three

important topics: political/moral attitude, norm compliance and life-satisfaction.

The basic design of all three survey studies was very simple. We always study two

conditions which were randomly varied between subjects. In the control condition, subjects only had to answer our main question of interest. In the manipulation condition,

subjects had to answer one or several related questions before they had to answer our

main question of interest. The questions were as follows:

Survey 1 - Punishment of a murderer: In survey 1, our main question of interest

was if subjects would agree that a murderer should be imprisoned for the rest of his life.

Subjects were asked to read a short text that described a horrible deed of a murderer.

After reading the text, subjects were asked to answer the following question: “Do you

agree with the following statement? I would approve if the offender would be sent to

prison for the rest of his life, never to be released.” Subjects could either agree or disagree

with the statement by checking the appropriate box. In the manipulation treatment,

subjects had to answer a different but related question first, namely: “Do you agree with

the following statement? Everybody deserves a second chance in life. Even dangerous

criminals should be released after their imprisonment and be given a chance to start a

new life.” Subjects could either agree or disagree.

Survey 2 - Lying behavior: In survey 2, we were interested in lying behavior.

We described to subjects a lying experiment similar to Fischbacher and Heusi (2011).

Subjects were told to imagine that they participated in an experiment where they were

paid according to the roll of a die. Subjects would roll a die in private and were then

paid according to the number they reported to the experimenter. A reported “1” would

earn them 2 Euro, a “2” would earn them 4 Euro and so on. Maximum earnings would

be 12 if a “6” is reported. Thus it was clear to our subjects that in the experiment there

were incentives to lie and report a high number. In the main question of this survey

we asked subjects hypothetically which number they would report if they participated

in such an experiment, conditional on the actual die roll. Thus we asked subjects which

number they would report if they rolled a “1”, what they would report if they rolled a

“2” etc. In the manipulation treatment we asked two additional questions before subjects

7

were explained the hypothetical lying experiment. Subjects were asked to which degree

they would agree with the following statements: (1) “I am an honest person”; (2) “Other

people can rely on my words”. Subjects could respond on a scale from 1 (“do not agree”)

to 5 (“completely agree”).

Survey 3 - Life-satisfaction: In survey 3 we asked subjects about their lifesatisfaction. Our main question of interest was: “How satisfied are you at present with

your life, all things considered?”. Subjects could respond on a scale from 0 to 10. In the

manipulation condition we asked several questions before the question on life-satisfaction.

Questions were about health condition, satisfaction with field of study, number of friends

and optimism about finding a good job after leaving university.5

Procedures: Subjects were mostly students from the University of Bonn and were

recruited using the software by Greiner (2003). All surveys were conducted using paper

and pencil at the BonnEconLab at the end of different and unrelated experiments.6

3.2

Hypothesis

The inclusion of additional questions in the manipulation conditions should trigger subjects’ consistency concerns when answering the respective main question of interest. If

responses to the additional questions are “biased” in a systematic way, the bias should

extend to the main question due to a desire to act consistently. Consequently, responses

to the main question of interest should systematically differ between manipulation and

control question in all our studies.

To illustrate this in more detail, consider survey 1. Here we expected that most

subjects in the control group would agree with the statement that the murderer should

be imprisoned forever. We also expected that many subjects in the manipulation group

would agree with the statement that everybody deserves a second chance. Therefore our

hypothesis is that subjects in the manipulation group would feel a desire to be consistent

with their first response and therefore agree less frequently with the statement that the

murderer should be imprisoned forever, as compared to the control treatment.

HYPOTHESIS: In all three surveys, responses to the main question of interest differ

significantly between the manipulation and the control condition, in the direction

5

In the control condition we actually asked the additional questions as well, but after subjects had

answered the question on life-satisfaction.

6

One of the experiments was a simple bargaining experiment, the other was a real effort experiment designed to analyze effects of various personality traits and gender on effort provision. Note that

our treatment conditions were always randomized within session, such that no interactions with the

treatments of the experiments that were conducted beforehand are possible.

8

predicted by concerns for consistency.

3.3

Results

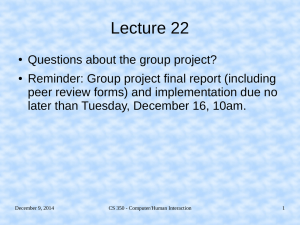

Survey 1: A total of 95 subjects participated in survey 1. Figure 1 summarizes our

results. We first analyze how many subjects in the control treatment agreed that the

murderer should be sent to prison for the rest of his life. Given the horrible deed of the

murderer, we expected that most subjects would agree. It turns out that 44 out of 48

subjects (91.7 percent) responded with “I agree”. Now consider how many subjects in

the manipulation treatment agreed with the statement that everybody deserves a second

chance in life. Here we expected that many subjects would agree to give a second chance.

This it what we find: 26 out of 47 subjects (55.3 percent) responded with “I agree”.

Second Chance in Life?

Imprison Murderer Forever?

100

90

Relative Frequency

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Manipulation Treatment

Control Treatment

Figure 1: Relative frequencies of statement “Yes” for question on punishment of murderer for manipulation and control treatment plus relative frequency of statement “Yes” for question on second chance in

life (only manipulation treatment).

Given these results, the model predicts that in order to be consistent with the statement that everybody deserves a second chance, fewer subjects in the manipulation treatment agree to imprison the murderer forever. This is confirmed by our data. Only 32 out

of 47 subjects (68.0 percent) stated that they would approve if the offender would never

live in freedom again. Thus the approval rate dropped from 91.7 percent in the control

treatment to 68.0 percent in the manipulation treatment. This difference is statistically

significant using either a Fisher exact test (p-value < 0.005) or simple Probit regression,

regressing a dummy variable for “agree” or “disagree” on a constant and a treatment

dummy (p-value < 0.005). Thus, we were able to significantly manipulate reported attitudes towards the punishment of a murderer, simply by including an additional question.

9

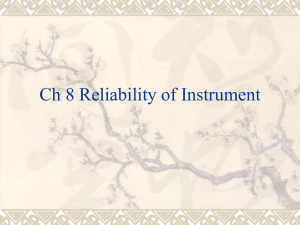

Survey 2: 68 subjects participated in survey 2. First, consider responses to the

two questions on honesty we asked in the manipulation treatment. We expected that

a very high number of subjects would state to be honest. This is indeed what we find.

86 percent of subjects either agreed or completely agreed with the statement “I am an

honest person”. For the statement “Other people can rely on my words” all subjects

either agreed or completely agreed.

Manipulation Treatment

Control Treatment

Reported Dice Roll

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

1

2

3

4

Actual Dice Roll

5

6

Figure 2: Average reported and actual die roll for manipulation and control treatment.

Given this very high degree of self-reported honesty, we expected that subjects would

lie less in the hypothetical lying experiment compared to the control treatment, in order

to be consistent with prior statements of being honest. This is confirmed by our data.

When we use the sum of all reported dice rolls (six reports, one for each possible die roll)

as our measure of hypothetical lying behavior, we find that subjects in the manipulation

treatment report a sum of 24.43 on average. Reported dice rolls in the control treatment

are on average 3.07 points higher. This difference is significant using a Ranksum test

(p-value < 0.01) or OLS, regressing reported dice rolls on a constant and a treatment

dummy (p-value for treatment dummy = 0.02).

Figure 2 provides a more detailed description of self-reported lying behavior. It displays the average reported die roll conditional on the actual die roll for both treatments.

We see that, at all levels, reports in the manipulation treatment are below those in the

control treatment. For example, if the actual die roll was a one, subjects in the control

treatment on average indicate a report of almost 3.5. The corresponding average report

in the manipulation treatment is more than one point below.7 The difference between

7

Note that Figure 2 also reveals that (hypothetical) lying behavior does not vanish in the manipulation

treatment. Average reported dice rolls in the manipulation treatment are always above the actual die

10

the two treatments gets smaller for higher actual die rolls. This makes sense, as the scope

for lying gets smaller. There is, for instance, no point in lying and reporting a number

below 6 if the actual die roll is 6.

Survey 3: A total of 180 subjects participated in survey 3. The average stated lifesatisfaction over both treatments on a Likert scale from 0 to 10 was 7.32. If we compare

stated subjective life-satisfaction between the treatments, we find that life-satisfaction is

.48 points higher in the manipulation treatment (when questions about health, number

of friends etc. were asked before). The median (modal) response in the manipulation

treatment was 8 (9), while the median (modal) response in the control condition was 7

(8). The difference between treatments is significant using a Ranksum test (p-value <

0.05) or OLS, regressing happiness on a constant and a treatment dummy (p-value for

treatment dummy < 0.1).

4

Concluding Remarks

In this paper we showed how a taste for consistency can systematically influence response

behavior in surveys. In three different surveys, we demonstrated that the inclusion of

one or several questions affects answers to subsequent related questions in a systematic

and predictable way. Our results underscore the importance of a taste for consistency as

a means of influence and highlight the fragility of response behavior.

We demonstrated similar patterns of results in three different examples. These examples varied from more quantitative measures such as the questions on life satisfaction

elicited with the widely used Likert scale, to more qualitative measures such as attitudes

towards the punishment of a murderer which were elicited with a simple yes or no format.

In this sense, our data suggest that the consistency bias carries over to all types of survey

questions.

Our findings reveal that response behavior should be interpreted with caution. Questions about life-satisfaction or support for certain political statements can be extremely

volatile, depending on survey design. In one survey we were able to manipulate the number of people that agreed that a murderer should be imprisoned for the rest of his life

by more than 20 percentage points, simply by adding one additional question. With a

similar manipulation we increased stated subjective life-satisfaction by about 7 percent.

This suggests that survey results should always be read and interpreted taking possible

roll. (Reported dice rolls conditional on an actual die roll of six being the natural exception.)

11

interdependencies with other questions into account. For comparisons of survey results

between different groups, across countries, or over time it is crucial that not only the main

question of interest, but also all other questions asked in the survey should be identical

and/or randomized across groups, countries or over time.

While we do not show this explicitly in this paper, results from a previous study

suggest that consequences of a taste for consistency will be particularly severe if image

concerns of participants are high (see Falk and Zimmermann (2012a)). Thus, consequences of a taste for consistency for survey responses are likely to be more pronounced

when the survey is conducted in face-to-face interviews compared to surveys conducted

via telephone or mail.

12

REFERENCES

Cialdini, Robert. 1984. “Influence, the Psychology of Persuasion.” New York:

Harper Collins.

Cialdini, Robert, Rodney Bassett, John Cacioppo and John Miller. 1978.

“Low-Ball Procedure for Producing Compliance: Commitment then Cost.” Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(5): 463-476.

Ellingsen, Tore and Magnus Johannesson. 2004. “Promises, Threats and Fairness.” The Economic Journal, 114(April): 397-420.

Eyster, Erik. 2002. “Rationalizing the Past: a Taste for Consistency.” working paper.

Falk, Armin and Florian Zimmermann. 2012(a). “Consistency as a Signal of

Skills.” working paper, University of Bonn.

Falk, Armin and Florian Zimmermann. 2012(b). “Consistency Preferences and

Commitment: Implications for Behavior.” working paper, University of Bonn.

Festinger, Leon. 1957. “A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.” Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press.

Fischbacher, Urs and Franziska Heusi. 2008. “Lies in Disguise: An Experimental

Study on Cheating,” TWI Research Paper Series, 40.

Freedman, Jonathan and Scott Fraser. 1966. “Compliance Without Pressure:

The Foot in the Door Technique.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

4(2): 195-202.

Frey, Bruno and Alois Stutzer. 2001. “Happiness and Economics: How the Economy and Institutions Affect Human Well-Being.” Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton

University Press.

Greiner, Ben. 2003. “An Online Recruitment System for Economic Experiments.”

In Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen 2003. GWDG Bericht 63, ed Kurt

Kremer and Volker Macho, pp. 79-93. Goettingen: Ges. fuer Wiss. Datenverarbeitung.

13

Groves, Robert, Floyd Fowler, Mick Couper, James Lepkowski, Eleanor

Singer, and Roger Tourangeau. 2009. “Survey Methodology.” 2nd Edition.

Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Heider, Fritz. 1946. “Attitudes and Cognitive Organization.” Journal of Psychology,

21: 107-112.

Layard, Richard. 2005. “Happiness: Lessons From a New Science.” London, Penguin

Books.

Newcomb, Theodore. 1953. “An Approach to the Study of Communicative Acts.”

Psychological Review, 60: 393-404.

Oswald, Andrew. 1997. “Happiness and Economic Performance.” The Economic

Journal, 107: 1815-1831.

Schwarz, Norbert, Fritz Strack and Hans-Peter Mai. 1991. Assimilation and

Contrast Effects on Part-Whole Questions Sequences:A Conversational Logic Analysis.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 55, 3-23.

Sherman, Steven. 1980. “On the Self-Erasing Nature of Errors of Prediction.”

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(2): 211-221.

Tourangeau, Roger. 1999. “Context Effects on Answers to Attitude Questions.”

In Cognition and Survey Research, edited by M. G. Sirken, D. J. Herrmann, S.

Schechter, N. Schwarz, J. M. Tanur, and R. Tourangeau. New York: John Wiley

and Sons Inc.

Vanberg, Christoph. 2008. “Why Do People Keep Their Promises? An Experimental Test of Two Explanations.” Econometrica, 76(6): 1467-1480.

Yariv, Leeat. 2005. “I’ll See it When I Believe it - A Simple Model of Cognitive

Consistency.” working paper.

14