Rounding of Amounts of VAT - Empowered Committee of State

Articles

Joep Swinkels*

Rounding of Amounts of VAT

Half a year ago, the Dutch Supreme Court referred preliminary questions to the European

Court of Justice on the rounding of amounts of

VAT due. Although the issue may seem to be, and probably is, trivial to most businesses, it is of interest to some categories of businesses. In this article, the author briefly describes the background, issues and relevance of the case.

1. Introduction

On 27 November 2006, the Dutch Supreme Court referred preliminary questions to the European Court of

Justice in Ahold 1 on the rounding of amounts of VAT due. This article briefly describes the background, issues and relevance of the case.

2. Effect of Rounding

2.1. Calculation of VAT due

The method of calculation of the VAT due on transactions consisting of more than a single good or service has at least two aspects that are relevant in the context of this case. In the first place, the question arises of whether the VAT due must be calculated on the basis of:

– each individual unit of the supply;

– each category of identical units, i.e. per line of the invoice;

– each category of units subject to the same VAT regime or rate; or

– the total transaction, i.e. on the basis of the total value of the basket of goods and services (per invoice).

Since the smallest unit in which amounts of money can be expressed is the cent, that question is of importance to determine at what stage the amount of VAT due must be rounded. The larger the number of occasions on which rounding takes place, the larger its total effect.

In the second place, the question arises of what method of rounding must or may be used, i.e. must the amount of VAT due be rounded on the basis of the mathematical method or may it be rounded consistently to the advantage of the supplier, i.e. rounded down to the smallest unit of currency. Under the mathematical method, amounts of money are rounded on the basis of the third decimal digit: where that digit is 0, the final amount is determined by leaving out the third and following decimal digits, where the third decimal digit is 1, 2, 3, or 4, the final amount is rounded down to the last whole eurocent, and where the third decimal digit is 5, 6, 7, 8 or 9, the amount is rounded up to the next whole eurocent.

It is clear that the mathematical method is slightly to the disadvantage of the taxable person because taking a calculation of three decimal digits, there are four fractions

(where the third decimal digit is 1, 2, 3, or 4) which lead to rounding down, and five fractions (where the third decimal digit is 5, 6, 7, 8 or 9) which lead to rounding up.

Although those issues may seem trivial, the results of the various methods may lead to significant differences in the total amount of VAT, in particular where the taxable person supplies large quantities of different goods at relatively low unit prices to a large number of different customers every day, for example, supermarkets, telecommunications companies, suppliers of water, electricity and gas, petrol stations, etc.

For example, a supermarket supplies the following basket of goods to a customer at the following listed prices, i.e. inclusive of 6% VAT:

1 loaf of bread

1 pack of coffee

1 carton of milk

1 pack of sugar total value

EUR 1.39

EUR 3.09

EUR 0.79

EUR 1.49

EUR 6.76

On the assumption that the supermarket accounts for

VAT on the basis of cash receipts, 2 the supplier will normally calculate the amount of VAT due on the basket of goods by extracting the VAT element from the total amount he receives from the customer, i.e. EUR 6.76. The amount of VAT due at the rate of VAT of 6% is EUR 6.76

x 6/106 = EUR 0.3826, which is rounded to EUR 0.38.

However, if he were to calculate the VAT due per separate unit of the supply and depending on the method of rounding, the VAT due would have been EUR 0.37 (on the basis of mathematical rounding) and EUR 0.36 (on the basis of the rounding-down approach):

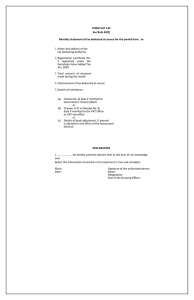

Goods VAT due per unit Rounding per unit mathematical down bread 6/106 x EUR 1.39 = 0.0786791

0.08

coffee 6/106 x EUR 3.09 = 0.1749054

0.17

milk 6/106 x EUR 0.79 = 0.0447169

0.04

sugar 6/106 x EUR 1.49 = 0.0843395

0.08

total 0.37

0.07

0.17

0.04

0.08

0.36

* Tax adviser for KPMG Meijburg & Co, Amsterdam.

1.

Fiscale eenheid Koninklijke Ahold NV v. Staatssecretaris van Financiën ,

Case C-484/06, OJ C 20/11 of 27 January 2007.

2.

Technically, accounting for VAT on the basis of cash receipts only means that VAT is due at the time the supplier receives payment for the goods or services from his customer; it does not necessarily mean that the VAT due is determined by extracting the amount of VAT from the total amount received.

Cash-based accounting has the advantage that it avoids the need for adjustments to the VAT due on account of bad debts.

INTERNATIONAL VAT MONITOR MARCH/APRIL 2007

113

© IBFD

Articles

On the basket of four goods, the difference is EUR 0.01

and EUR 0.02, respectively, which is not much. However, on the basis of thousands of transactions per day, and six or seven days per week, the total difference per month may be considerable.

2.2. Proceedings of Ahold

The VAT group Koninklijke Ahold (Ahold) is an international enterprise operating in the food sector. It operates dozens of supermarkets and initially calculated the

VAT due on its supplies by extracting the total amount of VAT from the total amount received from its customers relating to separate baskets of standard-rated, 3 reduced-rated 4 and non-taxed 5 goods. In October 2003,

Ahold reprogrammed its cash registers in two supermarkets and recalculated the VAT due on the basis of separate calculations for each line of the invoice

(receipt), rounding down each individual amount. The result of that recalculation was a reduction of its VAT liability for that month by EUR 1,441. However, the tax authorities refused Ahold’s refund application.

Ahold claimed that use of the mathematical method of rounding amounts of VAT would lead to a liability which was higher than the applicable rate of 6% of the consideration. For example, where the listed price, i.e.

the price inclusive of VAT, for a good is EUR 0.27, the

VAT due at the rate of 6% is EUR 0.0152826. If that amount were rounded mathematically to EUR 0.02, the effective rate would be 8%, 6 instead of 6%. On the contention that payment of VAT at a higher rate than that prescribed is in violation of Community law and unconstitutional, Ahold concluded that amounts of VAT must be rounded down under all circumstances. The tax administration took the view that the mathematical method of rounding must be followed for VAT purposes, just like amounts expressed in the former national currency had to be converted into euro on the basis of mathematical rounding.

7

The court of first instance, the Tax Court Amsterdam, 8 observed that amounts of VAT must be expressed in the currency of the country concerned, which is the euro for the Netherlands. The smallest possible unit in which amounts of VAT can be expressed is the eurocent. Where the rate of VAT applicable to goods and services is expressed as a percentage of the taxable amount, it is inevitable that the final result will often include a fraction of a eurocent. Under those circumstances, the amount of VAT must be rounded following the mathematical method because that method is the most obvious alternative. In this respect, the Tax Court noted that, where taxable persons are entitled to follow a more advantageous method of rounding, the national or

European legislation expressly indicates so.

9 Since Ahold and the tax administration did not disagree as to the principle that VAT is due on the separate elements of the supply, the court did not take a position as regards that issue.

Op 19 May 2005, the Advocate General of the Dutch

Supreme Court delivered his Opinion in this case, in

114

INTERNATIONAL VAT MONITOR MARCH/APRIL 2007 which he made several comments on the decision of the

Tax Court. The Advocate General disagreed that the

VAT due must be determined on the basis of the separate elements of the supply. He concluded that the later the stage at which amounts of VAT are rounded, the more precise the VAT liability is calculated and the principle that the amount of VAT must be proportional to the total price is observed. According to the Advocate

General, amounts of VAT must be rounded on two occasions. Firstly, at the time of issue of the invoice; on that occasion, rounding must take place on the basis of the total amount subject to a specific VAT rate or regime.

Rounding will necessarily produce a certain degree of imprecision, which is not a problem where the customer is entitled to deduct the amount of VAT that is mentioned on the invoice and remitted by the supplier to the authorities. Rounding the amount of VAT at that stage does not significantly affect the amount of VAT borne by final consumers.

The second stage of rounding happens when the taxable person must remit the VAT due for the tax period to the authorities, i.e. the time of filing the periodic VAT return.

In most cases, rounding the amount of VAT is only necessary at the second stage because, under Dutch law, the total amount of VAT due for the tax period may be rounded down to the next whole euro. It should be noted that the Advocate General did not express his opinion on the method of rounding to be used.

In my view, the Advocate General ignored the fact that, in practice, taxable persons issue an invoice or specified receipt, even if the issue of an invoice is not compulsory, in order to formalize the amount of VAT due. Mentioning an amount of VAT on an invoice should imply that that VAT is remitted to the authorities.

The Dutch Minister of Finance did not take any chances as regards the outcome of the judicial proceedings and

3.

For example, alcoholic beverages and most non-food items.

4.

For example, food, magazines and newspapers.

5.

For example, manufactured tobacco, which is subject to VAT under the banderol system, i.e. VAT on the retail price is paid at the time the goods are released from control of the excise duty authorities.

6.

Since the mathematically rounded amount of VAT due at the rate of 6% on a good with a tax-inclusive price of EUR 0.27 is EUR 0.02, the consideration is EUR 0.25 and the effective VAT rate is 0.02/0.25 = 8%. Where, under the same circumstances, the tax-inclusive price is EUR 0.09, the effective VAT is in fact 12.5%. On the other hand, where the tax-inclusive price is EUR 0.26, the effective VAT rate is only 4%.

7.

Art. 5 of Council Regulation (EC) No. 1103/97 of 17 June 1997 on certain provisions relating to the introduction of the euro, OJ L 162, provides that monetary amounts to be paid or accounted for when a rounding takes place after a conversion into the euro unit must be rounded up or down to the nearest cent. Monetary amounts to be paid or accounted for which are converted into a national currency unit must be rounded up or down to the nearest subunit or in the absence of a subunit to the nearest unit, or according to national law or practice to a multiple or fraction of the subunit or unit of the national currency unit. If the application of the conversion rate gives a result which is exactly halfway, the sum must be rounded up.

8.

Decision of the Tax Court Amsterdam of 16 August 2004, No.

P04/00224.

9.

For example, under Art. 19(1) of the Sixth Directive (Art. 175(1) of Directive 2006/112), the pro rata is rounded up to a figure not exceeding the next whole number.

© IBFD

issued a Royal Decree, 10 which prescribes that, with effect from 1 July 2004, amounts of VAT due on the consideration or customs value must be rounded mathematically to the next whole cent. The Decree does not indicate whether the “consideration” is the consideration for the total supply or for the separate elements of the supply.

In the course of the subsequent proceedings in Ahold , the Supreme Court asked the ECJ whether the rounding of VAT amounts is governed solely by national law or is a matter for Community law. In this respect, the

Supreme Court particularly referred to the first and second paragraphs of Art. 2 of the First Directive 11 and Art.

11(A)(1)(a) and Art. 22(3)(b), first sentence, (version as at 1 January 2004) and (5) of the Sixth Directive.

12 If the rounding is governed by Community law, the Supreme

Court also wished to know whether it follows from the aforementioned provisions of the Directives that the

Member States are required to permit rounding down per article, even if different transactions are included in one invoice and/or one tax return.

3. Comments

The questions referred to the ECJ by the Dutch Supreme

Court in Ahold give rise to the following comments as regards the possible effects of rounding, the legal basis on which rounding should take place, the neutrality of the VAT system and the concept of the unit of the supply.

3.1. Effects of rounding

The issue raised in Ahold may be of no importance to most taxable persons; the answer of the ECJ to the

Supreme Court’s questions may however be of great importance to certain categories of taxable persons, in particular those supplying large numbers of goods or services to large numbers of customers at relatively low listed prices per unit. If the ECJ were to decide that the total amount of VAT due on the supply is the total sum of VAT due on the individual elements of the supply

(which is not included in the questions referred on that occasion), and if that VAT were to be rounded down under all circumstances, certain categories of suppliers would be able to escape from paying VAT if the value of the units of their supplies is sufficiently low. In this respect, it should be borne in mind that, at a VAT rate of

6%, a listed unit price of EUR 0.17, would result in a rounded-down VAT liability of zero. Under the method of mathematical rounding, the same result is limited to listed unit prices of EUR 0.08 or less (6/106 x EUR 0.08

= EUR 0.004). It would therefore be tempting for, for example, telecommunications companies, to define their services in terms of sufficiently small units.

3.2. Legal basis for rounding

According to the Dutch Ministry of Finance, the European Commission takes the view that the method of rounding amounts of VAT is a matter for which, under the principle of subsidiarity, the Member States must set the rules.

13 The principle of subsidiarity is based on the

© IBFD

Articles second paragraph of Art. 5 of the EC Treaty, 14 which provides that, in areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Community must take action only if, and in so far as, the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States and can therefore, by reason of the scale or effects of the proposed action, be better achieved by the Community.

However, since the Community legislation on VAT is aimed at founding a common system of VAT, and rounding amounts of VAT directly affects the liability to pay

VAT, this matter should not be left to the Member States.

It is not, for example, a measure in the framework of the collection of the tax. It forms part of the common system of VAT and should therefore be included in the

Community legislation. In this respect, it should be noted that the method of rounding of amounts of VAT to be reported and remitted by non-EU service providers rendering electronic services to EU non-taxable customers under the special scheme laid down by

Art. 26c of the Sixth Directive 15 is not basically different from the rounding of amounts of VAT by other taxable persons under different circumstances. As regards the rounding, or rather non-rounding, of amounts of VAT due by the former category of service providers, the VAT

Implementing Regulation 16 already contains specific rules.

17

10 .

Royal Decree of 11 June 2004 amending the Uitvoeringsbesluit omzetbelasting 1968 (Implementing Decree Turnover Tax 1968), Official Journal 2004,

267, see the new Art. 5a of the Implementing Decree.

11.

First Council Directive (227/67/EEC) of 11 April 1967 on the harmonization of legislation of Member States concerning turnover taxes (OJ, English Special Edition 1967, p. 14). The first and second paragraphs of Art. 2 read as follows:

The principle of the common system of value added tax involves the application to goods and services of a general tax on consumption exactly proportional to the price of the goods and services, whatever the number of transactions which take place in the production and distribution process before the stage at which tax is charged.

On each transaction, value added tax, calculated on the price of the goods or services at the rate applicable to such goods or services, shall be chargeable after deduction of the amount of value added tax borne directly by the various cost components.

12.

Sixth Council Directive (388/77/EEC) of 17 May 1977 on the harmonization of the laws of the Member States relating to turnover taxes – Common system of value added tax: uniform basis of assessment (OJ L 145, p. 1).

Under Art. 22(3)(b) of the Sixth Directive, inter alia, the following details must be mentioned on VAT invoices:

– the taxable amount per rate or exemption, the unit price exclusive of tax and any discounts or rebates if they are not included in the unit price;

– the VAT rate applied;

– the VAT amount payable, ... .

Art. 11(A)(1)(a) of the Sixth Directive provides that, in respect of supplies of goods and services, the taxable amount is everything that constitutes the consideration which has been or is to be obtained by the supplier from the purchaser, the customer or a third party for such supplies, including subsidies directly linked to the price of such supplies, and Art. 22(5) of the Sixth Directive provides that every taxable person must pay the net amount of the VAT when submitting the regular return.

13.

Explanatory Memorandum to the Royal Decree of 11 June 2004, see note 10.

14.

Consolidated version of the Treaty establishing the European

Community, OJ C 325/41 of 24 December 2002.

15.

Arts. 357 to 369 of Directive 2006/112.

16.

Council Regulation (EC) No. 1777/2005 of 17 October 2005 laying down implementing measures for Directive 77/388/EEC on the common system of value added tax, OJ L 288 of 29 October 2005.

17.

See Art. 20(4) of that Regulation, which provides that amounts on VAT returns made under the special scheme provided for in Art. 26c(B) of the

Sixth Directive (Arts. 346 and 347 of Directive 2006/112) must not be

INTERNATIONAL VAT MONITOR MARCH/APRIL 2007

115

Articles

As regards the form in which the rounding rules should be included in the Community legislation, it should be noted that adoption of a special collective measure under a collective authorization to be granted by the

Council to all Member States under Art. 395 of Directive

2006/112, for the purposes of achieving the goal that the

Member States apply a common policy to the rounding of amounts of VAT, does not provide a solution, even though such a measure would be within the objectives of that provision because it is aimed at preventing tax reduction, which could be considered to be a form of tax avoidance.

18 However, since the Community VAT legislation does not contain any rules on rounding amounts of VAT, adoption of a special measure is not a workable solution because it is impossible to deviate from a rule that does not exist. On the other hand, rules on rounding amounts of VAT could be added to the VAT Implementing Regulation, which already contains detailed rules on the amount of VAT payable by non-resident service providers rendering electronic services to European non-taxable customers.

3.3. Neutrality of the VAT system

The VAT itself must not be a burden to the taxable person who is liable to remit it to the authorities. On the other hand, VAT should equally not be a source of revenue to him. As regards the VAT itself, the taxable person’s position should be entirely neutral. From that principle, it follows that it would be unacceptable if the taxable person first charges a certain amount of VAT to his customer, subsequently recalculates that amount on the basis of different rules and, finally remits a lower amount to the authorities. That principle should not only apply where the taxable person charges the VAT to his customer on a VAT invoice, but also where he issues a receipt specifying the amount of VAT, or where he does not provide his customer with any specification of the amount of VAT charged to him, albeit that, in the latter circumstances it will be difficult to determine how large the VAT component actually is. Where he charges the

VAT due on supplies of goods or services to his customer on a VAT invoice, the supplier must mention that amount of VAT (rounded to whole cents) on the invoice under the tenth indent of Art. 22(3)(b) of the Sixth Directive and, under Art. 22(5) of the Directive, remit that amount to the authorities, not a recalculated lower amount.

3.4. Unit of the supply

It should be noted that the manner in which Ahold applied the rounding rules was not even the most extreme position. Ahold rounded the amount of VAT per line of the invoice/receipt. However, every line may contain several items. When a customer buys one loaf of bread, three packs of coffee, four cartons of milk and two packs of sugar, the total purchase may be shown on four lines, which means that the amounts of VAT are rounded on four occasions. More extreme was the initial position of Topps Tiles Plc (“Topps”).

19 Topps sold tiles and related goods mostly by retail. Its prices were advertised

116

INTERNATIONAL VAT MONITOR MARCH/APRIL 2007 as tax-inclusive amounts per tile. In 2003, Topps began to recalculate the VAT due on the basis of unit prices, i.e.

the price per tile, initially on the basis of the mathematical rule, which produced a reduction of its VAT liability in the order of GBP 8,600 per quarter. Later that year,

Topps applied the rounding method on the contention that only rounding down was required, which gave rise to reductions of VAT in the order of GBP 200,000 for each period. The tax authorities refused to refund the

VAT resulting from Topps’ recalculations.

Topps supplied tiles in any number and the price was quoted for a single tile so that, although they could well be supplied in a box containing 100, customers buying

100 tiles would know what each tile cost. Initially, Topps treated a supply of, say, 100 blue tiles of a particular type and 20 white tiles of a particular type as the supply of

120 separate goods and, accordingly, rounded the unit price 120 times. However, on the first day of the hearing which took place in the course of the proceedings before the Manchester Tribunal, Topps abandoned that extreme position and reduced its claim on the basis of the principle that each line of the invoice (receipt) was a separate supply of goods, i.e. the supply of 120 tiles above was treated as two separate supplies. Since the tax authorities agreed with that approach, the Tribunal did not have to rule on that aspect of the initial dispute. As regards the method of rounding, the Tribunal took the view that the mathematical method of rounding up and down more accurately achieved the result that the overall burden of VAT should be 17.5% of the value of the goods.

Unfortunately, the question of whether or not, and if so, to what extent, goods and services supplied as a “basket” must be treated as separate supplies of good and services was withdrawn from Topps and is not included in the questions referred to the ECJ in Ahold . The answer to that question will become particularly important should the ECJ decide that the VAT due on supplies must be rounded down in all circumstances. Under those circumstances, it will become important at what stage the amount of VAT due must or may be rounded. In other words, may or must a supply of a box of 100 tiles be treated as the supply of one good or 100 separate goods for the purposes of rounding the amount of VAT due?

Does the answer to that question depend on whether or not the total price for the box containing 100 tiles is equal to the price of 100 separate tiles? Must or may the supply of a six-pack of beer or a tray of 24 tins of soft drinks be treated as the supply of a single good? Is a tank load of gasoline the supply of a single good or the supply rounded up or down to the nearest whole monetary unit. The exact amount of

VAT must be reported and remitted.

18.

Art. 395(1) of Directive 2006/112 provides that the Council, acting unanimously on a proposal from the Commission, may authorize any Member State to introduce special measures for derogation from the provisions of this Directive, in order to simplify the procedure for collecting VAT or to prevent certain forms of tax evasion or avoidance.

19.

See Decision of the Manchester Tribunal of 15 August 2006 in Topps

Tiles Plc v. HM Revenue and Customs , No. 19751 .

© IBFD

of 50 separate litres of fuel? Is the supply of 260 telecommunications units per month the supply of a single service? Is the supply of three cartons of milk a single supply and does the answer to that question depend on whether or not the goods are mentioned on the same line or on separate lines of the related invoice/receipt? Does the supply of three reduced-rated bags of potato chips and two standard-rated six-packs of beer constitute a single supply, two separate supplies, or five or even more separate supplies? In other words, under what circumstances must or can “units of supply” and “prices per unit” be used to indicate supplies of separate goods or services, or do they merely serve as measures to determine the size or value of the total supply?

3.5. VAT invoices

In view of the fact that Art. 22(3)(b) of the Sixth Directive 20 prescribes that VAT invoices must, inter alia, show the taxable amount per rate or exemption, there are valid arguments for taking the view, just as the Advocate General of the Dutch Supreme Court has done and contrary to the views of the tax authorities in Ahold and

Topps , that, even where issue of a VAT invoice is not compulsory, the amount of VAT must be rounded in respect of the total value of the goods and services subject to the same VAT rate, and not earlier. After all, it should not make any difference whether taxable persons determine the amount of VAT due on their supplies on the basis of a compulsory invoice or on the basis of a practical method under which they extract the amount of VAT due from the total amount received in cash from their customers.

21 The mathematical method of rounding generally produces the best results, in that it achieves the aim that the effective rate of VAT applicable to the individual elements of the supply is equal to the statutory rate.

3.6. Moral aspects

Reduction of the burden of the tax after the supply has taken place by recalculation of the amount of VAT due on the supply also has a moral aspect. The supplier deceives his customers by suggesting that the VAT burden on the supply is higher than it actually is.

It is generally known that large groups of taxable persons use the tax system as an alibi to set their prices: when taxes go up, they immediately increase their selling prices and blame the government for the increase and, when taxes go down, their prices are not adjusted accordingly. As long as taxable persons actually remit to the authorities the same amount of VAT that they suggest to their customers is due on their supplies, their manipulative behaviour can be seen as part of the taxable persons’ freedom to set their selling prices at the level they choose. However, where the amount of VAT actually remitted to the authorities is different from the amount suggested to their customer, that behaviour gains a moral aspect. It is just as dishonest to provide customers, who are not entitled to input tax deduction, with invoices or receipts that show a higher amount of

© IBFD

Articles

VAT than that which is actually due, as it is to suggest to them that supplies are “tax-free”, whilst the supplier merely grants the customer a discount in the amount of the applicable VAT rate.

4. Conclusion

The questions referred to the ECJ in Ahold clearly indicate that taxable persons and their advisers continue the search for means and methods to reduce the burden of VAT. The ECJ has not accepted artificial schemes essentially aimed at obtaining a VAT advantage 22 but, although they may produce less spectacular results, there are various other ways of reducing the burden of the tax, such as rounding the amount of VAT due.

To my knowledge, taxable persons have not yet been successful in their contention that, due to the limitations and imperfections of the payment system, mathematical rounding of small amounts of

VAT may lead to the unlawful result that the effective VAT rate is higher than the statutory rate.

On the other hand, taxable persons cheerfully accept that, in different circumstances, mathematical rounding of amounts of VAT produces an effective VAT rate that is lower than the statutory rate, which is, strictly speaking, just as unlawful. The actual effect of the imperfections of the payment system is by definition negligible per individual transaction. However, the effect for the tax period may be considerable.

In my view, the questions referred to the ECJ in

Ahold may lead to a result that will encourage taxable persons to further explore the boundaries of the methods of reducing the amount of VAT due on their supplies by splitting them up into large numbers of separate supplies and consistently rounding down the VAT due on each individual fraction. The case shows that the time has come for the European legislature to more precisely indicate how the amount of VAT due on individual transactions must be determined, i.e. at what level amounts of VAT must be rounded. Since they have the same interest in putting an end to VAT manipulation, it should not be too difficult for the

27 Member States to adopt a common approach.

20.

Art. 226(8) of Directive 2006/112.

21.

See, inter alia, ECJ judgments of 27 October 1993 in Muys’ en de Winter’s

Bouw- en Aannemingsbedrijf v. Staatssecretaris van Financiën , Case C-281/91,

[1993] ECR I-5405, Para. 14, and of 8 July 1986 in Hans-Dieter and Ute

Kerrutt, Markgröningen v. Finanzamt Mönchengladbach-Mitte , Case 73/85,

[1986] ECR 2219.

22.

See the abuse-of-law doctrine in, inter alia, ECJ judgment of 21 February 2006 in Halifax plc, Leeds Permanent Development Services Ltd, County

Wide Property Investments Ltd v. Commissioners of Customs and Excise, Case

C-255/02, [2006] ECR I-1609.

INTERNATIONAL VAT MONITOR MARCH/APRIL 2007

117