Valuing Headquarters (HQs) - Affaires mondiales Canada

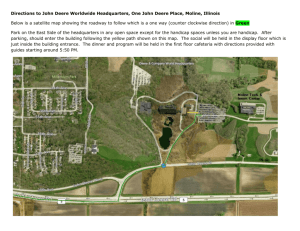

advertisement