economic evaluation: what is it good for?

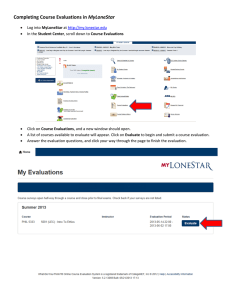

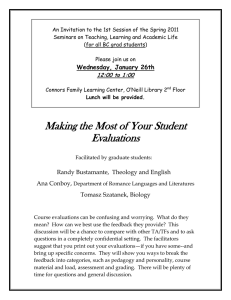

advertisement