Summary of Gallery Illumination: LED Lighting in Today`s Museums

advertisement

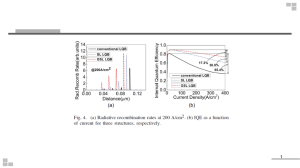

Summary of Gallery Illumination: LED Lighting in Today's Museums hosted by The Smithsonian American Art Museum on Friday, March 1st, 2013 Current and Past members of the Committee on Sustainable Conservation Practices (CSPC): Mary Elizabeth Haude, Jia-Sun Tsang, Mary Coughlin, Robin O’Hern and Patricia Silence The Smithsonian American Art Museum organized and presented a timely and informative conference on March 1st, 2013 titled “Gallery Illumination: LED lighting in Today’s Museums.” Light emitting diode (LED) lighting is a rapidly changing and clearly inevitable technology that demands that we learn new terminology and evaluation methods. Professionals responsible for exhibition lighting are currently confronted with big, expensive decisions. These are complicated by the fact that LED technology offers the possibility of a better (and/or different and/or worse) viewing experience than we are accustomed to. It also offers the likelihood of drastically reduced energy consumption (for light and building cooling), maintenance costs (changing light bulbs), and waste (in the form of spent bulbs and packaging). Expert lighting specialists, scientists, designers, and end-users generously shared expertise on the topic from their various perspectives. Descriptions of each are described below. Scott Rosenfeld, Exhibit Lighting Specialist at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), presented “How to Change a Light Bulb” that included information from a 2011 GATEWAY project with the U.S Department of Energy (DOE) to evaluate the effectiveness of LED retrofit lamps in museums. The LED lights can provide high quality of light, reduce connected load by up to 75%, and provide a return on investment (2 years in D.C.). Many incandescent lamps can be retrofitted to accept LED lights. Scott highlighted tools and metrics for selecting and evaluating LED products such as the spectral power distribution data, visual qualities, life cycle cost, and conservation risks and benefits. He found it difficult to find LED lamps for every lighting situation such as high intensity narrow LED lights or high lumen and high-intensity light for high ceiling galleries. Another challenge was finding compatible driver transformers and dimmers, which matters because incompatibility may result in flicker. LED lights also flicker as they burn out, which can be undesirable in gallery situations. A case study was presented on the use of retrofit PAR lamps for wall-washing and spot lighting for 20th Century Modern Galleries in SAAM. The 4000-hour lamp test has been completed, the 8000 hour and 12,000 hour tests are ongoing and will be added to the project report later. Jim Druzik, Senior Scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute, and Dr. Michael Royer, a Light Engineer at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory co-presented a talk entitled, “How safe is van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” to LED lighting? Quite safe, actually!" They provided advice to safeguard artwork from LED lighting, a rapidly maturing and evolving technology. They presented the damage potential of four LED lights, halogen, and filtered halogen. This presentation included the calculations and analysis of the relative damage potential of LEDs to dispel a recent misleading story in popular media about LED light damage to van Gogh’s “Sunflower” painting. The claim that typical museum LEDs can cause the same damage as seen in these accelerated aging studies has not been substantiated. They calculated the damage potential relative to the light source by multiplying the spectral power distribution with the damage function, which relates wavelength of light to amount of damage for a given material. They suggested that museums know the light-sensitivity of works of art in their collection or make best estimates based upon the literature. Naomi Miller’s presentation, “LEDs in Museums: They’re New and Cool and Cute, but Do They Really Save Money and Energy?” focused on four Department of Energy (DOE) GATEWAY Museum LED Demonstrations: Brooker Gallery, Field Museum, Chicago; University of Oregon, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Eugene; The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu; and The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. All four demonstration sites resulted in energy savings. The full reports for the four demonstrations are accessible at the DOE GATEWAY Studies site (http://www1.eere.energy.gov/buildings/ssl/gatewaydemos_results.html). For museums considering switching to LEDs, Ms. Miller stated that the cost and payback of LEDs in museums should be evaluated by the life cycle cost and not just the initial cost. In addition, she advised consulting the DOE LED Lighting Facts website (http://www.lightingfacts.com) for test data, working with a diversity of known, trusted LED brands, and proceeding slowly. An upcoming gateway project will combine control systems with LEDs. In his presentation, “What Colour Rendering Index (CRI, Ra) and Colour Temperature Actually Mean: Comparing Light Sources and Light Exposure at The National Gallery, London,” Mr. Padfield, the Senior Scientific Officer at the National Gallery, argued that museums should choose light metrics that provide information about the relative light damage potential to the art work. Lux levels provide the amount of light an artifact has been exposed to from a single light source relative to human perception, but are limited in the ability to establish color quality or intensity or in relating light to the sensitivity of the artwork. When considering different light sources for gallery illumination, comparing the SPD curves and the color quality scale (CQS) is recommended. SPD curves measure the entire array of light produced along the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Detailed information on SPD curves, Lux, correlated color temperature (CCT), color rendering index (CRI), color quality scale (CQS), and relative spectral sensitivity for various light sources can be found at the National Gallery, London site: http://research.ng-london.org.uk/scientific/spd. Additionally the site is interactive, allowing users to compare SPD curves of various light sources. Mr. Padfield iterated that while all visible light is potentially damaging to artifacts, it is necessary for viewing them. To strike a balance between preservation and aesthetics when displaying art, examining various aspects of light sources will help to achieve both. Brian Kraft, Head of Registration, discussed the path the Minneapolis Institute of Art s (MIA) took towards installing LED lighting in "LED Lighting at the MIA: Process, Experience, and Results." The journey began in 2008 as a result of the need to reduce costs and the creation of a Green Team at the museum. During testing they found that people preferred 2700 and 3000 K LEDs best and so the museum uses a blend of the two LEDs. Interestingly, in the “blind” test visitors did not prefer the look of traditional halogen lighting. MIA negotiated a reduced price on their LED lights, which decreased the payback period. During LED installation, the MIA kept the public informed and put out a donation box to “buy a light bulb,” and received positive feedback on both initiatives. After installing the LED lights, the staff and visitors noticed in the galleries the blues and greens were more vibrant, there was more depth to paintings, and frames visually popped more. However, when lit with LEDs, the gray gallery walls color shifted to purple and old conservation repairs become more visible. As a result, LEDs are now being used in the conservation labs that serve the MIA so that the lab lighting mimics the exhibition environment. From the use of LEDs, the MIA has saved about $3,135 per month and reduced watts used by 205,190 per month. Brian Kraft suggested that museums get a warranty for the LED lights and date the back of the lights during installation to track the warranty date. Steve Weintraub of Art Preservation Services, asked the question “Are LEDs Ready for Prime Time in Museums?” and concluded that there is no single answer that applies to all museums. He addressed that some museums are switching to LEDs due to green initiatives, a need for cost savings, or new construction and renovation projects. Others are pursuing LEDs by choice or a desire to reduce energy costs, reduce maintenance, and improve quality of light. He recommends referencing the Department of Energy’s Solid State Lighting web resources to help guide calculations for cost and benefit of switching to LEDs (http://www1.eere.energy.gov/buildings/ssl/index.html). When choosing to purchase LEDs, he recommends that museums test them first, consider whether it would be better to buy now or wait, and aim for a realistic two-year payback period. Improvements are always being made in LED technology and prices are going down: what you buy today will likely be replaced by a better, less expensive bulb tomorrow. Richard Kershner, Director of Conservation and Preservation, talked about the history of LED use at the Shelburne Museum. They began using LEDs inside cases in 2005 to light their dollhouses. In 2010 they began a historic interior retrofit switch to LEDs and are currently doing tests to determine whether to buy new dedicated LED luminaires or retrofit their existing products. Richard emphasized the importance of testing LED lights, negotiating a good warranty, and using multiple LED manufacturers. Gordon Anson, Chief Lighting Designer at The National Gallery of Art, showed a series of slides taken from exhibitions over the past 30 years. The images were of the same gallery space taken from the same position and demonstrated the change in lighting the gallery over the years as they introduced LEDs. The panel discussions fielded practical questions about using LED lights and considered the use of LEDs in situations other than galleries. The panels said that more work needed to be done on why LEDs flash when they fail. Dimming is complicated for LED lights and the most important factor is to ensure that the LED lights and dimmer are compatible with each other and then to test it in your own gallery. The panels concluded that the principles applied to selecting LEDs for gallery spaces also applied to behind the scenes areas and libraries. LEDs with more light in the blue range enhance contrast even at low lighting, which may be helpful in library settings. The panels also discussed whether museums should try to mimic the lighting in which the artwork was originally created. Scott Rosenfeld set up a gallery space as a LED lighting lab. The displays included a comparison of different CRI values, chromaticity variance in halogen lamps, color variance in LED lamps, effect of intensity on color appearance, comparison of color rendering under halogen and LED lamps, and LED beam distribution. To conclude, this conference provided the most current thinking on the state of LED lighting for collections exhibition use. It is critical that we understand the complexity, benefits, and risks of the entire exhibition environment, and the assembled presenters clarified what our questions should be as we move forward using new lighting technology. Here's to continuing the process of sharing: investigation, the decision making process, and solutions.