Some notes on Maghribi script @ ^*I. adn den Boogert

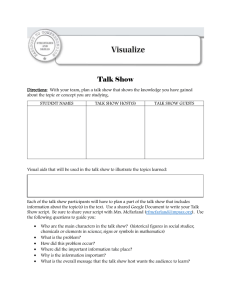

advertisement

Some notes on Maghribi script

@ ^*I. adndenBoogert

In writing the presentstudy, I wanted it to servea Apart from this general characteristic,the distinctive

doublepurpose.

featuresof Maghribi script are the following:

In the first place,it is intendedas a concisemanual l. the final aliJ is drawn from top to bottom;

for the reading of Maghribi manuscriptmaterial, 2. the stems of alif, lam, lam-alif and ta'lza' have

which often posesproblems,evenfor nativespeakers

club-like extensionsto the left of their top point;

of Arabic.The cursivestyleof Maghribiscriptas well 3. the ioop of ;adlQad is identical with that of n'l

'tooth';

as the calligraphicstylecontainmany letterformsand

za', i.e. it has no

ligatureswith which the averagereaderof Arabic is 4. the stem of la'lZA'is drawn diagonally;

unfamiliar.

5. qa/ andfA'have unconventionaldiacritical points;

Secondly,this article, and especiallythe list of 6. final and separate dalldhAl are very similar to

letterformswhich constitutesthe largestpart of it, is

initial and medial kaf, especiallyin the earlier mss;

meant as a possiblestarting-pointof further, more

more differentiated forms developed later;

thorough researchinto the paleographyof Maghribi

These are the features that distinguish Maghribi

script. Attention is focusedon the individual letter- script from the Mashriqi scripts (.naskhc.s.).

forms which make up the script.

Houdas (p. 95) states that 'la différenceque I'on

The manuscriptmaterial on which the notes on constate entre les formes du maghrébin et celles du

diacriticpointsand vocalisationand the list of letter- neskhy n'est pas très profonde'. The differencesdeforms are basedhas beenlimited to specimens

pro- scribed above however, though they are indeed not

duceddurins the l9th and 20th centuries.

very profound, give valuable indications about the

THE ORIGIN OF MAGHRIBI SCRIPT

The origin of Maghribi script has been investigated

by O. Houdasl. In his essayhe examinesthe historical

circumstancesunder which the introduction of the

Arabic script in the Maghrib took place, and he

compares a few 9th-century Maghribi manuscripts

written on vellum. He comes to the conclusion that

Maghribi script is a direct descendantof 'Kufic'. He

even goes so far as to call Maghribi script 'une légère

transformation du coufique' (p. 96).

The term 'Kufic' is somewhat ambiguous. In general. it should be taken to mean the 'formal bookhand

of the 1th - 10th century AD'. Houdas uses 'coufique'in opposition to 'neskhy', which term he usesas

a genericname for the cursive scripts of the Mashriq

(naskh, t huluth, etc.).

That Houdas' conclusionabout the origin of Maghribi script is correct, though perhaps stated a little

imprecisely, becomesclear when one takes a closer

look at the distinctivefeaturesof this script. A generai

characteristicof Maghribi script is what Houdas calls

'la

nature du trait': Maghribi is written with a sharp

pointed pen which produces a line of even thickness,

while in the Mashriq the point of the pen is cut in the

form of a chisel,producing a line of varying thickness.

Manuscriptsof the Middle East4 ( 1989)

origin of the script: it is preciselythese features that

are found in a certain angular formal bookhand

('Kufic') which was usedin the Middle East in the SthlOth centuriesAD. This bookhand is exemplifiedby

Yajda2 plates 4 and 53. In Arabic it is sometimes

referred Í"o as kufi murabba'. The most formal form of

this hand is representedby the Quranic script which is

'Eastern

usually called

Kufic' or 'Qarmatian', see

Lingsa, plates ll-21. This angular bookhand, to which

Maghribi script is apparently closely related, should

be distinguishedfrom a more rounded bookhand (kld

mudawwar) which existed in the same period, and

which was primarily used for copiesof the Quran (see

Vajda, plates 1,2 and 6ab, and Lings plates l-9).

At the time Arabic script was introduced into the

Maghrib (8th/9th century AD), it had already split

into two different styles in the Mashriq: a formal

style used for copies of the Quran, works of law and

jurisprudenceand the like, and a cursivestyle, used in

correspondenceand administration. Both these styles

were developmentsof one original style, the archaic

Arabic script of the 6th and early 7th centuriesAD. In

the 7th and 8th centuries different styles developed for

the various applications of the script. The formal,

calligraphic style ('Kufic') soon became more or less

standardisedand hardly changed during the time it

remainedin use.The cursivestyle on the contrary was

not standardiseduntil the 10th centurv AD. when.

g 19,2312HA Leiden.Netherlands,1989

Q Ter Lugt Press,Donkerstee

ISSN 0920-0401

a 1

i l

N . V A N D E N B O O G E R T .N O T E SO N M A G H R ] B I S C R I P T

under the pressureof the exigenciesof more speedier

ways of writing, severalcursive styles had developed,

all quite different from the formal style. It was Ibn

Muqla (d. 940 AD) who elevatedthe cursive stylesto

the calligraphic level by devising a system which he

called al-khatt al-mansub.With this systemthe letterforms of the cursivestylescould be standardised.This

made their use for non-casual applications such as

Qurans and lawbooks possible, and the old formal

style or Kufic soon went out of use(l lth century AD),

exceptfor ornamental applications.

Houdas arguesthat only the old formal style of the

Arabic script ('Kufic'), was introduced into the

Maghrib. From the centresof Islamic learning such as

Kairouan and Fes, the use of the script spread over

the Maghrib, and after a time it beganto be applied to

purposesfor which in the Mashriq the cursive scripts

were used. Around the beginning of the llth century

AD the formal bookhand as a whole had changedinto

a more cursiveform, which could be written faster and

easierthan the old form and which has remained in

useuntil the present.

DIFFERENT STYLES

Houdas also tries to describethe characteristicsof

the various stylesof Maghribi script. He first makes a

difference between two levels: the calligraphic level

('l'écriture soigné')and the non-calligraphicor cursive

level. He then divides the calligraphicscript into three

styles.Each of these styles had as its place of origin

one of the cultural and intellectual centres of the

Maghrib. These are: Qayrawànr (from Kairouan),

Fàsi (from Fès) and Andalusr (from Cordoba).

Houdas also distinguishesa fourth style, Sldáni,

which originated in the Timbuktu area, and is nowadays usedin the entire sub-Saharanzonelrom Senegal

to northern Nigeria. This style is treated by Houdas as

cognatewith the other three stylesof Maghribi script.

But judging by the very distinct character of Sfidánr,

which is easily recognisable,this style probably developedparallel to, but independentfrom the script of

the Maghrib, and should be treated as cognate with

Maghribi script as a wholes. Sldáni is therefore not

dealt with in the presentarricle.

For each of these styles Houdas mentions a few

characteristics(pp. 108-112),about which he himself

says, however: 'Toutes ces indications sont un peu

vagues,mais il est impossiblede leur donner une plus

grande précision.' Houdas gives various reasons for

this difficulty in establishingthe features of each of

thesestylesin a more definite way.

Firstly, a standardisedform or a calligraphic ideal,

such as existedfor the stylesused in the Mashriq, has

never come into being in the Maghrib. According to

Houdas, this is a result of the aversion against regularity and symmetry prevalent among the artisans of

the Maghrib.

Secondly,the scribesof the Maghrib had the habit

of imitating the specimensthey were copying, which

could have been written in another region or country;

this is, of course,to a large extent a result of the lack

of a calligraphicstandard.

Thirdly, the massiveremigration of Muslims from

Spain definitely muddled up the different styles, as far

as they existed.

Finally, the number of dated manuscriptsfrom the

Maghrib is relatively small.

After describing the four calligraphic styles which

he distinguishes,and naming each of them after its

possibleplace of origin, Houdas says (p. 110): ,...

mais il faut bien remarquer,que le nom de ces écritures n'implique nullement la nécessitéqu'ellesaient été

tracéesdans I'une ou I'autre des deux villes auxquelles

ellesdoivent leurs appellations'.

Houdas also tries to give a classification of the

cursive Maghribi scripts. These he divides into four

g e o g r a p h i c atly p e s : ' t u n i s i e n n e ' , ' a l g é r i e n n e ' , ' m a r o caine' and 'soudanienne'.Bearing in mind the problems already encountered in trying to classify the

calligraphicalstyles,thesenamescould at best be used

to roughly indicate the area where a particular ms.

was produced; they do not tell us anything about the

featuresof its script.

The possibilitiesof making a more definitie classification of the different styles of Maghribi script seem

to be small.

The best prospectsare perhaps offered by a close

examination of the script used in legal documents,

especiallythe more luxurious ones. These documents

usually bear a place and date, and it is improbable

that they have been copied from specimensfrom an

entirely different region. From the list of letter forms

(see below) it becomes clear that Maghribi script

containsa wealth of peculiar letter forms and ligatures

(see for instance the lam-alif and the atif + tam-alif

ligatures).If these forms could be dated, they might

give a clue as to the place and date of origin of

undated MSS.

THULUTH MAGHRIBI

In many Maghribi MSS a script different from

Maghribi script proper is used for the writing of titles,

chapter headings and the like. This is often done in

red, green or blue ink. This script is characterisedby

the very loose form of its letters,which makes it easily

distinguishablefrom Maghribi proper.

Also, severalof its individual letter forms are different,e.g.:

1. the alíf and the lam have a top-serif to the right

instead of to the left:

( tl A

t

l |

I tï

(

v /

) ) ) )

J./.

M A N U S C R I P T SO F T H E M I D D L E E A S T4 í I 9 8 9 )

2. the final alif is drawn from bottom to top:

A cluster of three points written above the line or a

cluster of two or three points written under the line

may be replaced by a flourish similar to an inverted

comma:

c

gf*o

3. the ta'lza' has a vertical stem instead of a diagonal one:

4. the kaJ'hasa flag-like top stroke, and usually a serif

at the top of the stem:

@

@\ \

\\

\

1 1

\

(í.J É rttatirtt

-;;

"/,,r-G,

|V C*) bavna

2. Shadda

Two systemsare in usefor the notation of shadd.

The conventional

systemwasonly found to be used in

the QuranicMSS examined:

6 shadda+ farha

ww shaddaI kasra

5. unconnecÍed dal and initial and final stn and ba'

(etc.) also have serifs:

ooN

shahr

3

N

w snadd1 *

G2è

dumma

A second system, of which the place and date of

origin still remain to be established.was found in the

6. the lam-alif has the followins form. with two r.rn_

'"tother MSS. In this system,a V-shapedsign is used.

serifsto the right:

This sign is written in different positions with a

varying orientation to represent both shadd as the

foilowing vowel:

U'

li,tt cm-nas

7. the pointing of the ./a' and the qaf is often done in

the conventionalway in this script (seefor instance

(.' SJ t ad-dtn

Lings plate 712: ,surat al-qari'a, and plate I l3:

sadaqa llahu I-'aVtm).

This script is sometimescalled maghribí mujawhar

For extra clarity a vowel sign may be added,

or, more commonly, íhuluth maghribt.It is the Maghalthough

this is not strictly necessary:

ribi interpretation of thuluth, one of the six canonical

/

sty\es(al-aqlam as-sitta) used in the Mashriq, whence

v u / v

it was imported into the Maghrib, probably around

, _shadda + fatha

the 13th centuryAD or later.

':

shuctcta

+ damma

:L

Thuluth maghrihï was also often used for inscriptions. e.s. in the Alhambra.

jlta,-nur

TrTshaddalkasra

DIACRITICAL POINTS AND VOCALISATION

3. Wasla

The conventionalwasla(") does not occur in the

examinedMaghribi texts.Instead,to indicaten,asla

The diacriticalpoints of two connectedlettersare smalldot can be writtenover the alif6, e.g.:

v , '

often written togetherin a cluster.This can only be

,(l.l I q.íD hu*attah

done, however,when one of theseletters has two

diacriticalpointsand the other only one,i.e. no clusters

In fully vocalisedtexts, the final vowel sign of the

of more than threepointsare formed:

preceding word is written a second time with the atif

1. Diacriticalpoints

Corl ''nn

*"

QP boY'o

1t,

al-wasl. A repeatedfatha is then placed between the

dot and the alif, and a repeatedkasra is written below

lhe ali/. When the final vowel sign is a damma, a small

horizontal line similar to fatha and kasra is drawn

through the middle of the alif :

N . V A N D E N B O O G E R T .N O T E SO N M A G H R I B I S C R I P T

i :

ilI

1

A

(, ^j.=,-Én

\/'

Y a l

When lhe alif is contained in Ihe lam-alif ligature,

the hamza is placed inside the lam-aliJ or before it,

e.g.:

sadaoa llcjh

o

J.^^) bisni ltatt

\-

J\D,

éót

r Y r i: . ï

A JT ^,ÓJ->

.:-

al- att

OlJ.l aL'an

hnh:nhullah

6. Long a

When alif al-v,asl stands at the beginning of a verse

or sentence,its usual prothetic v o w e li s w r i t t e nw i t h i t :

A long á, which in Modern StandardArabic (MSA)

is regularly spelleddefectivelyor, in vocalisedtexts,is

indicated by a 'dagger ali/', is frequently spelledplene

in Maghribi texts,e.g.:

o .

-o-11

.4 \-/..

sJ I al-vawm

L

lJ tó hadha

4. Hamza

d s to hadhihr

Hamza is frequently omitted, even in partially vocalised texts. When written at all. it takes one of the

following forms:

9 t

J=JIsaturiruo

àDl',,un

s

9 e

The form e

of9:

9

33

is possiblya graphicdevelopment

9? e

When the chair of the hamza is an initial or medial

.va', the hamzais placed below the line. The diacritical

points of the ya' are often written together with the

hamza:

'á7*b

aa tra

The long a in allah, however,is always spelled

defectively.

In vocalised texts the defectivelyspelled long a i s

representedby fatha followed by a small separatealí'

which is placedabove the line, e.g.;

't

(-*h-I=J l,l-ktah

When precededby a lam. this separate alif is drawn

diagonally through the lam, e . g . :

vra-lakin

2r.)*'

sa'ír

The long a in allah is representedby .fatha only:

= ï'i

al-jaza'ir

uàtrÈl

5. Madda

c^JJ

I allalt

7. Vowel signs

The vowel signsJatha, kasra and dammaand the

The madda (*)

is used to mark a long vowel tany;ïnare writtenin a conventional

way:

which is followed by hamz or by a doubled consonant,

_ Q

e.g.:

"' vT

ó S L madda

rí

l -

2u

l-an

s l+ ia'o

e

Ein

(2 han.

ó

n partially vocalised texts the madda may be written

while the harnzais omitted:

T)\,re

ma

The combination of hamz plus long a, which in

conventional Arabic spelling is representedby alíf

with madda 1T;, is written in Maghribi script with

alif precededby hamza, e.g.'.

2un

8. Adaptedletters

The phonemeg that occursin the spokenArabic of

the Maghrib is written either with jïm or qaf. or with

oneof the adaptedletters

..*.,

5, U ,

èt,

gish Qayshl

t2i.i;?

i.

Wle'a,,r,

blt{l

aLqu,'a,

gum(quv'm)

(9

, i

(name)

Gannun

OJjJ

5+

M A N U S C R I P T SO F T H E M I D D L E E A S T4 í I 9 8 9 )

The sound v that occurs in French loanwords is

written either wthfa' or with the adaptedletter (,

1.

e.g.:

,*Alavrit

9. Numbers

European numeralshave beenin common usein the

Maghrib alongside conventional Arabic numerals,

sinceat leastthe beginningof the l8th century. In fact,

they came to be preferredto their Arabic counterparts

during the l9th centurye.They are written in a characteristicstyle:

6. a small dot indicates the point where the letter

forms are connected to the preceding and/or following letter form;

7. cursive forms are given only when there is a considerable difference between them and the more

calligraphicforms.

o"l-f tr

ALIF

1 2 3 15 6 7 t 5 e 0

The form of the numeral8 is typical.

Letter no. 17 in Houdas (1891)containsa date

ghubartnumerals:

writtenin the so-called

Ilz

tr

tr

tr

tr

tr @

(l)

sep.

ío ,tuo

_l-

In a note on this letter Houdas says that these

ghubarïnumeralsare much used in easternAlgeria

and in Morocco.In the manuscriptmaterialexamined

for this article,however,they occuronly once.

-

'

t

-l-

'

'-t-'

10.Paragraphmarkers

The sign :? ir commonlyusedto mark the end of

a paragraph.

To mark the end of a paragraphor of a wholetext,

may be used.

the abbreviationlP f.,

(j&lintaha

E@

M

tr

tr

LIST OF LETTER FORMS

This list, though not exhaustive,gives a good clue

to the variety of letter forms one encounters in the

average Maghribi manuscript. It is arranged as follows:

1. for each letter all variants are given which were

found for its initial form (abbreviated in.), its

medial form (med), its final form ffin.) and its

Occursfrequently

in:

separateor unconnectedform (sep.):

2. the basic forms are followed by ligatures (if presayyidund

6-sent),which are arranged alphabeticallyand which

bi-íarkh(see

note5)

can be found under the first of their two compo. 1í9Y.

nent parts;

3. variants of a certain letter form are arranged in a

horizontal line if they strongly resemble one another, or if one is a graphicaldevelopmentfrom the aÁ'1rÁ'1ruÁ', N7lv (initialand medialTt.

YÁ'

other:

tial and medial)

4. variants of letter forms between which there is a

considerabledifference,or which have each devel( 2,3)

oped into widely different new forms, are arranged

in a vertical line;

5. letter forms marked with a small letter c were

found in cursive texts onlv;

(r)

V

(g.*", _r,a

f"

trlolo'

lini-

N , V A N D E N B O O G E R TN

, O T E SO N M A G H R I B Í S C R I P T

fin.

tr

l

/

tr

tr

t-,-l

tr

tr

-b-j

-b-d

-b-m

b-j

(2)

'

e

bi-rartkh

tW

The ra'is sometimesconnectedthrough:

'Ágt

hi-rarrkh

Thisligature

i, urrÍuri u, u rrr,t., abbeviation

of:

sep.

l

35

. 1 1

f.ercetera.:

á

\-.

. ) 'ila'akhirihí

l

/

t-

(6)

This form is extremelyambiguous.It was found to

represent

the followinglettersand ligatures:

bA'@rc.)or sïnfshïn + jtm (etc.):

(6)

(s)

bi-taríkh

^lr:J

'

. /

In the basmala, the initial ba' often has the same

height as the lam:

l\-,'iJl

r i

as-shavktt

st

I . lJ bismi

d.IJ

,ah

=_ :r_

t

bbi-farh

-

ZlÀl

L

'bridge'

The

form of initial ba' (eLc.),which in the bà'(etc)+ datldhat:

(3 )

an-nusakh

scriptsof the Mashriqsuchas naskhandruq'ais used

A

when it is followed by jrmlhA'lkhA',mïm or ha'

Z'..V bi-.t'ud

(medial),occursin Maghribi script only in the fol^

lowingcombinations:

<,Yjayyid

ba (etc.)I mtm,e.g.:

r

ba'(etc) or stnfshtn * mím:

" l

I-€. ui-na

1t"-)l

khàtuttt

*

aLmo,sim

f

#tlar-,attt,,t

ba' (etc.) + nun (final),e.g.:

I

(-nl

ibn (seealsonote26)

aat'.

ba' (eÍc.)-l ra'fzay,e.g.:

#twa-ba'd

uf (f barta

bi-hadha

But in all thesecasesthe 'normal'form is alsoused.

and seemsindeedto be preferred:

C

{\^-,

L- khatam

4*l(gat-'ahart

dal + ya':

7g1iun

(4)

SIdI

gt I barrd

The 'bridge' form of medial ba' (etc.\ and of initial

and medial sínlshtncan be used when it is followed

by jím (etc.), mtm, ha' (medial) or ya'(final). Seealso

ligaturesunder (6).

(5)

Occurs frequently in:

4lathclhí

kaf + mrm(withor withouttop stroke):

/\tJ-c,

.ara).kunt

1_

#LL-p,abukum

JO

M A N U S C R I P T SO F T H E M I D D L E E A S T4 í I 9 8 9 )

ltl ,u,

lam * jtm (etc.):

lam + mím'.

*l

,to*

nu 1nÀ'1

xnÁ'

in

tr

tr tr

tr tr

tr

tr

med.

fin.

.'EW

{i)nstin

(7)

The dalldhal may easily be confused with kaJ,

sincetheir formsare sometimes

verysimilar,especially

in cursivetexts.Completehomography,however,is

usuallyavoided,e.g.:

9J5ana*o

(8)

To avoid confusion with final ra'f zày, a small dal

is sometimesadded to f,nal dalidhat:

(e)

Occursfrequentlyin:.

Í f,l.ÍD hadha

v

(6)

sep.

DALIDHAL

o'[-al

tr l.cl,u,,

trtr

(')

IJ:l

,.pF.l

tr

tr

h-qatt

:P

(10)

Occursfrequently

in :

')latbdhr

J l , rr

oL

nÁ'12Áv

o"17

Ld

,.p

[-/ I rrrr

'hF]w

t--_-l

tÍ_l

,.NEI

V

.0.[Glter

d'F:l

dvEtriT"o'

trtrÁ

,,Fltr

(12)

EAa

,r[?tr

trÁ

N . V A N D E N B O O G E R T .N O T E SO N M A G H R I B I S C R I P T

trtr@

E

tr E

(ll)

Unconnected

ra' may be connectedto the following

letterin:

-AW

bi-tartkh(seealso note 5)

^re

sep

rahma

(12)

Thisligaturealso represents-rznin:

i , a ,

P

asnrtn

-s-r

\-

sfuisH1ï

,'Fllro,

e

med.

fin.

sep.

(l 3 )

tr tr

tr tr

tr tr

(13)

Occursonly in:

v

v

''le

sÁo1oÁo

(14)

tr

-'dFl

tr EI

tr

n'Fl

(14)

(15)

G)

) l

q-v

tr tr

tr a

(.16)

( t7)

í14)

The initiai and medialforms of sad anddàdhaveno

'tooth',

as in the Mashriqiscripts.

(l 5 )

The vertically elongatedform of medial gadl/act

may be usedwhenit is followedbyjtm (etc.)or rmm,

yandiju

(l6)

Occursfrequently

in:

'7.

b 9>'

The diacritl"ut po*

insidethe loop:

l-tudr't

of the dad issometimesplaced

"r

er,;.;.a.;

shaykh

sallama

(17)

This ligatureoccursfrequentlyin:

,-tAU

TA'tZA'(18)

'"

[,.]

a

tr

",.0i;l

a

tr

I ut-qadr

38

M A N U S C R I P T SO F T H E M I D D L E E A S T4 í I 9 8 9 )

trtrtr[El.n,

tr

@

tr tr

tr @

tr

g

tr trK

fin.

(20)

The height of the loop of the initial

equal to that of the lam.

FÁ'Qt)

t

tr

tr

tr

fin.

QÁFQt)

in.

med

While in the Mashriqi scripts the stem of the ta'l

za' is only added after the loop and the lettersdirectly

connectedto it have been written, in Maghribi script

the stem is usually written first. This explainsthe wild

forms into which lhe ta'lza'have developed.

fin.

t-l

fin.

sep.

(22)

tr

tr

tr

tr

g

sep.

AYNIGHAYN

l*'l

(22)

t-c-l

t ' t

sep.

(le)

med.

l

med.

(l 8 )

The diacritical point of the ;a' is usually piaced to

the left of the stem.

(20)

may be

trt

in

sep.

tr

tr tr

tr tr

tr

tr

tr

'ayn

(22)

(22)

er\

The bestknown characteristic

of Maghribi scriptis

the differentpointingof fà' andqAf:fa'has one point

underthe line and qa/ has one point abovethe line.

(22)

The diacriticalpoints of final and unconnected

fa',

qal and nun are regularly omitted. While diacritical

points are not strictlynecessary

here,sincein theory

these letters are all written differently in final or

position,the differencebetweenthem is

unconnected

oftenhard to see,evenin calligraphicspecimens.

KÀF

(23)

N , V A N D E N B O O G E R TN

. O T E SO N M A G H R I B I S C R I P T

39

tr

'i-r [f o'

[I

tr

H

tr

tr

tr

tr

EE

t-l tr

tr

tr

tr tr

u

tr tr trtrJ"cl,s,E

med.

LAM

(23)

l-'l

med.

(27)

(24)

fin.

(23)

fin.

l-'l

sep.

w

í 75 \

sep.

(23)

(6)

(.26)

The short, curved form of initiai lam is usedwhen

is followed by jtnlhA'lkha' or mtnt, e.g.:

8 L?l at-madt

C)l

' v at-hizh

trtr

trtr

(27)

A shortenedform of medial lam is often used in

xil ,,uo

(23)

Thetop strokeof thekaf is sometimes

doubled:

It

,5J5 ritka

;J j l(lt

-r-j

-l-m

at-karthiba

MIM

in.

med.

(24)

Only used when followed by flnal mtm, e.g.'.

hukm

Seealso (6) above.

fin.

(2s)

Occursfrequentlyin:

(6)

/rt:,é'Jltanunm

The combination of initial lam and final kàf sometimes has a dot added to it in order to distinguishit

from the ligature of alif plus lam-atiJ'

, e.g.:

U s cthatika

tr

tr

tr

tr

tr

tr trtr

tr

sep.

-m-d

(28)

40

M A N U S C R I P T SO F T T I EM I D D L E E A S T4 í ] 9 8 9 )

(28)

Occursfrequently

in:

I--;---ltt_-l

tt

L1!L:j

Muhammad

tr tr

L9-]

tr

'Ahmad

tir\l

r--l

"31at-hamct

,Vt/t/ (initial and medial form: seeBÁ')

V"n'

"oJ-ulU

(29],

Occursonly in a smallnumberof very frequent

words and in the word-endins -tn:

'an

ol

(,/

u1l

u/€F:l

HA'

tn.

med.

min

E_l

-.----l

(30)

Occursonly in the combinations

hA' + alí'(seenote

l) and ha' + mïm(medial),e.g.:

1

14 161(

alma rn

r r

| ul-huntàttt

( 31 )

The final ha' is sometimes

writtenwith a disconnectedfinal stroke,especiallyin calligraphictexts (see

for instanceLings, plates l12 and ll3). In attah this

a l s oo c c u r si n m o r e c u r s i v et e x t s .e . s . :

t t

ihn

tr E

tr tr

tr

tr tr

tr tr trtr

tr

@

É.1trtr

//\I)

I attah

(.32)

The unconnected hà' is always drawn clockwise.

which explainsthe way in which it can be connectedto

a precedingletter (e.g. dal or ru').

WÁW

tr

tr

tr tr

E i-.r-i

tr E

E tr

tr tr a

trtrJ[-{r", tr tr l4)

(30)

fin.

t--t.-t

()) \

frn.

(32)

sep.

fin.

sep.

íll)

Ir-_-l

íll'l

-w-h

w-h

-w-y

w-y

lz-_-l

N . V A N D E N B O O G E R T .N O T E SO N M A G H R I B I S C R I P T

4l

E tr

EE

(33)

Frequently used for w,àtt'* aliJ'al-v,iqo1'íl,

e.g.:

ll

tlfrt'ditt'tl

yÁ' (nitial and medial forms: seeBÀ) (34)

fin.

tr

tr

tr

sep

tr

tr tr tr w

tr E gf_l |4r_l

tr

tr

E

gE

tr

Ic

(3s)

l---t

E]

E

sep.

-l-'-m

tr

tr

-l-'-h

E

E

---l

t-ë---r

(36)

(37)

( 36)

Occurs1 n :

(34)

The forms of final and unconnected1a'which are

marked with an asteriskmay represent-r.a'as well as

ra'preceded

b y i n i t i a lo r m e d i a lb à ' l e t c . ) e

. .g.:

èl ''m

ël'otrotr

Ljanr

)Nl

L,lÀ>-

vra-salant

(371

O c c u r si n :

S*,

fugas-sutah

0kl"'lo,,uru

at-rttaní

kharorara

G liJ | ,tr-ttranr

(35)

Theshortforrnoccursfrequently

in

2Íï

LÁM-ALI F

fin.

tr trE

g

LIST OF SOURCES

The notes on diacritical points and vocalisationsignsand

the list of letter forms are primarily basedon the annotated

anthologiesof manuscript material from the Maghrib that

were publishedmainly at the end of the last century, and on

four collectionsof miscellaneousmanuscript texts from the

library of Leiden University. The data yielded by these

sourceswere then compared with ten 19th and 20th-century

manuscripts from the Leiden collection, with a few lithographed Fes editions and with three recenrly published

lacsimileeditions of the Quran.

/ 1

+/

M A N U S C R I P T SO F T H E M I D D L E E A S T4 ( I 9 E 9 )

l. Anthologies

Belkassemben Sedira, Manuel épistolaire de langue urahe'

Alger 1893. Contains 76 letters and documenísin Jacsíntile, n'rost of them from Algeria, w'ith noíes, vocabularr

and transcription in standurdisedÁrahic suipt'

Belkassem ben Sedira. Cours gradué de lettres uraber

manttst'rites.Alger 1893. Contains 319 letíers and documents in facsimile, m(tinlv-.from the Maghríb, but also

some.fi'omSyria and EgtPt'

Houdas, O. & G. Delphin, Ret'ueílde lettresarabesmanus'

crítes,Alger 1891' . Coníainsll0 lettersand documentsin

and transcription in stqn.fac'sintile,riÍlt notes, vocabular.ro.f'the

clarclisetlArabic script

first 2l letter'sand parts of

the rentaíning letters.

'Algerisch-tunesische

Briefe in Faksimile und

Rescher,O.,

in'. Mítteilungen 'les

Anmerkungen',

Transciption mit

Berlin, XX (1917)'

:u

Sprachen

Seminars.fiirorientalisc'he

in

Contains 37 letters facsimile.

Paris 1949' Contains

Watin, L.. Recueilde tertes muroc'ains,

prohuhlr

all v'rítten especiall-v

in

ll2 specimens facsímile,

notes and vocabuY'ith

scribe,

sante

the

b;'

for rhis hook

pet'ulíarities o.f

the

on

notes

gbes

a

Watitt

also

lert'.

fëv'

scriPt.

Maghribi

mi'scellanea(íron thc lihrary o.f

2. Collectionso.f n'tanu'scripr

Leiden)',

of

Llniyersitt'

the

Or. 14022. Collection of documents, 19th120thc' (Witkam. CataloguePP.3 l-34)

Or. 14066:Collection of letters,short texts and fragments,

1 9 t h i 2 0 t hc . ( W i t k a m . C a r a l o g u ep p . 1 3 6 - 1 4 0 )

Or. 14048:Collection of severalreligious and magical texts

in numerous Maghribi hands, 19th c' (Witkam. Catalogue pp.72-89)

O r . 1 4 0 6 1 :C o l l e c t i o no f m y s t i c a la n d r e l i g i o u st e x t s ,c o p y

d a t e d 1 2 9 9 ' 1 8 8 2( W i t k a m . C a t a l o g u ep' p ' 1 2 3 - 1 3 0 )

3. Manuscripts (.from the lihrary oí' the Univer'sitv of Leidetl):

Or. 14169:Anon., Majmu'at nav'hat. l9th-centurycopy

(Witkam, Catalogue,PP.274-278)

'ala

tarttb

Or. 141185:Muhammad b. Abr Sitta, Hashit'a

(Wit127911862

dated

musnad ar-Rabt' b. Habrb, copy

-29

pP.

|

5)

29

kam, Cat al ogue,

4. Fèseditions:

These lithographed books which were published in the

second half of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th

century in Fès show a relatively homogeneousscipt. Some

information on theseeditions is given by P.Sj. van Koningsveld in Brill Catalogueno.5l0, Islamic Collections(Leiden

1979),and recentlyby Fawzi'Abd altazzáq,Al-mathu'at alhajariyt'a .fi t-Maghrih. Fihris mu'a muqaddima ta'rrkhiyl'a

(Rabat 1989). For the composition of the list of letter

forms. use was made of the reproductionsin this catalogue

(mainly of colophons),and of the following editions:

Bábá at-Tinbukti. t{41l al-ibtihaj. Fás l3l 7/ 1900

Ibn al-Qádr,Jadhwut al-íqtibas,Fás 1309/1891

al-Kattánr. Saln'aÍal-'anf'as,Fás I 3 16/ I 898

5. Facsimile editions qf the Quran:

(d.

Qur'an, calligraphy by al-haij Zuhayr Básh-maml[k

1305/1885); Mu'assasat Abdalkarïm b. Abdalláh,

TÍnis 1403i1983

Qur'an, calligraphy by as-shartf Abd al-'Iláh al-Manjara

a s - S a ' d i ;D á r a l - K i t á b , a d - D á r a l B a y d á ' 1 4 0 5 / 1 9 8 5

Qur'an, calligraphy anonymous; Dár at-Thaqáfa' ad-Dár

al-Bavdá'1405/1985

NOTES

1 Houdas. O. 'Essai sur l'écriture maghrébine',ir': l'{ouveauxmëlangesorientaux,IIe sérievol' xix, Publicationsde

des Langues Vivantes Orientales (Paris 1886)' A

I'Ecole

Or. 1350-I: First volume of a five volume set of the

of this article into Arabic by Abdalmajrd attranslation

Muqaclclimaby Ibn Khald[n, calligraphic copy dated

in Hawliyyat al-iami'a at-tunisiyya 3 (1966)'

Turkr

appeared

1 2 3 6Ii 8 2 1 ( V o o r h o e v e .H a n d l i s t .p . 1 2 0 )

'Muháwala fï l-khatt al-maghthe title

under

pp.175-214,

1903

dated

Or. 14006: Ibn Abr Zaf. Ravtl al-qirtas. copy

ribi'.

(Witkam. Catalttgue.PP. l0-1 I )

2 G. Vajda, Atbum de palëographiearabe, Paris 1958

t

h

e

o

n

t

e

x

t

s

O r . 1 4 0 0 7 :A b d a r - R a h m á na t - T i l i m s á n i ,t w o

3 The well-known ms' Leiden Or' 298, Gharíb al-hadlth

h i s t o r y o f A l g e r i a , c o p y d a t e d 1 3 0 2 i 1 8 8 5( W i t k a m ,

by Abu'Ubayd al-Qásim b. Sallám, is also written in this

C a t a l o g u eP, P .l 2 - 1 4 )

Or. 14010: Abdalláh b. Mulrammad at-Tr.fánI. miscella- scnpt.

a M. Lings, The Quranic Art of Calligraphy and lllumineous texts. copy dated 1212 1856 (Witkam' Catalogue,

n a t i o n .L o n d o n 1 9 7 6 .

p p . 1 4 .1 5 )

s The relationship between Sldánt and Maghribi script

of

sultan

activities

the

on

Or. 1402l: Anon., two texts

'The Arabic Calligraphy of

A.D.H. Bivar in

Muhammad b. Abdalláh B[ Sayf' copy dated 12691 is discussedby

West Africa'. African LanguageReviewVII (1968)'

I 8 5 2 - 3( W i t k a m . C a t a l o g u ep, p . 3 0 - 3 )1

ó In older Maghribi MSS l'nsl was indicated by a green

Or. 14036: Collection ol poetry of some rulers of the

was indicated by a red or yellow dot. These

Hafsids in Tunisia and their officials,copy dated 1304/ dot. while hamz

coloured dots used for the notation of v'asl and hamz wete

I 887 (Witkam, Catalogue,PP.62-63)

of a vocalisation system invented by Ab[ lO r . 1 4 0 5 0 :A h m a d a l - M u s t a f á b . U t w a y r a l - J a n n a .R i h l a t a remainder

(d. 688 AD), which consistedentirely of

al-munà h'al-minna.19th century copy (Witkam, Cata- Aswad ad-Du'ali

coloured dots. The greendot was later

positioned

variously

logue, pp.90-95)

the same colour as the rest of the

in

dot

by

a

O r . l + O O : : N o n - c a l l i g r a p h i cc o p y o f M u h a m m a d B e l l o , replaced

yellow dot was replaced by the

or

red

the

and

Infaq at-maysÍr. copy dated 1292!1875(Witkam, Cata- script,

(e).

hamza

conventional

l o g u e ,p p . I 3 2 - 13 3 )

N , V A N D E N B O O G E R TN

. O T E SO N M A G H R I B I S C R I P T

7 In Berber

texts written in the Arabic script, this atif

with horizontal line through the middre is often usedfor the

n o t a t i o n o f w o r d - i n i t i a lu . e . s . :

i;,

L) | urd

8 In Berber texts written

in the Arabic script, the Berber

,

phonemes igi and lql are written witl

í O

\-/-

r e s p e c t i v e l ve.. s

- ' J '

- ' È"

o

:, 1 /-

f-PfS-r

27

I ors,,-

+-l

e In two of the three facsimile

copiesof the euran which

were examined,the versesas well as the pagesare numbe_

red with European numerals. In the third copy the verses

have not been numbered,while the pageshave European as

well as Arabic numerals.