Defining Payback for Energy Saving Measures

advertisement

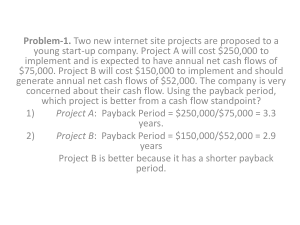

Industry Watch By Rich Walker, American Architectural Manufacturers Association Defining Payback for Energy Saving Measures B e it windmills or windows, energy saving measures are subject to cost-benefit analysis, which is often a point of contention between advocates and skeptics. In the building components sector, the discussion tends to focus on the cost-effectiveness of energy saving measures mandated by codes and/or encouraged by rating programs such as Energy Star. Usually, the defining metric is the payback period—that is, the time it takes for the calculated energy cost savings to amortize the extra cost that energy-saving measures add to a basic fenestration unit. This issue rises anew with the recent reintroduction of the Energy Savings and Building Efficiency Act (H.R. 1273), which is very similar to a like measure that was introduced but failed in the 2014 Congress. It requires that any code or proposal supported by the Department of Energy must have a payback of 10 years or less. A BIT OF HISTORY Where did this 10-year period come from and what basis is there for it? In developing a payback scenario for the Energy Star Version 6.0, the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Energy went through an evolution of thinking in arriving at much the same payback period. Initially, the idea was that the payback period should be the anticipated service life of the product (i.e., 20 or more years). If the savings in utility cost over the service life of the product was more than the incremental cost of the product, it was cost-effective. After this approach was met with a certain amount of skepticism, the DOE figured its own calculations with the issuance of Draft 1 of Energy Star v6.0 that arrived at an average payback period of 13 years. One more 12 | Window&Door | May 2015 iteration for v6.0 produced a payback period of less than 10 years, which is consistent with the legislation. The DOE approach essentially divided the average cost differential between Energy Star-qualified windows and a basic code-compliant window (IECC 2009) by the average incremental energy savings per household in different localities scattered throughout the four Climate Zones. The incre- fied on a localized basis as possible. The National Association of Home Builders weighed in favor of the 10year payback, opining that the bill would ensure that the most practical energy-saving features, such as highefficiency windows, would be included in new homes and result in reduced costs for homeowners. The measure also stipulates that the DOE would serve as a technical ➤➤The Energy Savings and Building Efficiency Act requires that any code supported by the DOE must have a payback of 10 years or less. mental energy savings is based on a whole-house simulation using RESFEN 5 software and utility rates based on 2011 residential data. The average cost differential represents the increase for improving the product to various performance levels (e.g., U and SHGC) to Energy Star v6.0 levels through the use of glass coatings, gas infill, better spacers, etc., and is essentially the difference between an Energy Star 6.0 vs. an Energy Star 5.0 window, which most manufacturers agree was more realistic. CAUSES FOR CONCERN The 10-year payback reference point for the legislation is nevertheless controversial. Part of the difficulty lies in arriving at a payback period applicable nationwide. The DOE analysis indicated that payback ranges from as low as 2.5 years for “average-cost” products and less than one year for “low-cost” products, to as high as 14.5 years for average-cost products and nearly 13 years for low-cost products. High-end products with calculated payback periods of more than 10 years are not prohibited by the proposed rules, of course, but may have to be cost-justi- advisor in the development of energy codes, while prohibiting the agency from showing favoritism for specific technologies, building materials or construction practices. Specifically, the bill would require all energy code change proposals to be made available to the public, including calculations on costs and savings (a cost-impact statement, if you will), allowing public comment and taking into account the concerns of small business. NAHB says this will help code officials make more informed decisions and result in cost-effective code provisions, and that it will curtail the influence of outside groups that seek to advance energy code proposals with little regard to their cost. It remains to be seen whether H.R. 1273 will turn out to be another pass at the brass ring on the merry-goround or a solid step forward in establishing a bona fide reference point for cost-effective energy efficient building components. w Rich Walker is president and CEO of the American Architectural Manufacturers Association, 847/303-5664, rwalker@ aamanet.org.