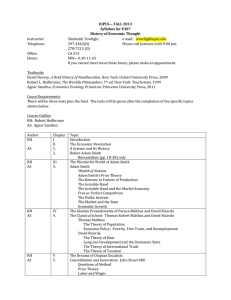

William Stanley Jevons 1835-1882: A Centenary Allocation on his

advertisement