A New Typology of Instructional Methods

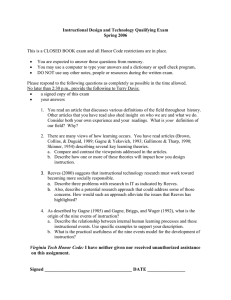

advertisement

18th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning For more resources click here -> http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ A New Typology of Instructional Methods Michael Molenda Associate Professor Indiana University Gagne’s Original Construct In the very last section of his book, Conditions of Learning, Gagne referred to the different types of instructional environments as “modes” of instruction: “Environments for learning consist of the various communication media arranged so as to perform their several functions by interaction with the student. The particular arrangements these media may have in relation to the student are usually called the modes of instruction.” (Gagne, 1965, p. 285) He outlined six different modes of instruction being commonly used (Gagne, pp.285-294): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Tutoring: “interchange between a student and his tutor” Lecture: “oral communication on the part of the teacher” Recitation: “teacher ‘heard’ the students perform” Discussion: “oral communication…between teacher and student…[and] interactions between students” Laboratory: “a stimulus situation that brings the student into contact with actual objects and events” Homework self-instruction: “as [reading] a chapter in a textbook” practice: “examples of previously learned principles” projects: “organize a variety of activities for himself in such a way as to lead to the development of a product” This construct of “modes” was repeated verbatim in the second edition of Conditions of Learning (Gagne, 1970), but it disappeared from all subsequent editions. Molenda’s Adaptation of Gagne It seemed to me that Gagne was onto an important idea here—that you could classify the various instructional arrangements according to the interaction pattern that characterized it. Gagne did not pursue this idea, but I took it one step further, trying to be quite explicit about establishing categories and defining the communication patterns among Teacher, Learner, and Resources (Molenda, 1972): 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Tutorial: two-way interchange between tutor (Teacher) and tutee (Learner) Lecture: one-way information flow from source (Teacher) to many receivers (Learners) Discussion: two-way interchange among Learners Laboratory: Learner acts on raw materials (Resources) Independent study: Learner acts on encoded, instructional materials (Resources) Practice: Learner uses new skill repeatedly (may be guided by Teacher) This seemed to be a handy classification system—small and simple—that was fairly successful in providing “baskets” into which you could place many of the instructional formats that one encounters in everyday teaching (See Table 1). 1 Copyright 2005 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Duplication or redistribution prohibited without written permission of the author(s) and The Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ 18th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning For more resources click here -> http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ Table 1. Modes and Formats Modes tutorial lecture discussion laboratory independent study practice Formats apprenticeship coaching: music lessons mentoring Socratic dialog programmed tutoring branching programmed instruction adaptive computer-assisted instruction oral presentation overhead transparency presentation PowerPoint presentation film presentation radio program television program telelecture seminar T-group buzz group debate panel discussion role-play science experiment social simulation instructional game field work: archeology, anthropology case study project reading textbooks, modules, handouts reading Web pages reading Web “tutorials” programmed instruction linear computer-assisted instruction watching video memorization drill language lab athletic practice drama rehearsal end-of-chapter exercises recitation A theory that accompanies this typology is that what is important is the communication pattern; it provides certain possibilities and imposes certain limits. Once you’ve chose the mode of instruction, the formats are pretty much interchangeable. The particular manifestation of that communication pattern, the format, may bring logistical advantages or disadvantages—textbooks might be more readily available than Web pages for some audiences—but it’s communication pattern that carries the pedagogical power…and limitations. We had learned this with a vengeance in the hundreds of media studies comparing film and video presentations to live lectures. A given message will have essentially the same learning effect whether it is delivered live, over television, or over 3-D holographs. Choices made for logistical considerations—time and money—can be crucial decisions, but they don’t directly affect the pedagogy. Another theory associated with this typology is that certain modes lend themselves to different phases of the learning Copyright 2005 The Boardserve of Regents Universityinterest of Wisconsin process. For example, a laboratory activity might well of tothe stimulate and System. provoke questions about a new Duplication or redistribution prohibited without written permission of the author(s) topic. A lecture would be an efficient to present new information to an audience whose curiosity is aroused. A and way The Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning 2 http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ 18th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning For more resources click here -> http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ discussion can help learners digest new principles and apply them to their daily lives. Practice activities are often assigned as homework in order to develop confidence and speed in application. A Transitional Typology Over the years, as new technologies and new instructional theories entered the stage the typology grew. In 1995, my colleague, Charles Reigeluth, asked permission to put it into print in his book on instructional design theory (Reigeluth, 1999, p. 23). See Table 2. The New Typology Then came Distance Education. When my students and I began to study the pedagogical strategies of Web-based distance courses, we quickly found that the 1999 version of the typology did not provide very adequate “baskets” for holding the various activities that were most common in Web-based courses. This opened our eyes to the realization that “virtual” courses employ lots and lots of learning strategies, but very few teaching strategies. So, in order to capture the teaching and learning methods being employed, the typology must be expanded to include both the methods that the Teacher controls and those that the Learner controls. This leads to the “new typology.” (See Table 3) This typology is intended to portray the somewhat disorderly, asymmetrical picture of reality. The categories are not neatly mutually exclusive; there are overlaps. Some constructs could be portrayed as separate methods or as subsets of other methods. So, this is today’s view. The next step is to test these categories by attempting to apply them to real-world observation of face-to-face and distance education courses. Will these “baskets” prove to be comprehensive, distinguishable from each other, and practical? That’s the test ahead. References Gagne, R.M. (1965) The conditions of learning. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Gagne, R.M. (1970) The conditions of learning, 2nd edition. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Molenda, M. (1972) Instructional design basics. Unpublished lecture notes. Bloomington, IN. Reigeluth, C. R. (1999) Instructional-design theories and models (Vol. II). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. 3 Copyright 2005 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Duplication or redistribution prohibited without written permission of the author(s) and The Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ 18th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning For more resources click here -> http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ Table 2. Typology of Instructional Methods (1999) Method Visualization Strengths Efficient Standardized Structured L Lecture/Presentation L T L L (Realistic Showing) T Demonstration/Modeling Eases comprehension, application L L Tutorial Customized Learner Responsible L T T T T Automatized Mastery Drill & Practice LA LA T Independent/Learner Control LA Flexible implementation Ri L Meaningful, realism, owned, customized to learner L Discussion, Seminar L T L Cooperative Group Learning LA T LA LA Ownership Team-building P LA Artificial rules Games LA LA Realistic Structure Simulations LA LA Context Discovery • Individual • Group T 4 LA LA LA LA T Problem Solving/Lab Rr LA T LA LA LA High Transfer High Motivation Rr High Level Thinking in ill-structured problems P Copyright 2005 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Duplication or redistribution prohibited without written permission of the author(s) and The Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ 18th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning For more resources click here -> http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ Table 3. Molenda’s Typology of Instructional Methods (2002) Teaching Methods (teacher-controlled) Learning Methods (learner-controlled) Presentation (viewing, listening) Active Reading Reflection Demonstration (modeling—teacher, peer) Discussion Tutorial Expression (verbal, action) Construction (non-verbal product) Drill-and-Practice (mental drill, memorization) Discovery/Inquiry Laboratory Simulation Game 5 Copyright 2005 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Duplication or redistribution prohibited without written permission of the author(s) and The Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ 18th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning For more resources click here -> http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/ Biographical Sketch Michael Molenda is an associate professor, Instructional Systems Technology (IST), Indiana University since 1972. Coauthor of Instructional Media and Technologies for Learning, 7th ed. (Prentice-Hall, 2002) and of the chapter on ATrends and Issues in Instructional Technology@ for Educational Media and Technology Yearbook, 1998 through 2002 editions. He teaches in the areas of instructional design, instructional technology foundations, and distance education. Received PhD in Instructional Technology from Syracuse University, 1971 Address: E-mail: URL: Phone: 6 Education 2234, Indiana University, Bloomington IN 47405 molenda@indiana.edu http://www.indiana.edu/~mmweb98/index.html 812.856.8461 Copyright 2005 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Duplication or redistribution prohibited without written permission of the author(s) and The Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/