The case for and against onshore wind energy in the UK

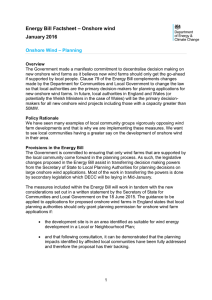

advertisement