Support. Act! Encourage. - Australian Human Rights Commission

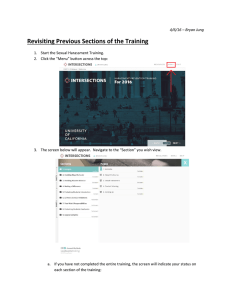

advertisement