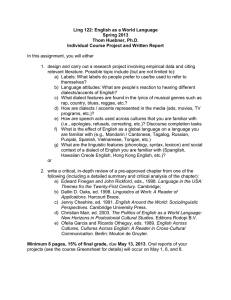

Inviting the Mother Tongue: Beyond “Mistakes,” “Bad

advertisement