The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

“Destroy the scum, and then neuter their families:” the web

forum as a vehicle for community discourse?

Brian Coffey∗ , Stephen Woolworth

University of Washington, Tacoma, Box 358437, 1900 Commerce St., Tacoma, WA 98402-3100, USA

Abstract

On-line media forums have become common vehicles to promote discussion about particular issues

or events. This essay addresses the degree to which the anonymity of such computer-mediated communication affects the level and tone of discourse when sensitive or volatile local issues are the focus

of discussion. Nearly 300 postings to a web forum that was established by a newspaper in response

to a brutal murder that took place in the community are examined. Results show that the forum was

dominated by individuals harshly critical of the assailants, their families, and various civic institutions.

Vitriol, racist denunciations, and calls for severe retribution took precedence over attempts to understand

why the event took place or to express sympathy for the victim. Forums of this nature appear to do little

to promote understanding or encourage positive dialogue. It is recommended that methods designed to

elevate the level of discourse be considered when establishing forums related to local issues that elicit

strong emotion.

© 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The Internet has created countless opportunities for people to communicate, exchange ideas,

voice opinions, and otherwise interact in a manner most would not have envisioned two or

three decades ago. Email, chat rooms, bulletin boards, and virtual communities found in such

outlets as Usenet have altered the manner in which people interact. These new methods of

communication and discourse are often seen as creating a more egalitarian world, at least in

the sense of having one’s voice heard (Walther, 1992). It has been argued, for instance, that

computer-mediated communication offers “an inviting opportunity for democratic dialogue

. . . [that can] . . . contribute to the formation of a spirit of community and civility” (Benson,

∗

Corresponding author. Tel.: +1-253-692-5882; fax: +1-253-692-5612.

E-mail address: bcoffey@u.washington.edu (B. Coffey).

0362-3319/$ – see front matter © 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2003.10.001

2

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

1996, p. 361). It is evident that these increased information flows are viewed as being beneficial

both from an economic and social perspective and that these new means of communication are

often seen as having a positive impact on society.

Others, however, argue that use of cyberspace to communicate with groups of people is

fraught with potential pitfalls, particularly when people espouse strongly held views or discuss

controversial issues. Because electronic communication is remote and often anonymous, “one

never needs to stand face to face with other virtual community members . . . [and] we see

extremes of human behavior and discourse” (Nguyen & Alexander, 1996, p. 117). The result

is that “participants . . . are less inhibited by social niceties and quicker to resort to extreme

language and invective” (Putnam, 2000, p. 176).

That electronic discourse often takes place on a lower plane than face-to-face interaction

is not only related to virtual distance and anonymity. Missing too are social cues that serve

to inhibit people or prompt some change in the intensity or tone of the statements being

made. There is no body language to register discomfort at what is being said, no immediate

verbal response to challenge the viewpoint, and no voice intonation to express disapproval.

In short, many of the things that keep the social self in check are absent. This is a situation that Smith and Kollock (1999, p. 18) liken to “attending a cocktail party and being

able to see only people who are actively speaking, while the room and all the listeners are

invisible.”

But the claim that anonymity may lead to invective is not new, nor is anonymity in computermediated communication always viewed negatively, since it offers individuals the opportunity

to try new forms of expression or interaction without fear of embarrassment (see, for example, Myers, 1987). Moreover, in many instances rules of behavior and conduct do apply to

electronic interaction. This is especially the case in group contexts where people are engaged

in ongoing or long-term communication (Baym, 1998). What is jeopardized in many forums

of computer-mediated communication, though, is civic membership—what Bellah, Madsen,

Sullivan, Swidler, and Tipton (1996, p. xi) describe as “that critical intersection of personal

identity with social identity.” In electronic sites where participants have the choice to remain

anonymous, the temptation to disengage from genuine and authentic interactions with others

is always present and this has profound implications for both the form and function of social

interaction in cyberspace.

Despite these potential shortcomings of Internet discussion, opportunities for interaction

show no signs of abatement. Included among these many outlets for expression are on-line

forums sponsored by various media outlets. These forums are typically found on the web sites

of many newspapers, television stations, and news magazines and invite readers or viewers to

express opinions about current events or issues facing local communities. These sites sometimes

face the same civility issues as other electronic discussion groups. For example, Schultz (2000,

p. 215), in examining the on-line forums of the New York Times notes, “. . . the forum debates

are usually highly political and energetic. While this is desirable in order to revitalize public

discussion, it surely involves the danger of attracting dogmatists and extremists.”

Such forums typically take one of two forms. In some instances they are on-going and

provide for discussion of various topics in the news. Other news forums are more focused in

that they are established only occasionally and are intended to deal with a specific event or

issue that is of particular interest to the community. For example, focused forums may be set up

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

3

to provide a setting for debate on a particular policy issue. Or, such forums may be established

to deal with a particularly dramatic (or traumatic) event that has affected a community. In such

instances the forums are often intended to help people come to terms with what took place,

share ideas about preventing future occurrences, or to voice concerns about the circumstances

that led to the event. In short, forums of this nature are intended to serve the community by

providing an outlet for constructive discourse.

How such forums are used, whether or not they serve their stated purpose, and the extent to

which they benefit the community and/or improve community relations are issues which merit

attention. This essay addresses the matter of focused on-line news forums as potential sites of

productive and beneficial discussion through the examination of one such forum established by

The News Tribune (TNT) of Tacoma, Washington in August 2000. The forum was established to

allow community members to “share” their thoughts about a senseless killing that had recently

occurred in the city.

The forum came about after the death of an individual named Eric Toews, a 30-year-old

resident of Tacoma. On the night of Saturday, August 19th, 2000 Mr. Toews was walking

near the city center when he was approached by a group of youths, one of whom asked for

a cigarette. As Toews paused to grant his request, the group physically assaulted him. Three

days later a brief description of the attack appeared in the crime section of The News Tribune

listing Toews in critical condition. The following Friday, after 6 days in a coma, Eric Toews

died. The announcement of his death was the lead headline in The News Tribune the next day:

“Man dies from beating injuries” (Burns, 2000b, p. A1).

The news story revealed that Toews was the ninth white male who had been robbed and/or

assaulted while walking alone at night in the previous month by individuals described in The

Tribune as a group of “black or Hispanic boys” between the ages of 12 and 15. Tacoma detectives

stated they believed the youths were targeting men walking alone and that they were using a

variety of tactics to approach their victims. The string of offenses was listed in chronological

order on the paper’s front page next to a location map marked by numbered dots indicating

where each crime had taken place. For the first time, Tacoma residents were alerted to a pattern

of escalating street crimes that occurred at night in the same area of the city.

Aside from the brutal nature of the crimes, the information reported in the paper carried

racial and class meanings for city residents, symbolized most notably by who the victims were,

who the suspects were thought to be, and where in the city the crimes were committed. The

majority of the incidents occurred on or near “Division Avenue,” a street aptly named since it

marks the border or “convergence zone” between a low-income, racially-mixed neighborhood

and a predominantly middle to upper-middle class white neighborhood. The string of attacks

was reminiscent of the gang and drug-related violence that had plagued Tacoma for some

time, giving the city a sharply negative public image in the greater Northwest region. However,

Tacoma’s reputation as a crime-ridden metropolis had begun to change in recent years. For

example, in 1993 Tacoma had 35 homicides and 238 reported drive-by shootings. In 2000 the

city had 14 homicides and seven reported drive-by shootings. Thus, this series of attacks had

raised concerns about a resurging wave of violence in the city (Burns, 2001, p. A1).

In the days after Toews’ death, print and electronic media coverage intensified and fliers

bearing Toews’ picture began to appear on store windows, bulletin boards, and telephone poles

throughout the city. Area residents were encouraged to take extra precautions and were warned

4

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

not to walk alone at night. Many expressed anger at the police for not alerting them earlier, while

others questioned whether the crimes might be “racially motivated” and should be considered

“hate crimes.” The police defended their actions by responding that they had not linked the

different cases together until after Toews was attacked, and they assured residents they were

now giving the case their full attention. The crimes, the police maintained, were “crimes of

opportunity,” not racist attacks.

By the night of Monday August 28th, 9 days after the assault on Toews, several suspects were

arrested. Television news reported the arrests on Tuesday, and on Wednesday city residents

awoke to The News Tribune’s headline: “8 arrested in thrill beatings.” The case received

national attention with a news report by at least one of the major television networks. With the

news of the arrests came facts about the suspects. The oldest, a 19-year-old African-American

male, and a 16-year-old Hispanic male were held in the county jail to be charged as adults.

The other suspects included three African Americans (ages 15, 14, and 12), two Caucasians

(ages 15 and 11) and a 12-year-old Hispanic youth. City residents learned that the suspects

had been harassing others in their neighborhood for some time, and, in fact, were stopped and

questioned about the assaults by the police the previous week. Patrol officers even drove some

of the youths home after questioning them so that they would not be in violation of the city

curfew. After the arrests, the statements from the police in both the print and television media

reiterated earlier assertions that these were, indeed, opportunity crimes. As the lead homicide

detective bluntly concluded, these “kids would just get together and decide to go beat someone

up” (Burns, 2000a, pp. A1, A16).

In the court papers released later that day, prosecutors described the attack. When the group

saw Toews walking across the street, the 19-year-old asked the group if they “wanted to get

him.” The 12-year-old approached Toews and asked for a cigarette. When Toews reached into

his pocket, the 19-year-old assaulted him. Toews was then knocked to the ground where the

other youths moved in kicking, hitting, and stomping him. The 11-year-old boy reportedly

beat Toews with a stick. At one point during the assault, Toews was able to get away only to

be knocked down again by the 19-year-old who then proceeded to knee-drop Toews 28 times

in the face, counting each knee drop aloud. The group of young attackers then fled the scene

when they saw a person nearby placing a telephone call.

As the arrests and the details of the case became public on the afternoon of Tuesday, August

29th, The News Tribune announced it was starting an “open forum” on its web site inviting

community members to “share your thoughts” (Reid & Gillie, 2000, p. A1). For the next 3

days, hundreds of people logged on to the site and posted their thoughts, opinions, and feelings

about what had happened. This paper provides an analysis of the forum’s content in order to

obtain some insight into the value of this medium as a means of promoting positive community

discourse and understanding, especially in cases where the topic is one that has considerable

potential to provoke anger, ill-feelings, and social division.

2. Methodology

The News Tribune’s forum site was started late in the day on Tuesday, August 29th and ended

at approximately midnight on Friday, September 1st. Because we were unable to recover what

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

5

we estimate to be the first 30 to 50 messages posted on Tuesday, our data are comprised of all

forum posts from early Wednesday morning through Friday night.

We began our content analysis of the cyber forum by grouping the responses or “posts” by

day—Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, respectively. Each post was reviewed to determine its

primary theme or point of view.

Posts were sorted into six categories as follows.

1. Those that tended to blame or criticize society in general for the crime.

2. Those that criticized or expressed hostility toward the youths and/or called for retributive

justice.

3. Those that criticized or blamed the families of the youths. These posts may also have

included criticism or condemnation of the youths themselves.

4. Those that contained institutional criticism. These included criticism of the media, the

criminal justice system, the police, and/or the department of social services.

5. Posts that expressed sympathy for the victim and/or his family.

6. “Other” posts that did not fit any of the above categories.

In addition, any mention of race in the posts was recorded according to comments that had

explicit racial and/or racist overtones versus those that discouraged or challenged racist posts

or sought to promote racial understanding. In only a few instances was race or racism judged to

be the primary topic of a post. In such cases, the post was listed in the “other” category. Thus,

figures shown for race in the data set are derived from the values listed for the six categories

shown above.

Further, to avoid having any one individual or any group of individuals skew the results

by repeatedly expressing views, we included only one post per person per day. In the case of

multiple posts, only a person’s first post of the day was included in the data. However, we did

examine the content and frequency of multiple posts by repeat users to determine the degree to

which a sense of community developed. Admittedly, limitations exist here in that it is possible

that individuals participating in the forum used different names when sending messages. It

was only on Friday, the final day of the forum, that we were able to obtain the IP addresses of

the forum participants from the site’s webmaster. This information allowed us to discount the

repeated posts of one user who registered under different names.

3. Findings

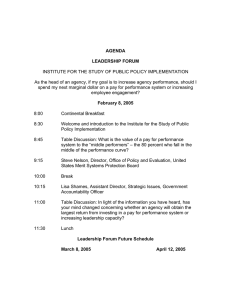

In total, 279 comments were examined. Of these, 60 or 22% were written on the first day

of the forum. This figure increased on the second day when 105 statements (38% of the total)

appeared. The third day saw the largest number of comments with 114 messages accounting

for 41% of the total. The increase in numbers over time is, in all likelihood, a function of the

fact that the newspaper hosting the site noted its existence each day in its published editions and

invited readers to provide input. Thus, the increase in activity is probably due to an increasing

number of readers becoming aware of the forum with each passing day.

As the title of this essay suggests, anger and outrage were commonly expressed in the forum.

In general, writers tended to be critical to one degree or another with nearly 80% of all messages

6

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

Table 1

Forum posts by primary subject

Day 1

Day 2

Day 3

Total

Blame placed on society in general

Blame placed on youth involved

Blame placed on families of youths

Blame placed on various institutions

Sympathy expressed for victim or his family

Other

12% (7)

8% (5)

18% (12)

35% (21)

5% (3)

28% (12)

11% (12)

30% (31)

18% (19)

24% (25)

5% (5)

12% (13)

11% (12)

9% (10)

26% (30)

29% (33)

6% (7)

19% (22)

11% (31)

17% (46)

22% (61)

28% (79)

5% (15)

17% (47)

Negative racial comment included in message

Positive references to race

28% (17)

3% (2)

11% (12)

1% (1)

17% (19)

10% (11)

17% (48)

5% (14)

assigning blame, proposing punishments, questioning societal values, or criticizing parents,

institutions, and/or the youths themselves. Almost 40% of the comments focused on the youths

or their families. Another 28% directed criticism at institutions such as the police, the legal

system, or the media. In addition, 11% criticized society in general or raised questions about

the values of a society in which such incidents could occur (Table 1).

The harshest comments were reserved for the youths and their families. For example, one

person wrote, “I wish this state [had] the death penalty! That way I could go and watch each

and everyone of these punks get FRIED!!” Another person suggested that “each of these boys

should be publicly whipped and then executed on the six o’clock news” and a third noted,

“There may still be hope for the youngest of these criminals, but shoot the 16- and 19-year-old

in the head and save a few tax dollars.”

Relatives of the youths were the targets of similar comments, especially after interviews by

television crews during which one relative blamed the incident on the fact that the boys “were

bored.” In fact, many writers responded to various segments of the televised clips as is the case

with one person who noted, “I am just as pissed at Mom, Auntie, and Gramma for being so

damn stupid. From checking out the tattoos on those ‘babes’ I can assume that they haven’t

spent a lot of time volunteering at the local Boys and Girls’ Clubs. Slimebags.” Another asked

of the parents, “. . . How can you sleep at night? Where were you when your children were out

killing because ‘they were bored?’ How can you even call yourselves parents?” Still another

writer suggested that perhaps it is the relatives who should be punished: “If these brats are too

young to understand that beating a man to death is wrong, then strap their parents into Old

Sparky or put the needle in the parent’s veins.” One other person argued that both the parents

and the youths deserve punishment with the comment,

If these punks are found guilty, their parents should be held financially responsible to all the

victims and their families. These punks should be given the most severe punishment available

by law. We need to purge the EVIL from among us. These thugs are the poster boys for EVIL.

The punk that drop kicked his victim 28 times deserves death in my opinion. His parents deserve

sterilization, so as not to ever produce again such a menace to society . . .

Finally, one individual was more terse but no less blunt in expressing an opinion about the

youths and their families with the words, “IT’S TIME TO HANG THE PARENTS WITH

THEIR CRIMINAL SPAWNS.”

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

7

While forum participants were quick to condemn and while there were numerous calls for

harsh punishment, expressions of sympathy for the victim and/or his family and friends were

limited. In total, only 15 participants, a scant 5% of all messages, expressed some sort of

compassion for those affected by the crime.

Twenty-eight percent of the messages criticized various institutions such as the police department, the news media, or the criminal justice system. Participants complained about the

manner in which the investigation was handled and how the incident was reported. In addition,

some argued that the incident would not have occurred were it not for a lax criminal justice

system that coddles offenders.

For example, one individual wrote, “I only wish our judicial system would finally take a

stand against these ‘KILLERS’ instead of wiping their noses and blaming it on society as a

whole.” Another argued, “This kind of atrocity happens because perpetrators have no ‘fear’

of justice. The ‘judicial system’ has pretty much told them that ‘even if they are caught,’ the

consequences will be modest.”

The media were also criticized for their reporting of the crime with many participants

arguing that The News Tribune was sympathetic toward the youths and their families. The

following is typical of the response to the newspaper’s reporting: “I am personally offended

at the biased reporting your reporters are performing by putting their own spin on this very

tragic . . . incident. The reporters are sympathizing with the families of the thugs who killed

that man.” Others suggested that the newspaper bore some responsibility for the incident. One

person wrote, “Tacoma News Tribine [sic] . . . should share some of the negligence in this

matter. Why didn’t the New’s [sic] Tribune pick up on these beatings and report the news to

the public BEFORE someone was put into a coma by these beatings.”

However, in criticizing institutional behavior some of the strongest words were reserved for

the Tacoma Police Department who, many felt, handled the investigation in a shoddy manner.

One person noted, “Not only do the heads of the guilty party need to roll, but some at Tacoma

P.D. The first one that needs to go is the Chief of Police. What kind of stupid, irresponsible

idiot is this person?” Another wrote, “the chief of police, at best, has a great deal of explaining

to do, and at worst has some of this blood on his hands.” Still another noted, “As a Caucasian

resident of Tacoma I am glad that finally our community gets to see the police sit on their

butts, eating donuts and wasting money. This is nothing new it’s just unfortunate it took this

long because this is what the minority communities have been facing for years.” Yet one more

example of the public’s frustration with local law enforcement is found in the words of the

individual who wrote, “The police make me sick. They described the terror by these punks

as ‘obnoxious behavior,’ and the officer speaking said he was surprised it was youth doing it.

What planet did he come from . . . ”

Finally, 47 of the participants (17% of the total) fell into an “other” category. Typically

these were people who voiced thoughts or opinions only tangentially related to the issue. They

included, for example, calls to embrace religion, demands that citizens’ rights to carry firearms

and protect themselves be preserved, and reports of similar incidents that happened elsewhere.

Race was also a factor in the public’s reaction to the assaults. Prior to the arrests the assailants

were described as a gang of blacks and Hispanics. After arrests were made the media identified

four of the youths as African American, two as Hispanic and two as white. Further, the point

was made that all of their victims were white. These facts served as catalysts for references to

8

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

race in many of the reactions studied. Sixty-two of the forum’s participants (22% of the total)

made some reference to race. About half of these were calls for the youths to be charged with

hate crimes, given that the majority of the offenders were people of color, all of the victims

were white, and the county prosecutor’s indication that the state’s hate-crime statute probably

would not be invoked in this case.

The reactions by those commenting on this element of the case generally reflected a sense

of resentment that hate crimes were not being recognized because of the race/ethnicity of the

youths. In essence, writers charged that a form of reverse discrimination was taking place.

Three examples typify the reactions of those who dwelt on this topic. One person wrote, “I too

want to know why this is a ‘thrill’ crime not a ‘hate’ crime. It seems we label things differently

depending on the race of the victim and/or the criminals.” In a similar vein, a second individual

noted, “It amazes me that this is not being considered a hate crime. If it is against blacks or

other minorities, it is automatically described as such. If its [sic] against whites, it’s considered

a ‘random crime.’ Ah, political correctness!” A third writer was more forceful in noting, “I am

fed up here. Every time a black gets beat up or stoped [sic] by the cops . . . it’s racial. But if a

white gets beat to death . . . it’s not. I say bull.”

About 28% of the writers of race-related comments ignored the hate-crime issue but directed

racial invective against the youths or society at large. In some instances the comments were

overtly racist. For example, one individual wrote, “. . . Until the minorities who spawned these

murdering scum take responsibility to clean up the miscreants who commit such crimes and

stop making excuses for their sorry conduct, this type of nonsense is not going to stop.”

Others were equally racist but employed other techniques to make their points, as illustrated

by the following attempt at sarcasm:

Come on people! Let’s not be prejudiced! That the 10 or more victims were white is just a

corny coincidence. I’m sure if they could have found any black people . . . during that time they

would of beat them up too. As for [the victim] if he had been black I’m sure [the offenders]

would have done 28 knee-drops to HIS unconscious face too . . . .

In other instances racist comments were directed further afield. For example, one person

asked, “How soon can we expect The Rev. Al Sharpton and perhaps Johnny Corchran [sic]

or the likes to pervert justice and Tacoma tax payers end up with a multi-million dollar law

suit?” Similarly, another writer noted, “If these 10 attacks happened to any other race other

than white, we would have the likes of Jessie Jackson’s face on the news every day for a

month—screaming for justice . . . ” And yet a third said,

If [the police] would have warned the neighborhood ‘watch out for a group . . . made up of

mostly blacks and Hispanics’ the ACLU, the NACCP [sic] would have been all over them. Sure

a white guy died as a result of their political decision . . . since he is white, there is no interest

group to make him their cause celebre. If you are not part of a ‘protected class’ in America in

2000, then you better get used to this.

One other forum participant sought to stereotype the broader African-American community

in noting “. . . minority children are taught . . . that Honkies [have been] out to get them . . .

for so long that they are basically free to do whatever, whenever they want . . . .”

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

9

Finally, only a small number of people who injected race into the proceedings did so in

a positive manner. Of the 62 messages dealing with race, 14 (22%) were calls for racial

understanding or pleas to tone down the racist rhetoric that was appearing in the forum.

4. Discussion

The first finding in this study that we believe merits discussion is the overwhelming number

of critical posts. While the criticism was directed at several sources ranging from the youth

and their parents to institutions like the media and the police, the harsh nature of the posts

suggests that the web forum was an outlet for people’s anger, outrage, and frustration over the

attacks. Because it was the newspaper that sponsored the forum, it stands to reason that those

who posted comments did so after reading stories in The News Tribune since that was the only

place where the forum was advertised. The events and the media’s coverage of them elicited

emotional reactions in people which were then expressed in the forum. However, the manner

in which this was done, we believe, is significant to our understanding of the Internet as a site

for community building and meaningful interaction.

While the percentage of critical posts is noteworthy, so too is their focus. The majority

of critical posts were focused on the youths and/or their families and, as the examples in

the findings section imply, many of these comments were extreme in the way they expressed

sentiments of revenge, retribution, and vigilante-like ideas. In contrast, a public meeting held

while the forum was ongoing and attended by some 400 to 500 community residents was

notable for the lack of vigilante rhetoric or threats of revenge. There were neither the extreme

calls for retribution nor the racist comments that were offered up in the web forum.

The differences between the comments at the public meeting and those on the newspaper’s

forum can be related to the format of each. The web forum permitted anonymity with no

social constraints on reactions to the incident, language used, or attitudes expressed. However, the community meeting was organized and moderated by the Tacoma Police Department.

A large police presence was evident, it had a 2-hr time limit, a police officer opened the

discussion and spoke for the first half-hour, television cameras were present, the police specifically called for tolerance of differing viewpoints, and speakers were required to state their

names.

During the public meeting there was criticism of the police, there were calls for accountability, and the parents of the youths were criticized. However, the criticism was muted and it was

expressed in civil tones. Further, pleas for racial understanding, expressions of concern for the

community, and calls for finding solutions to violence of this nature dominated the meeting.

Race as a potentially controversial issue was introduced only once. In response to a speaker’s

request that the police and the public avoid “racial profiling” in reacting to the incident a person

in the audience noted that it was the youths who had engaged in racial profiling. Clearly the

format of the meeting, the approach adopted by the majority of speakers, and the presence of

the police and the media affected the tenor of the gathering and created a distinctly different

response to the matter than was the case on the Internet.

Admittedly, communication in the physical presence of others is not necessarily the more

productive or more positive form of discourse given that “face-to-face interaction does not

10

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

necessarily break down boundaries, and to adopt it as an ideal will likewise not necessarily

facilitate communication, community building, or understanding among people” (Jones, 1998,

p. 26). However, communication in the physical presence of others does tend to bring about

restraint and, in many cases, a tempering of the words used to make points.

We also found that the information released each day in both the print and broadcast media

tended to influence the content and nature of these responses. For example, on the first day The

News Tribune reported the arrests they referred to the assaults as “thrill crimes” but the specific

details of the attack on Mr. Toews were not included. On that day 28% of posts blamed or

criticized the youths and/or their families. On the second day the graphic details of the attack

on Toews contained in the court papers were printed in the paper and reported on television.

These details included the “28 knee drops” that led to Mr. Toews’ death and a comment by

a grandmother of one of the suspects that explained away the youth’s behavior as the result

of boredom. The forum participants reacted strongly to this. Postings that expressed anger or

called for punishment of the youths and/or their families increased to 48%. Much of this anger

lingered into the third day when 35% of all posts in the forum called for retribution/punishment

or criticized the youths and/or their families. In sum, we see a significant correlation between

the content of the stories in The News Tribune each day and the tone and content exhibited in

the web forum posts.

Another interesting finding is that a small percentage of the posts that we categorized as

“Other” involved instances where people used the forum as a vehicle to promote specific

agendas that were not directly related to the attack. For example, several people used the

forum to argue against gun control suggesting that if Mr. Toews (or any of the other victims)

had been armed then the attacks could have prevented. Others used the forum to promote

religious views and in one instance, the forum was used to recruit members for a known hate

group. This evidence suggests that some individuals used the web forum to advertise and/or

promote their own religious and political agendas with little regard for the specific issue at

hand.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of this forum was the degree to which racist attitudes were

expressed. Nearly 20% of all the posts during the 3-day period addressed race in a negative

fashion. Sixty percent of those posts called attention to the issue of hate crimes. In these

instances forum participants complained that a double standard was being used in determining

what constituted a hate crime. In general, they argued that the criminal justice system favored

minorities in designating when a hate crime had been committed. The remaining 40% of the

race-negative posts were much more extreme in the manner in which they exhibited racial

bias. In some cases all people of color were characterized in negative ways. In other instances

the families of the youths were depicted in harsh racial terms. This sort of reaction was not

found in the public meeting. Nevertheless, this does not mean that many in attendance did not

harbor feelings of ill-will toward people of color. If such feelings existed among those in the

audience they were likely not expressed because of the constraints of identity, media and police

presence, and the face-to-face venue of the event. However, it is argued that the anonymity

the Internet affords gives prejudiced people license to publicly express racist attitudes. This

contention is reinforced by the fact that only 25% of those who expressed negative racial views

in this forum included their email address as a part of their post, while 53% of all other forum

participants included theirs. This discrepancy suggests that the majority of those individuals

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

11

who expressed such prejudicial attitudes did so only because they could remain completely

anonymous.

Along similar lines, only 5% of forum participants expressed sympathy for the victims and

their friends and families. Again, in the public forum where individuals had to stand in one

another’s presence, calls for racial understanding and sympathy were a more common theme

espoused by those who spoke at the event. That the reverse is true in cyberspace reinforces

the notion that discussants in Internet forums are more willing to use the Internet to express

extreme social and political viewpoints.

One final finding we believe is noteworthy is that initially the forum was not used as a

means for the participants to interact and/or respond to one another. For example, on the first

day only five people could be identified as repeat users and only 8 or 11% of the postings either

referred to other posts or invited others to respond. A similar situation is found on the second

day when there were nine repeat users and only four of the posts invited others to respond

directly. However, this changed markedly on the third day when 30% of all posts were from

repeat users. Also on the third day, 64 or 37% of all posts were what we consider responsive

or interactive in nature—that is, they built on an idea presented in another post, responded to

a point made by someone else, or asked another participant a question.

This lack of interactivity during the first 2 days of the forum is somewhat perplexing. We

believe a number of things may explain this. It may be that no themes or particular subjects

emerged that prompted or invited direct responses from others. It also might be that in forums

such as this people initially post a message to express anger or to emote in some fashion, and

only after the immediacy of the emotions subsides are people more willing to engage with

others. On the other hand, it might be that forum participants wait to see what themes or lines

of thought repeatedly surface in the forum before they begin to respond directly to others. And

finally, some individuals may wait to see who the repeat users are. For instance, on day 3 we

found that repeat posters returned to the forum at different times throughout the day to view the

comments and submit additional posts. Repeat postings by the same individual often appeared

several hours apart. The fact that on the third day users begin returning to the forum on a regular

basis and posting additional comments is an interesting phenomenon. In essence, individuals

are now making the forum a part of their day. They are repeatedly drawn to the site and make it

a point to express additional thoughts. It may be that for a small group of users the forum begins

to take on the characteristics of a “soap opera” in which they are permitted to participate. Who

these people are and why they adopt this approach on the third day is something that deserves

further investigation. Further, the final hours of the forum were dominated by a select group of

repeat users who had, at that point, begun to monopolize the forum for their own conversations.

For example, approximately 50% of all repeat posts for day three appeared during the final two

hours of the forum. During this time thirteen individuals were repeat posters. However, three

individuals accounted for two-thirds of these posts. During the final few hours the repeat posters

did not verbally attack one another. However, they did carry on socially divisive and, in part,

racially-charged dialogue. Further, none of these participants included their email addresses.

The fact that it took so long for interaction to take place over this highly-charged issue and the

fact that those who participated chose to remain anonymous from one another merit further

inquiry on the part of those who seek to better understand the dynamics of interactions in

cyberspace.

12

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

5. Conclusions

The role of the electronic forum as a vehicle for constructive dialogue to promote understanding and to address community concerns appears to be limited in certain situations. Indeed,

in some instances, such forums are counter-productive to their stated purposes. This may well

be the case when the topic is likely to have raised the ire of many in the community, as did the

senseless killing of Mr. Toews. The forum analyzed in this study was intended as an outlet for

concern, a vehicle to express sorrow and sympathy, and a means to let people try and understand why the incident took place and how such incidents might be prevented in the future. In

short, it was intended to bring people together. However, the volatile topics of race and crime

coupled with the anonymity of the Internet served to create something entirely different. What

emerged was a series of vitriolic, argumentative, and racist denunciations of the youths, their

families, and various socio-political institutions.

Communication in the physical presence of others carries with it restraints. In some fashion,

those listening to us hold us accountable for what we say. We are aware of this and structure

our conversations and behavior accordingly (Goffman, 1959). Electronic communication, in

large part, removes those constraints. Furthermore, passions are often fueled by what others

say. Forums are often unmonitored and, hence, uncensored. When people see others expressing

extreme or outlandish views they may be less inhibited in expressing their own sentiments in

equally strong terms. This appears to be particularly true for short-term forums where no sense

of “virtual community” develops since participants do not have the opportunity to get to know

one another over an extended period of time.

In some cases the web forum appears to do little to help people come to terms with an

adverse event. Clearly this is the case when people aired thoughts about the death of Eric

Toews. It would be difficult to argue that this particular forum brought people together in

any meaningful way. Rather, the manner in which the forum was used was socially divisive.

The impact of this is magnified by the fact that the forum was sponsored by the community’s

leading news organization. This lent some degree of credibility to the forum, it no doubt

increased readership/authorship, and it may well have led to the impression that the sentiments

expressed in the forum were reflective of the general public in much the same way that “letters

to the editor” are judged to reflect the public’s views.

However, only a fraction of letters to editors are ever printed, they are not anonymous,

and extreme or volatile language rarely appears on opinion pages. In the case of unmonitored

forums the writers are usually unknown. We do not know their ages, their backgrounds, or their

places of residence—nor can we easily find these things out. Thus, the forum becomes a means

of expression for people who otherwise would not (and in many cases probably should not)

be heard. This is not to suggest that forums such as these should be discontinued. However,

media outlets may wish to give more consideration to the types of topics selected to promote

community understanding and dialogue.

Moreover, while we do not advocate censorship, we do think some monitoring of the content

of web forums is in order. One option available to media organizations is asking participants

to register as forum users. Such an approach may serve to temper the content of postings and

reinstate the social constraints that are otherwise absent in electronic communication of this

sort. We do not believe a registration requirement compromises the free speech aspects of

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

13

Internet forums. In such instances participants still have the right to express their viewpoints,

however outlandish. Further, they continue to remain anonymous to other posters. The only

thing that registration does is reveal the identity of forum users to a small, non-participating

group (i.e., the site’s webmasters). This will introduce a level of “social presence” that is well

below that of face-to-face communication but more than is found in completely anonymous

electronic communication (see, for example, Gackenbach, 1998, p. 50). The introduction of this

low level of “constraint” may well serve to improve the dialogue associated with controversial

and emotional topics.

This case study suggests that in some instances the potential for Internet web forums to

serve as sites for the exchange of effective, positive, and constructive ideas is limited. Rather

than fostering honest and meaningful dialogue among individuals affected by a disturbing

and racially-charged incident in their city, this study has shown that the forum was actually used by participants to subvert the very possibility of this occurring. While we take

some comfort in knowing that there were individuals who challenged the tone and content of overtly racist messages posted in the forum, they were clearly in the minority. The

civility, empathy, and reasoned commentary so important to the substance of any democracy existed only on the forum’s fringe as the majority of participants sought to use the

forum to blame and criticize while sometimes advancing their own extreme beliefs behind

the veil of anonymity. We are reminded here of the work of legal scholar Stephen Carter

who, in his treatise on civility, describes an “etiquette of democracy” that “requires that we

express ourselves in ways that demonstrate our respect for others” (Carter, 1998, p. 282).

There were few instances of such democratic mannerisms at work in The News Tribune’s web

forum.

The case also raises a number of prospects for further research. For example, the difference

between long-term and short-term forums merits further attention. Is there less likelihood of

extremism within ongoing cyber-communities or does it depend on the topic being considered?

Another avenue for exploration is the question of place. Are people more likely to respond

more vigorously to an incident or issue that is local rather than something from which they are

further removed? In other words, is there a distance-bias that affects rhetoric when coupled

with the anonymity of cyberspace? Finally, the matter of anonymity versus identification is one

that merits more study. When people identify themselves in some respect (e.g., by registering

to be part of a forum or by including an email address) does this make them less likely to

engage in rhetoric that people find offensive? Findings from such work may be of value in

promoting civility and community in cyberspace.

Finally, if one sought to find something positive about the role of a web forum such as

this, it might be argued that, while the forum was a depository for expressions of rage, the

mere act of making such pronouncements (e.g., “there is no way that you fix these worthless

idiots . . . get THEM off the face of the earth . . . to [sic] bad we can’t do their families

in too”) may have, in some small way, allowed forum participants to release themselves

of the immediacy of their emotions. This, in turn, may have decreased the possibility of

their pursuing an even more extreme response to this incident. Should this have been the

case, we still find little comfort in the potential of cyber venues like this to promote understanding and further community discourse when they deal with volatile and emotional social

issues.

14

B. Coffey, S. Woolworth / The Social Science Journal 41 (2004) 1–14

References

Baym, N. (1998). The emergence of community in computer-mediated communication. In S. Jones (Ed.),

Cybersociety (pp. 138–163). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1996). Habits of the heart: Individualism

and commitment in American life (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Benson, T. (1996). Rhetoric, civility, and community: Political debate on computer bulletin boards. Communication

Quarterly, 44(3), 359–378.

Burns, S. (2000a, August 30). Eight arrested in thrill beatings; 7 boys, 1 man suspects in spree that killed Tacoma

man. The News Tribune (pp. A1, A16).

Burns, S. (2000b, August 26). Man dies from beating injuries. The News Tribune (p. A1).

Burns, S. (2001, January 22). Arrests made in all homicide cases from 2000. The News Tribune (p. A8).

Carter, S. L. (1998). Civility: Manners, morals, and the etiquette of democracy. New York: Basic Books.

Gackenbach, J. (Ed.). (1998). Psychology and the Internet. San Diego: Academic Press.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday.

Jones, S. (1998). Information, Internet, and community: Notes toward an understanding of community in the

information age. In S. Jones (Ed.), Cybersociety 2.0: Revisiting computer-mediated communication and

community (pp.1–34). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Myers, D. (1987). ‘Anonymity is part of the magic’: Individual manipulation of computer-mediated communication

contexts. Qualitative Sociology, 19(3), 251–266.

Nguyen, D. T., & Alexander, J. (1996). The coming of cyberspacetime and the end of the polity. In R. Shields (Ed.),

Cultures of the Internet (pp. 99–124). London: Sage Publications.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Reid, C., & Gillie, J. (2000, August 31). Grief, anger spill out; 2 suspects plead not guilty to murder in court

appearance. The News Tribune (p. A1).

Schultz, T. (2000). Mass media and the concept of interactivity: An exploratory study of online forums and reader

email. Media, Culture & Society, 22(2), 205–221.

Smith, M. A., & Kollock, P. (Eds.). (1999). Communities in cyberspace. London: Routeledge.

Walther, J. B. (1992). Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated interaction. Communication Research, 19(1),

52–90.