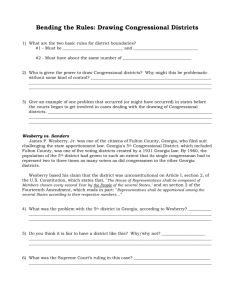

White Challengers, Black Majorities

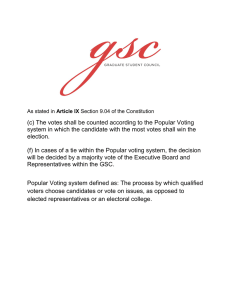

advertisement