Curriculum Development - International Baccalaureate

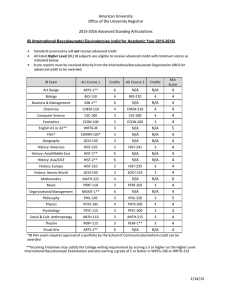

advertisement