Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America

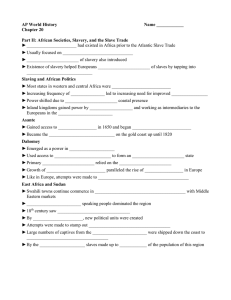

advertisement