Child Safety Online

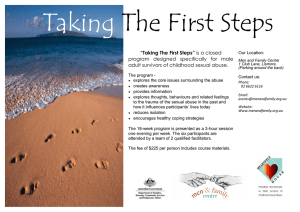

advertisement