University of Iowa

Iowa Research Online

Theses and Dissertations

Spring 2014

Enhancing communicative interaction by training

peers of children with autism

Sarah Marie Labaz

University of Iowa

Copyright 2014 Sarah Marie Labaz

This dissertation is available at Iowa Research Online: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/4673

Recommended Citation

Labaz, Sarah Marie. "Enhancing communicative interaction by training peers of children with autism." MA (Master of Arts) thesis,

University of Iowa, 2014.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/4673.

Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd

Part of the Speech Pathology and Audiology Commons

ENHANCING COMMUNICATIVE INTERACTION BY TRAINING PEERS OF

CHILDREN WITH AUTISM

by

Sarah Marie Labaz

A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment

of the requirements for the

Master of Arts degree in Speech Pathology and Audiology

in the Graduate College of

The University of Iowa

May 2014

Thesis Supervisor: Professor Richard R. Hurtig

Copyright by

SARAH MARIE LABAZ

2014

All Rights Reserved

Graduate College

The University of Iowa

Iowa City, Iowa

CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL

_______________________

MASTER'S THESIS

_______________

This is to certify that the Master's thesis of

Sarah Marie Labaz

has been approved by the Examining Committee

for the thesis requirement for the Master of Arts degree

in Speech Pathology and Audiology at the May 2014 graduation.

Thesis Committee: __________________________________

Richard R. Hurtig, Thesis Supervisor

__________________________________

Karla McGregor

__________________________________

Elizabeth Delsandro

To my mentor Richard Hurtig, who has become much more than a thesis supervisor to

me. Thank you for your patience, your wisdom, and for molding my passion of AAC.

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank my committee members, Elizabeth Delsandro and Karla

McGregor, for their expertise and time. It is truly an honor to be surrounded by such

innovative and passionate individuals within the field of speech-language pathology.

A special thanks is given to Lauren Zubow, for her ideas, guidance, and

tremendous amount of time given to this thesis. I credit the basis and success of this

project to her ingenuity.

I would like to acknowledge and thank Lauren Lichty and Beth Weis, the lead

teachers in the KidTalk preschools, for their flexibility and willingness in allowing me to

come into their classrooms and interact with their students.

iii

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to assess the effectiveness of training preschool-aged

children to support the communication of their peers with autism spectrum

disorder. Four typically developing peers participated in a 12-week training study that

consisted of video models, social narratives, and practice opportunities. The peers were

taught to implement the strategies “show, wait, and tell” with a classmate with autism

during play. Peers were also provided with instruction to make them more aware of

communication via augmentative modalities and to understand the Pragmatically

Organized Dynamic Display (PODD) that the classmate with autism used to

communicate. A second child with autism served as a control subject to measure

generalization of the training to other children with autism. The study also included a

group of four control peers who received no training in order to distinguish the effect of

the training from normal communicative and social developmental that one might see

over the time of the study. All play sessions were video recorded and coded utilizing a

coding system that identified verbal and nonverbal behaviors of the peers and the

children with autism. 3 of the 4 trained peers demonstrated the ability or willingness or

implement the targeted strategies with the target child with autism. A single trained peer

generalized the use of the trained strategies when interacting with to the control

subject. Peers performed best when provided with clinician cues to implement

strategies. Both children with autism increased their communication and interaction with

trained peers during play when compared with their interactions with the control

peers. Furthermore, the children with autism interacted maximally during sessions in

which the trained peers utilized the communication strategies These results provide

preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of preschool peer training to support the

communication of children with autism.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. ix

LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ x

CHAPTER

I.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ................................................................. 1

II.

METHODS .................................................................................................... 11

Participants .................................................................................................... 11

Training Subject ..................................................................................... 11

Control Subject ....................................................................................... 11

Training Peers ......................................................................................... 12

Control Peers .......................................................................................... 12

Consent .......................................................................................................... 13

Training Content ............................................................................................ 13

Protocol .......................................................................................................... 15

Training Peers ......................................................................................... 19

Control Peers .......................................................................................... 21

Training Subject ..................................................................................... 22

Control Subject ....................................................................................... 23

Data Analysis ................................................................................................. 23

Reliability Coding .......................................................................................... 26

III.

RESULTS ...................................................................................................... 28

Control Peers with Peers ................................................................................ 28

Control Peer 1 ......................................................................................... 28

C1 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 28

C1 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 29

C1 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 30

Control Peer 2 ......................................................................................... 30

C2 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 30

C2 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 31

C2 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 32

Control Peer 3 ......................................................................................... 32

C3 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 32

C3 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 33

C3 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 34

Control Peer 4 ......................................................................................... 35

C4 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 35

C4 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 35

C4 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 36

Control Peer Group 1 (Control Peer 1 & Control Peer 2) ...................... 37

CP1 Averaged Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................ 37

CP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers .......................................... 37

CP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers .............................. 38

Control Peer Group 2 (Control Peer 3 & Control Peer 4) ...................... 39

v

CP2 Averaged Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................ 39

CP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers .......................................... 39

CP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers .............................. 40

All Control Peers .................................................................................... 41

Control Peer Averaged Behaviors ................................................... 41

Control Peer Averaged Strategy Use ............................................... 41

Control Peer Averaged Strategy Breakdown .................................. 42

Control Peers with Target & Control Subject................................................ 43

Control Peer 1 ......................................................................................... 43

C1 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 43

C1 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 44

C1 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 45

Control Peer 2 ......................................................................................... 46

C2 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 46

C2 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 46

C2 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 47

Control Peer 3 ......................................................................................... 48

C3 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 48

C3 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 49

C3 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 50

Control Peer 4 ......................................................................................... 51

C4 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 51

C4 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 51

C4 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 52

Control Peer Group 1 (Control Peer 1 & Control Peer 2) ...................... 53

CP1 Averaged Behaviors to Subjects Over Time ........................... 53

CP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ..................................... 53

CP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ......................... 54

Control Peer Group 2 (Control Peer 3 & Control Peer 4) ...................... 55

CP2 Averaged Behaviors to Subjects Over Time ........................... 55

CP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ..................................... 55

CP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ......................... 56

All Control Peers .................................................................................... 57

Control Peer Averaged Behaviors with Subjects ............................ 57

Control Peer Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ........................ 57

Control Peer Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............ 58

Trained Peers ................................................................................................. 59

Training.......................................................................................................... 59

Trained Peer 1 ......................................................................................... 59

Clinician Input to T1 ....................................................................... 59

Clinician Cues to T1 ........................................................................ 60

Trained Peer 2......................................................................................... 61

Clinician Input to T2 ....................................................................... 61

Clinician Cues to T2 ........................................................................ 62

Trained Peer 3......................................................................................... 63

Clinician Input to T3 ....................................................................... 63

Clinician Cues to T3 ........................................................................ 64

Trained Peer 4......................................................................................... 65

Clinician Input to T4 ....................................................................... 65

Clinician Cues to T4 ........................................................................ 65

All Trained Peers .................................................................................... 66

Clinician Input to all Trained Peers ................................................. 66

Clinician Cues to all Trained Peers ................................................. 67

Trained Peers with Peers ............................................................................... 68

vi

Trained Peer 1 ......................................................................................... 69

T1 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 69

T1 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 69

T1 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 70

Trained Peer 2......................................................................................... 71

T2 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 71

T2 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 71

T2 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 72

Trained Peer 3......................................................................................... 73

T3 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 73

T3 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 73

T3 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 74

Trained Peer 4......................................................................................... 75

T4 Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................................... 75

T4 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................... 75

T4 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................. 76

Trained Peer Group 1 (Trained Peer 1 & Trained Peer 2)...................... 77

TP1 Averaged Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................ 77

TP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers........................................... 77

TP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers .............................. 78

Trained Peer Group 2 (Trained Peer 3 & Trained Peer 4)...................... 79

TP2 Averaged Behaviors to Peers Over Time ................................ 79

TP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers........................................... 79

TP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers .............................. 80

All Trained Peers .................................................................................... 81

Trained Peer Averaged Behaviors ................................................... 81

Trained Peer Averaged Strategy Use .............................................. 81

Trained Peer Averaged Strategy Breakdown .................................. 82

Trained Peers with Subjects........................................................................... 83

Trained Peer 1 ......................................................................................... 84

T1 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 85

T1 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 85

T1 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 85

Trained Peer 2......................................................................................... 86

T2 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 86

T2 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 87

T2 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 88

Trained Peer 3......................................................................................... 89

T3 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 89

T3 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 89

T3 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 90

Trained Peer 4......................................................................................... 91

T4 Behaviors to Subjects Over Time .............................................. 91

T4 Total Strategy Use with Subjects ............................................... 92

T4 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ............................................ 93

Trained Peer Group 1 (Trained Peer 1 & Trained Peer 2)...................... 94

TP1 Averaged Behaviors to Subjects Over Time............................ 94

TP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................... 94

TP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ......................... 95

Trained Peer Group 2 (Trained Peer 3 & Trained Peer 4)...................... 96

TP2 Averaged Behaviors to Subjects Over Time............................ 96

TP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................... 97

TP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ......................... 98

All Trained Peers .................................................................................... 99

vii

Trained Peer Averaged Behaviors with Subjects ............................ 99

Trained Peer Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ........................ 99

Trained Peer Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects.......... 100

Control Subject ............................................................................................ 101

Control Subject with Control Peers ...................................................... 102

CS Behaviors with C1 & C2 ......................................................... 102

CS Behaviors with C3 & C4 ......................................................... 102

Control Subject with Trained Peers ...................................................... 103

CS Behaviors with T1 & T2 .......................................................... 103

CS Behaviors with T3 & T4 .......................................................... 104

Target Subject .............................................................................................. 105

Target Subject with Control Peers ........................................................ 105

TS Behaviors with C1 & C2 .......................................................... 105

TS Behaviors with C3 & C4 .......................................................... 105

Target Subject with Trained Peers ....................................................... 106

TS Behaviors with T1 & T2 .......................................................... 106

TS Behaviors with T3 & T4 .......................................................... 106

IV.

DISCUSSION .............................................................................................. 108

Qualitative Results ....................................................................................... 108

Control Peers with Subjects.................................................................. 108

Trained Peers with Subjects ................................................................. 109

Interaction ...................................................................................... 109

Strategies ....................................................................................... 109

Target Subject Behavior ....................................................................... 111

Control Subject Behavior ..................................................................... 113

Classroom Dynamics ................................................................................... 113

Personality Differences ................................................................................ 115

Training........................................................................................................ 117

Limitations ................................................................................................... 118

Future Directions ......................................................................................... 119

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................... 121

APPENDIX

A.

SOCIAL NARRATIVE “SOME KIDS USE PICTURE BOARDS TO

TALK” ......................................................................................................... 124

B.

SOCIAL NARRATIVE “IT CAN BE FUN WHEN EVERYONE

PLAYS TOGETHER” ................................................................................. 135

C.

RELIABILITY CODER INSTRUCTIONS ................................................ 146

D.

RELIABILITY CODER CODE DESCRIPTIONS ..................................... 148

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1 Participant Codes .............................................................................................. 16

Table 2.2 Participant Group Codes ................................................................................... 17

Table 2.3 Session Codes ................................................................................................... 17

Table 2.4 Outline of Protocol for Each Participant........................................................... 18

Table 2.5 Outline of Analyzed Behaviors......................................................................... 25

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1 Screen shot from the video of researcher modeled PODD use ....................... 14

Figure 2.2 ELAN tiered template used for data analysis .................................................. 24

Figure 3.1 C1 Behaviors to Peers ..................................................................................... 29

Figure 3.2 C1 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................... 29

Figure 3.3 C1 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................................. 30

Figure 3.4 C2 Behaviors to Peers ..................................................................................... 31

Figure 3.5 C2 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................... 31

Figure 3.6 C2 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................................. 32

Figure 3.7 C3 Behaviors to Peers ..................................................................................... 33

Figure 3.8 C3 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................... 34

Figure 3.9 C3 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ................................................................. 34

Figure 3.10 C4 Behaviors to Peers ................................................................................... 35

Figure 3.11 C4 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................. 36

Figure 3.12 C4 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................................... 36

Figure 3.13 CP1 Averaged Behaviors to Peers ................................................................. 37

Figure 3.14 CP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers ........................................................ 38

Figure 3.15 CP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................ 38

Figure 3.16 CP2 Averaged Behaviors to Peers ................................................................. 39

Figure 3.17 CP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers ........................................................ 40

Figure 3.18 CP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................ 40

Figure 3.19 CP Averaged Behaviors with Peers ............................................................... 41

Figure 3.20 CP Averaged Strategy Use with Peers .......................................................... 42

Figure 3.21 CP Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers .............................................. 43

Figure 3.22 Percentages of C1 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 44

Figure 3.23 C1 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 45

x

Figure 3.24 C1 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 45

Figure 3.25 Percentages of C2 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 46

Figure 3.26 C2 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 47

Figure 3.27 C2 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 48

Figure 3.28 Percentages of C3 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 49

Figure 3.29 C3 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 50

Figure 3.30 C3 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 50

Figure 3.31 Percentages of C4 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 51

Figure 3.32 C4 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 52

Figure 3.33 C4 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 52

Figure 3.34 Averaged Percentages of CP1 Behaviors to Subjects ................................... 53

Figure 3.35 CP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ................................................... 54

Figure 3.36 CP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ....................................... 54

Figure 3.37 Averaged Percentages of CP2 Behaviors to Subjects ................................... 55

Figure 3.38 CP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects ................................................... 56

Figure 3.39 CP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ....................................... 56

Figure 3.40 Averaged Percentages of All CP Behaviors with Subjects ........................... 57

Figure 3.41 Averaged CP Strategy Use with Subjects ..................................................... 58

Figure 3.42 Averaged CP Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ......................................... 58

Figure 3.43 Clinician Input to T1 ..................................................................................... 60

Figure 3.44 Clinician Cues to T1 ...................................................................................... 61

Figure 3.45 Clinician Input to T2 ..................................................................................... 62

Figure 3.46 Clinician Cues to T2 ...................................................................................... 63

Figure 3.47 Clinician Input to T3 ..................................................................................... 64

Figure 3.48 Clinician Cues to T3 ...................................................................................... 64

Figure 3.49 Clinician Input to T4 ..................................................................................... 65

Figure 3.50 Clinician Cues to T4 ...................................................................................... 66

xi

Figure 3.51 Clinician Input to All Trained Peers .............................................................. 67

Figure 3.52 Clinician Cues to All Trained Peers .............................................................. 68

Figure 3.53 T1 Total Behaviors to Peers .......................................................................... 69

Figure 3.54 T1 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................. 70

Figure 3.55 T1 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................................... 70

Figure 3.56 T2 Total Behaviors to Peers .......................................................................... 71

Figure 3.57 T2 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................. 72

Figure 3.58 T2 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................................... 72

Figure 3.59 T3 Total Behaviors to Peers .......................................................................... 73

Figure 3.60 T3 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................. 74

Figure 3.61 T3 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................................... 74

Figure 3.62 T4 Total Behaviors to Peers .......................................................................... 75

Figure 3.63 T4 Total Strategy Use with Peers .................................................................. 76

Figure 3.64 T4 Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................................... 76

Figure 3.65 TP1 Averaged Behaviors to Peers Over Time .............................................. 77

Figure 3.66 TP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers......................................................... 78

Figure 3.67 TP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................ 78

Figure 3.68 TP2 Averaged Behaviors to Peers Over Time .............................................. 79

Figure 3.69 TP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Peers......................................................... 80

Figure 3.70 TP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Peers ............................................ 80

Figure 3.71 Trained Peers Averaged Behaviors ............................................................... 81

Figure 3.72 Trained Peer Averaged Strategy Use ............................................................ 82

Figure 3.73 Trained Peer Averaged Strategy Breakdown ................................................ 83

Figure 3.74 Percentages of T1 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 84

Figure 3.75 T1 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 85

Figure 3.76 T1 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 86

Figure 3.77 Percentages of T2 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 87

xii

Figure 3.78 T2 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 88

Figure 3.79 T2 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 88

Figure 3.80 Percentages of T3 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 89

Figure 3.81 T3 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 90

Figure 3.82 T3 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 91

Figure 3.83 Percentages of T4 Behaviors to Subjects ...................................................... 92

Figure 3.84 T4 Strategy Use with Subjects ...................................................................... 93

Figure 3.85 T4 Strategy Breakdown with Subjects .......................................................... 93

Figure 3.86 TP1 Averaged Percentage of Behaviors to Subjects ..................................... 94

Figure 3.87 TP1 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects .................................................... 95

Figure 3.88 TP1 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ....................................... 96

Figure 3.89 TP2 Averaged Percentage of Behaviors to Subjects ..................................... 97

Figure 3.90 TP2 Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects .................................................... 98

Figure 3.91 TP2 Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ....................................... 98

Figure 3.92 All TP Averaged Percentage of Behaviors to Subjects ................................. 99

Figure 3.93 TP Averaged Strategy Use with Subjects .................................................... 100

Figure 3.94 TP Averaged Strategy Breakdown with Subjects ....................................... 101

Figure 3.95 CS Behaviors with C1 & C2 ....................................................................... 102

Figure 3.96 CS Behaviors with C3 & C4 ....................................................................... 103

Figure 3.97 CS Behaviors with T1 & T2 ........................................................................ 104

Figure 3.98 CS Behaviors with T3 & T4 ........................................................................ 104

Figure 3.99 TS Behaviors with C1 & C2 ........................................................................ 105

Figure 3.100 TS Behaviors with T1 & T2 ...................................................................... 106

Figure 3.101 TS Behaviors with T3 & T4 ...................................................................... 107

Figure A1: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 1 ........................................ 124

Figure A2: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 2 ........................................ 125

Figure A3: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 3 ........................................ 126

xiii

Figure A4: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 4 ........................................ 127

Figure A5: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 5 ........................................ 128

Figure A6: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 6 ........................................ 129

Figure A7: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 7 ........................................ 130

Figure A8: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 8 ........................................ 131

Figure A9: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 9 ........................................ 132

Figure A10: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 10 .................................... 133

Figure A11: “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to Talk,” page 11 .................................... 134

Figure B1: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 1 ............................ 135

Figure B2: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 2 ............................ 136

Figure B3: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 3 ............................ 137

Figure B4: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 4 ............................ 138

Figure B5: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 5 ............................ 139

Figure B6: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 6 ............................ 140

Figure B7: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 7 ............................ 141

Figure B8: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 8 ............................ 142

Figure B9: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 9 ............................ 143

Figure B10: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 10 ........................ 144

Figure B11: “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together,” page 11 ........................ 145

xiv

1 CHAPTER I

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Preschool is a time of rapid growth and development of a multitude of skills and

abilities. One crucial skill developed in preschool is the ability to form friendships and

interact socially. Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) who use

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) have differences in a variety of

areas that may result in difficulty communicating with peers. This difficulty often results

in communication primarily with teachers during the school day (King & Fahsl, 2012).

These factors contribute to limited peer communication, further hindering the

development of friendship. Peer training interventions offer a way to break this cycle,

and have been used successfully to increase social interactions between children with and

without ASD using AAC (Banda, Hart, & Liu-Gitz, 2010).

Peer relationships are important for healthy development from preschool through

adulthood. Overtime, peer relationships contribute to a child’s identity and self-worth.

Research has shown that peer interactions can enhance the language abilities of children

with disabilities (McGregor, 2000). Many children with ASD have impairments in

communication that may negatively impact the formation of friendships with peers.

Often, children with ASD have difficulty establishing joint attention, initiating

interactions, responding to peer attempts for interaction, and maintaining conversation

(Rotheram-Fuller & Kasari, 2011). These communication impairments require partners

to meet the child with ASD more than half way, a potential challenge for young

playmates.

In addition to communication, children with ASD have behavioral differences that

can impact the development of friendships. Often children with ASD have focused

interests or perseverative behaviors. These high interests make it difficult for children

with ASD to change topic or activity per peer request. Furthermore, disruptive or

undesirable behaviors may impact a peer’s desire to approach and engage a child with

2 ASD (Rotheram-Fuller & Kasari, 2011). Notably, Rotheram-Fuller (2005) showed that

children with ASD in inclusive classrooms are more likely to be included by peers at

younger ages than at older ages. It was hypothesized by the authors that younger children

are more open to the differences amongst peers.

A crucial piece that must develop to form friendships is Theory of Mind (ToM),

or the ability to understand and interpret the thoughts and feelings of others. ToM helps

children anticipate other’s interactions and modify their own behavior to maximize social

interaction. ToM begins developing as young as 6 months, but starts to really emerge

and become defined between 4-5 years of age (Eggum, Eisenberg, Kao, Spinrad, Bolnick,

Hofer, Kupfer, & Fabricius, 2010). A stepping-stone in the development of ToM is joint

attention and pretend play. Joint attention, a skill often lacking in children with ASD,

emerges in typically developing children around 6 months of age. Pretend play, is

typically first seen between 30-36 months, and is a critical step is developing ToM.

Pretend play allows children to develop the skill of separating a representation from a

reality (Miller, 2006). Wellman & Liu (2004) showed an extended series of conceptual

insights in preschoolers as ToM develops. At this age, children are becoming aware that

others have different beliefs, and may have wants and likes different than their own.

A longitudinal study by Eggum et al. (2010) examined the development of

emotional understanding, ToM, and prosocial orientation in children over time by taking

measurements at 3.5, 4.5, and 6 years of age. Emotional understanding is the ability to

identify others’ emotions, a skill that was shown to develop over time. Prosocial

orientation is defined as voluntary behavior intended to benefit others. Examples

include: helping, sharing or cooperating without a source of direct motivation. As

emotional understanding and ToM develops across the preschool and school years, along

with language and reasoning, prosocial behavior was also shown to increase. Eggum et

al. found that at 4.5 years those with more developed ToM, as judged by false-belief

tasks, had higher levels of mother-reported prosocial behavior. A child’s mental

3 understanding of others appears to allow for a deeper understanding of other’s

challenges, fostering prosocial behavior.

Lalonde & Chandler (1995) showed that preschool children who performed better

on ToM tasks tended to play more cooperatively and engaged in longer play sessions than

preschool children with less developed ToM. Theory of Mind is additionally correlated

with language development. Children with increased mean length of utterance (MLU)

and higher vocabulary scores tend to do better in tests of ToM. An intact language

representation is necessary to understand and express abstract language and ideas, which

underlie ToM (Miller, 2006).

Another area that may impact the development of friendship is the pragmatic

consequence of using AAC while communicating with peers. AAC can either

supplement or replace spoken language, providing a way to communicate. However, this

may disrupt the typicality of communication. Peer responsiveness to communication

attempts is a critical component of language development. Many missed opportunities

for communication development have been observed in interactions between AAC users

and their communication partners. Eye contact and gaze, an important part of

communication and pragmatic development is often lacking (Reichle, Hidecker, Brady,

& Terry, 2003). AAC users tend to take on a more passive role in conversations. The

partner often asks a much higher ratio of closed-ended questions to open-ended

questions, resulting in the production of fewer items of information per conversational

turn by the individual using AAC. Communication is often limited to exchanging basic

wants and needs, and individuals using AAC are shown to rarely initiate interactions

(McConanchie & Pennington, 1997).

There are many forms of AAC ranging from no technology (e.g. white board,

paper and pencil) to high technology systems (e.g. iPad). Gestures, sign systems,

orthography, Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS), Pragmatic Organization

Dynamic Display (PODD), and speech generating devices (SGD) are among the most

4 widely used strategies (Reichle & Buekelman & Light, 2002). Research suggests that the

earlier an AAC system is put into place for a child, the greater the likelihood of

preventing developmental delays in communication. AAC provides an immediate

approach to communication, and it can also help children begin to develop prelinguistic

skills and expand vocabulary.

The acquisition of communication skills is a dynamic process influenced by both

the speaker and listener (Reichle & Beukelman & Light, 2002). However, interventions

are often solely aimed at the individual using an AAC system (Kent-Walsh & Rosa-Lugo,

2006). Communication breakdowns often seen in AAC are most commonly related to the

skills of the communication partner. When teachers, parents or peers fail to understand

the initial intent of the message, or ignore the attempt completely, maladaptive behaviors

by the child often serve as the first attempt at a repair strategy. Typically, these

maladaptive behaviors are more effective in gaining the partner’s attention, and as such

are reinforced (Brady & Halle, 2002). This cycle of maladaptive behaviors has

successfully been targeted in communication partner intervention by training skills such

as implementing a pause time to allow for a response by the child with ASD, and looking

rather than listening for a communication turn (Brady & Halle, 2002).

A number of studies have explored the effects of training teachers to improve

their roles as communication partners of children with ASD using AAC. The skills most

often targeted in teacher interventions are: extended pause time, responding to

communication attempts of the child, asking more open-ended questions, correctly

positioning the AAC system for the child, and modeling correct AAC use (Kent-Walsh &

McNaughton, 2005). Pennington et al. (1993) implemented the program “My Turn to

Speak,” (MTS) with teachers of children communicating with AAC. The teachers were

trained in the use of the strategies and at four months post-intervention the teachers

showed significant gains over the control group in quality of interactions with students

who use AAC. The teachers in the intervention group provided the children with more

5 opportunities for communication, increased their pause time, and increased their

responses to the child’s attempts to communicate. Teacher training has been shown to be

an effective way to improve the communicative interactions of children who use AAC

(Pennington, 1993); however, teacher training does not encompass the crucial aspect of

social development and formation of friendships.

A less researched area that is currently receiving more attention, involves the

development of programs focused on training peers. Peer-training programs have been

looked at in relation to training peers to be effective communication partners for a variety

of children with varying developmental disabilities, ASD, or who may use AAC. Using

peers, rather than adults, is suggested as the most effective strategy for increasing the

communicative interactions of children who use AAC, and has been shown to be

effective for those as young as preschool (DiSalvo & Oswald, 2002). Three main types

of peer interventions have been reported in the literature. Each type of intervention

varies in the degree that the peer takes on an instructional role, as well as the role of the

child with a disability in the training.

The most common peer-training program is target-focused instruction. It involves

teaching the child who uses AAC strategies for communication. The peer is included in

the intervention merely to serve as a communication partner and receives no direct

training. In peer-focused interventions, peers are taught to act as instructors and

facilitators of communication. Lastly, in dyad-focused interventions, both the child using

AAC and the peer communication partner are taught, together or separately, how to

support each other in communication. All three interventions, although minimally

researched, have shown positive gains in communication and peer relationships.

However, the dyad-focused interventions target the area of pragmatics within

communication, thus supporting the natural development of friendships and social

language (Fisher & Shogren, 2012). The responsibility to initiate or maintain a

conversation is shared by both communication partners, coinciding with a natural

6 communicative interaction. Peer-mediated interventions have been specifically targeted

for use with children with ASD, as peers can provide great models of expected behaviors

and patterns of communication development.

Today an increasingly larger number of children with ASD are being integrated

into general education classrooms. The number of children with ASD who use AAC is

also increasing, and peer training in AAC competence is progressively more critical to

the social and communicative development of the children who use AAC (King & Fahsl,

2012). Research has shown that the majority of interactions children using AAC have in

the classroom are with their paraeducator or teacher (Chung, Carter & Sisco, 2012).

Children who use AAC are more likely to communicate with these adults because they

are better able to meet the children’s communication needs (King & Fahsl, 2012). If

peers are trained and provided with the strategies to also successfully meet the complex

communication needs of children with ASD who use AAC, it would follow that the

social and language development of the children with ASD would also improve.

King & Fahsl (2012) provide specific guidelines for what should be included in

peer-mediated interventions that are geared towards younger children. They suggest that

peers first increase their knowledge of different types of communication. Playing

charades or watching cartoons that use non-verbal communication are sources of

exposure for young peers to start understanding multimodal communication. Peers then

should be taught explicit information regarding AAC systems, particularly those that their

peers are using. This can be accomplished by targeting game playing activities, like

“bingo” or “go fish”. Peers must also come to understand the barriers that

communicating with AAC can present. Role-playing and having communication limited

in some way can help in the peers’ developing insight into these communication barriers.

Finally, the intervention strategies for communicating with children using AAC need to

be taught. Strategies that King & Fahsl (2012) suggested include: giving the child using

7 AAC plenty of time to formulate their message, asking open-ended questions to

encourage discussion, and modeling use of the AAC device.

There have been a number of peer-training interventions reported in the literature

that have focused on school-aged children communicating with peers that have ASD and

who use AAC. Trottier, Kamp, & Mirenda (2011) conducted a peer-focused intervention

for peers communicating with children that have ASD who use speech generating devices

(SGD). The peers were trained in the basics of the SGD and how to navigate through the

device content. They were instructed on prompts they can use to help their peers with

ASD communicate while playing a game. Peers receiving the intervention were

instructed to wait before prompting, model use of the SGD, and to prompt the use of the

SGD if needed. A trainer was initially present during the play sessions in order to prompt

the peers when they should be prompting the child with ASD. As the training continued

the trainer no longer provided prompts to the peers, as they were expected to take on the

instructional role independently. The children using AAC demonstrated an increase in

communication acts made after peer prompting, suggesting that the peer-focused

intervention was successful in training school-aged peers to take on an instructional role,

and that children with ASD are responsive to prompting by peers. School-aged children

appear to be able to take on the role of a peer-mediator independently; however, there is

nothing that can be found in the literature to suggest a similar effect for children in

preschool.

As mentioned earlier, preschool children are in the process of developing Theory

of Mind (ToM), or the ability to consider another’s perspective. In order to

independently engage in the expected prosocial behaviors targeted in peer-training

programs a child must have a developed ToM to consider another’s differences and

perspective. Peer-training programs require processing of abstract language, engagement

in pretend play, and cooperation without direct motivation. These skills develop

8 differently over time in all children, but typically begin to appear during the preschool

years (Eggum et al., 2010).

Trembath et al. (2009) is one of the few studies to report effects of peer-focused

intervention of preschool children. Story scripts were used to inform the peer models

what was expected of them. They were taught how to model use of the AAC system and

how to implement peer-mediated teaching. The target principles taught to the peer

models were to “show, wait, and tell,” the child with ASD what to do. Teacher prompts,

not controlled for, were provided to peer models as needed. The children with ASD

increased their use of communicative behaviors during the intervention context of play,

and some children demonstrated a slight generalization to a non-intervention context of

snack time. The results suggest that preschool children can act as successful peermediators and increase the communicative behaviors of children with ASD who use

AAC. However, peer-mediators at this age appear to need consistent teacher prompts to

correctly implement the strategies. McGregor (2000) reported that spontaneous peer

modeling is only one component of an intervention program for preschool age children.

If an opportunity to model is present, but not acted on by a peer, the clinician or teacher

must prompt the trained peer to implement the strategy.

As inclusive preschool classrooms become more widespread continued research

into peer-training programs is necessary. Goldstein and English (1997) also reported

results that are supportive of peer training in preschool aged children. In this study peers

were trained to use a set of facilitative strategies, “stay, play, talk,” as well as to be more

aware of communicative attempts from their classmates with disabilities. The peers were

trained in these strategies and then paired with a classmate with a developmental

disability. Goldstein & English’s results show an increase in the number of interactions

between the peer-target child dyads in the classroom, and support the use of peer training

for improving the communicative interaction and social integration in inclusive

preschools.

9 An important factor that may influence the success of peer training is a function

of the expectations that the peers have of the children using AAC. Beck et al. (2002)

reported factors intrinsic to children that play an influential role in reported attitudes

towards children using AAC. Gender was a large contributor, with girls being more

accepting of children using AAC than boys. However, the most important predictor of

reported attitudes was prior familiarity with people with disabilities. This supports not

only inclusive preschool classrooms, but also early peer-intervention training. If the level

of familiarity of communication differences can be increased early on in the school years,

interactions throughout the school years and beyond may be positively influenced.

Although limited, a review of the literature supports the use of communication

partner training for increasing communication acts from children with ASD using AAC

(Trottier, 2011; Trembath, 2009; Goldstein & English, 1997). With teacher prompting,

the effectiveness of peer training has been demonstrated in children as young as

preschool age (Trembath, 2009). Despite the demonstrated effectiveness, the use of peer

training in preschools continues to be rare. One concern has been that implementation of

peer training may interfere in the academic learning of peers. However, research has

shown that inclusive classrooms and involvement in peer training programs do not

decrease the academic gains made by normally developing preschool children (Choi,

2007).

Few interventions focus on teaching the peer communication partner and the child

with ASD who uses AAC together, supporting the development of a natural social

relationship (Fisher & Shogren, 2012). Additionally, the peer-mediated intervention

programs that are typically chosen teach peers how to take on an instructional role. This

role may not support the development of natural peer relationships, that are often the

primary goal of peer training.

The present study aimed to provide preschool peers with instruction on ways to

engage with and support the complex communication needs of children with ASD who

10 use AAC. It aimed to teach peers about alternative forms of communication and provide

them with a set of strategies to better support their interactions with children with ASD.

It aimed to support the natural development of friendship, and thus peers were trained to

support, not instruct, the children with ASD. The study tested two hypotheses. Can

training increase preschool peers’ awareness of children with ASD during play, as

demonstrated by an overall increase in interactions, use of trained strategies, and

awareness of AAC use by the child with ASD? Do children with ASD increase

appropriate communicative behaviors when interacting with trained peers?

11 CHAPTER II

METHODS

Participants

Ten preschool children, 4 and 5 years old, participated in this study. Children

were enrolled in either the KidTalk I or KidTalk II afternoon preschool at the Wendell

Johnson Speech and Hearing Center. Both KidTalk I and KidTalk II are inclusive

classrooms. Each classroom has five typically developing children to serve as peer

models. In KidTalk I there are additional children that have been identified as having

speech and language impairments and have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP). In

KidTalk II there are additional children with speech and language impairments or Autism

Spectrum Disorders (ASD) that have an IEP. The current study involved four participant

groups.

Training Subject

The training subject (TS) was a boy with ASD in the KidTalk II classroom whose

age at the start of training was 4:2. During the training program, training peers were

taught strategies with TS as the target recipient. TS’s picture and name appeared in the

social narratives used in the training. TS communicated primarily with gestures, oneword verbal approximations, and through the Pragmatic Organization Dynamic Display

(PODD) system. PODD is a system that organizes aided symbol vocabulary to support

communication for functional purposes during daily activities. Each page of the PODD

is organized to provide vocabulary for a particular topic or situation. It should be noted

that the entire PODD book was not present during sessions, but single laminated pages

corresponding to each specific activity were appropriately positioned around the room.

Control Subject

The control subject (CS) was a boy with ASD in the KidTalk II classroom whose

age at the start of training was 5:4. CS served as a generalization subject for this training

study. He was not present during any of the peer training sessions, and strategies were

12 not taught to the training peers with him as the direct target. CS’s participation allowed

the researchers to observe the generalization of the trained strategies across children with

ASD. CS communicated primarily by verbal expression, although his verbal expressions

were characterized as echolalic or comments not always appropriate to the conversational

topic.

Training Peers

Four normally developing children that did not have any identified speech and

language impairment or ASD served as training peers. Two children were randomly

selected from both the KidTalk I and KidTalk II classrooms. These children participated

in the entire training study. The two participants from KidTalk I were not classmates of

the target or control subject, and had limited interaction with the subjects outside of the

study. Training peer 1 (TP1) was a male who at the start of the study was 5:3. Training

peer 2 (TP2) was a female who at the start of the study was 4:11. The two participants

from KidTalk II were classmates of the subjects, and had daily classroom instruction and

interaction alongside of them. Training peer 3 (TP3) was a male who at the start of the

study was 4:11. Training peer 4 (TP4) was a female who at the start of the study was 5:1.

KidTalk I and KidTalk II are located across the hall from each other. There is some

interaction between classrooms for certain activities and when on the playground, but for

the majority of the day the children are in their assigned classroom.

Control peers

Four normally developing children that did not have any identified speech and

language impairment or ASD served as control peers. Two children were randomly

selected from both the KidTalk I and KidTalk II classrooms. Control peer 1 (CP1) was a

male from KidTalk I who at the start of the study was 4:9, and control peer 2 (CP2) was a

female from KidTalk I who at the start of the study was 4:6. Control peer 3 (CP3) was a

male from KidTalk II who at the start of the study was 4:11, and control peer 4 (CP4)

was a female from KidTalk II who at the start of the study was 4:11. These children

13 received no training. The participation of these children allowed the researchers to

observe general developmental gains in the target behaviors over the 3-month

intervention period.

Consent

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Iowa

Institutional Review Board. To obtain consent of the participants’ parents, a letter of

interest was sent home by the classroom teacher for eligible children. Once families

expressed an interest in the study their contact information was shared with the

researchers to follow-up with the consent process. All consents were obtained in either

the KidTalk I or KidTalk II classrooms after parents had the opportunity to ask questions

about the study. Parents were informed that their child’s participation would not impact

academic instruction or services provided by the school.

Training Content

The training protocol was presented to the training peers via video modeling,

social narratives, and direct instruction with practice opportunities. At the first training

session trained peers listened to a researcher created social narrative entitled, “Some Kids

Use Picture Boards to Talk” (See Appendix A). The narrative used pictures of TS and of

the PODD.

The social narrative explained that different people talk in different ways and that

TS sometimes uses a picture board to tell people want he wants or what he likes. It also

explained that when TS uses a picture board the peers should try to look at the board so

they can see what TS is saying. Additionally, the social narrative explained that it might

help TS if they held the picture board up to him while playing to let him make choices.

The training peers then viewed a 1-minute video of two researchers modeling use of the

PODD during play (See Figure 2.1). After listening to the social narrative and watching

the video, the training peers were given an opportunity, in groups of two, to practice

using the picture boards with the researcher. Toys and associated PODD boards were

14 available. Each trained peer took a turn pretending not to talk and trying out

communication via the picture board.

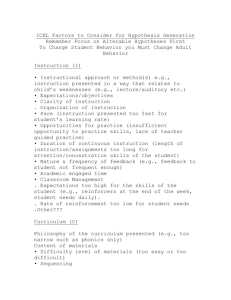

Figure 2.1 Screen shot from the video of researcher modeled PODD use

During the second training session, peers were trained on three behavioral

strategies to use when interacting with TS. First, training peers listened to a researchermade social narrative entitled, “It Can Be Fun When Everyone Plays Together” (See

Appendix B). The narrative included pictures of TS and other classmates playing

independently and then together. It explained that TS might be playing alone because he

needs help joining the group. The narrative encouraged the training peers to invite TS to

join the group. The training peers then watched three 30-second researcher-made videos

demonstrating each of the target strategies (e.g. show, wait, and tell.)

The first target strategy was to “show” TS what they are doing or something to

play with. For example, “I’m going to play with blocks, want to play?” while showing

TS a block. The video modeling the strategy included two researchers playing with a

15 farm set. Researcher 2 was playing alone when researcher 1 approached her and showed

her a toy animal while inviting her to play with the farm set. The training peers were

given the opportunity to practice this strategy immediately following the video. Each

training peer (TP) took a turn playing alone and the other TP approached him or her with

a toy and invited him or her to play. Each TP practiced and demonstrated the strategy a

minimum of 3 times.

The second strategy was to “wait” for TS to play or take a turn talking. In the

video modeling of this strategy, researcher 1 asked researcher 2 what she wanted to play

with. Researcher 1 then imposed a delay to allow researcher 2 to respond using the

PODD. Immediately after watching the video the training peers practiced using the

“wait” strategy. Each TP took a turn using the PODD, and the other TP asked him or her

questions while watching the PODD and waiting for an answer. Each TP practiced and

demonstrated the strategy a minimum of 3 times.

The third strategy was to “tell” TS what to do or how to do something. For

example, “TS, put the block on the top.” In the third video, researcher 1 tells researcher 2

to stack the block on the tower. After watching the video, each TP practiced and

demonstrated the tell strategy a minimum of 3 times. At the end of the training session

all three strategies were reviewed and the pair of two training peers worked together to

explain their understanding of each strategy to the researcher. The researcher

supplemented the peers’ understanding as needed.

Protocol

The training program lasted 12 weeks. Each session occurred during the normal

school day and ranged from 15-30 minutes in length. Sessions were conducted during

free play to ensure children did not miss any academic instruction or snack time.

Sessions took place in a large therapy room in the Wendell Johnson Speech and Hearing

Center. Children were taken out of class by the researcher and brought down the hall to

the therapy room. The room was set up to mimic the classroom environment with four

16 centers, each with a set of different toys. Each session was recorded using two video

cameras within the room. The two cameras ensured the entire room was being captured

on video.

A series of codes were used to classify the session types. Table 2.1 below

presents the codes given to each participant. Table 2.2 presents the codes given to the

participant groups, and Table 2.3 presents the codes given to each session type. Each

session received the following code of “date-who was involved-session type.” For

example “3-8-CP-baseline,” is the code given to the session that occurred on 3/8 that was

a baseline session involving all control peers. Each of the four participant groups had a

unique protocol. Table 2.4 outlines the sessions each peer attended throughout the study.

Table 2.1 Participant Codes

C1

C2

C3

C4

T1

T2

T3

T4

TS

CS

Control Peer # 1

Control Peer # 2

Control Peer # 3

Control Peer #4

Trained Peer #1

Trained Peer #2

Trained Peer #3

Trained Peer #4

Target Subject

Control Subject

17 Table 2.2 Participant Group Codes

CP

CP1

CP2

TP

TP1

TP2

All Control Peers

Control Peers Group 1

Control Peer #1 and Control Peer #2 (Students in KidTalk I)

Control Peers Group 2

Control Peer #3 and Control Peer #4

(Students in KidTalk II)

All Trained Peers

Trained Peer #1 and Trained Peer #2 (Students in KidTalk I)

Trained Peer #3 and Trained Peer #4

(Students in KidTalk II)

Table 2.3 Session Codes

Session Code

Training 1

Training 2

CP1

Session Type

Training 1

Training 2

Controlled Practice 1

CP2

Controlled Practice 2

AP

Advanced Practice

Final Training

Final Training

Final Test

Final Test

Baseline/Final

Baseline/Final

Session Description

PODD training

Strategy training

Clinician provided prompting to TP during

interactions with TS

Clinician provided prompting to TP during

interactions with TS

TP interacted with TS with no clinician

input

A sticker chart was introduced to TP. TPs

were given a final opportunity to practice

strategies.

TP interacted with TS. A sticker chart was

present, and stickers were awarded to peers

for strategy usage. The clinician prompted

strategy usage every 3 minutes.

Initial and final sessions between each

participant group.

18 Table 2.4 Outline of Protocol for Each Participant

Session Code 3-­‐8-­‐CP-­‐

baseline 3-­‐8-­‐TP-­‐

baseline 3-­‐12-­‐TP1TS Session Date 3/8/13 Ses. # 3/8/13 2 3/12/13 3 3-­‐12-­‐TP2TS 3/12/13 4 3-­‐13-­‐CP2TS 3/13/13 3-­‐15-­‐CP1TS 3/15/13 3-­‐26-­‐TP1CS 3/26/13 3-­‐26-­‐TP2CS 3/26/13 3-­‐27-­‐TP2-­‐

training1 3-­‐29-­‐CP1CS 3/27/13 4-­‐2-­‐CP2CS 4/2/13 4-­‐2-­‐TP1-­‐

training1 4-­‐3-­‐TP2-­‐

training2 4-­‐5-­‐TP1-­‐

training2 4-­‐9-­‐TP1TS-­‐

CP1 4-­‐9-­‐TP2TS-­‐

CP1 4-­‐16-­‐TP1TS-­‐

CP2 4-­‐16-­‐TP2TS-­‐

CP2 4-­‐26-­‐TP2TS-­‐

AP 4-­‐30-­‐TP1TS-­‐

AP 5-­‐1-­‐TP2-­‐

training 4/16/13 5-­‐3-­‐TP1-­‐

training 5-­‐7-­‐TP2TS-­‐

finaltest 5-­‐8-­‐CP1TS-­‐

finaltest 5-­‐10-­‐TP1TS-­‐

finaltest TS CS T1 T2 T3 T4 C1 C2 C3 C4 x x x x x x x x x x x x x x 5 TS and CP2 Baseline 6 TS and CP1 Baseline 7 CS and TP1 Baseline 8 CS and TP2 Baseline 9 TP2 Training #1 x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x 4/2/13 10 CS and CP1 Baseline 11 CS and CP2 Baseline 12 TP1 Training #1 x x 4/3/13 13 TP2 Training #2 x x 4/5/13 14 TP1 Training #2 x x 4/9/13 15 TS and TP1 Controlled Prac. #1 16 TS and TP2 Controlled Prac. #1 x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x 5/1/13 17 TS and TP1 Controlled Prac. #2 18 TS and TP2 Controlled Prac. #2 19 TS and TP2 Advanced Practice 20 TS and KidTalk I TP Advanced Practice 21 TP2 Final Training x x 5/3/13 22 TP1 Final Training x x 5/7/13 23 TS and TP2 Final Test 24 TS and CP1 Final Test 25 TS and TP1 Final Test x x x x x x x x x 3/29/13 4/9/13 4/16/13 4/26/13 4/30/13 5/8/13 5/10/13 1 Session Description Control Peer Baseline Session Training Peer Baseline Session TS and TP1 Baseline TS and TP2 Baseline 19 Table 2.4. Continued 5-­‐14-­‐CP2TS-­‐

finaltest 5-­‐17-­‐CP-­‐

finalbaseline 5-­‐17-­‐TP-­‐

finalbaseline 5-­‐21-­‐TP1CS-­‐

final 5-­‐28-­‐CP1CS-­‐

final 5-­‐28-­‐CP2CS-­‐

final 5-­‐28-­‐TP2CS-­‐

final 5/14/13 26 5/17/13 27 5/17/13 28 5/21/13 29 5/28/13 30 5/28/13 31 5/28/13 32 TS and CP2 Final Test Control Peer Final Session Training Peer Final Session CS and TP1 Final Session CS and CP1 Final Session CS and CP2 Final Session CS and TP2 Final Session x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x x Training Peers

The training peers participated in a total of 12 sessions. One session occurred

each week with the exception of sessions #2 and #3 which both occurred during the

second week of the study. No sessions were conducted over the preschool’s Spring

Break.

In session #1, baseline data for all 4 training peers interacting were collected over

a period of 20 minutes. A researcher was present during the session, but sat to the side to

minimize any impact on the interaction. In the remainder of the sessions, with the

exception of session #10, KidTalk I and KidTalk II training peers attended sessions

separately.

In session #2, baseline data were recorded of the training peers interacting with

TS. In session #3, baseline data were recorded of training peers interacting with CS.

Each session lasted approximately 15 minutes. A researcher was present during the

session, but sat to the side to minimize any impact on interaction.

In session #4, training peers received strategy training. During the session the

peers were introduced to the PODD system that TS uses in the classroom to

communicate. Children watched a social narrative, “Some Kids Use Picture Boards to

20 Talk,” and viewed a video of two researchers modeling PODD use within the classroom.

After watching the social narrative and the video, each child was given approximately 10

minutes to practice using the PODD to communicate.

In session #5, training peers received additional strategy training. During the

session the children were introduced to the three target strategies, “show, wait, and tell,”

to use with TS. The children viewed the social narrative, “It Can Be Fun When Everyone

Plays Together,” and viewed three short clips of the researchers modeling each of the

three strategies. After each video the children were given time to practice each new

strategy.

In session #6 and #7, training peers took part in controlled practice of the

strategies with TS. A researcher was present in this session to model strategy use and

prompt use of the strategies by the training peers. If an opportunity to use strategies was

presented, but not identified and acted on by the training peers, the researcher cued

strategy use by the training peers. The session lasted for approximately 20 minutes.

In session #8, training peers participated in advanced practice of the strategies

with TS. A researcher was present during the session, but sat to the side to minimize any

impact on interaction. No prompting to use the trained strategies was provided. The

session lasted for approximately 15 minutes.

In session #9, feedback was provided to the training peers regarding their

performance in session #8. All strategies were reviewed by re-watching the videos.

Peers were given additional opportunities to practice each strategy. Additionally, during

session #9 a new reinforcement system was introduced to the training peers in the form of

a sticker chart. Each training peer was given a picture with nine empty boxes drawn on

it. Each time a strategy was demonstrated by a training peer, a sticker was immediately

placed into the box. The session lasted for approximately 20 minutes. The session served

as a final reminder of the strategies before the final sessions in which they interacted with

TS and CS.

21 Session #10 involved the final observation of the training peers interacting with

TS. The sticker chart reinforcement system was used during this session. Additionally,

the researcher provided the following prompt every 3 minutes, “Remember to use your

strategies to try to earn stickers,” to remind the training peers of the session’s goal. The

session lasted approximately 15 minutes.

In session #11, a final observation of all 4 training peers interacting was obtained

over a period of 20 minutes. A researcher was present during this session, but sat to the

side to minimize any impact on interaction.

Session #12 involved the final observation of the training peers interacting with

the control subject, CS. This session provided data to determine whether the use of the

trained target strategies generalized to interactions with other children with ASD. The

sticker chart reinforcement system was also used during this session. Additionally, the

researcher provided the following prompt every 3 minutes, “Remember to use your

strategies to try to earn stickers,” to remind the training peers of the session’s goal. The

session lasted approximately 15 minutes.

Control Peers

The control peers received no training and participated in a total of 6 sessions.

Each session lasted approximately 15-20 minutes. In all sessions a researcher was