Women`s Employment, Unpaid Work and Economic Wellbeing

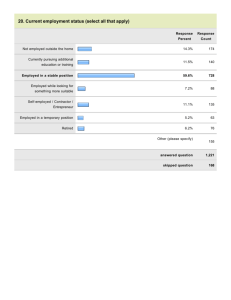

advertisement