Has monetary policy ultimately become too loose?

advertisement

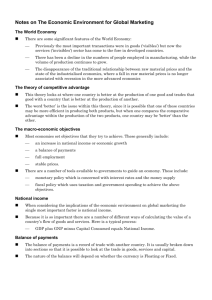

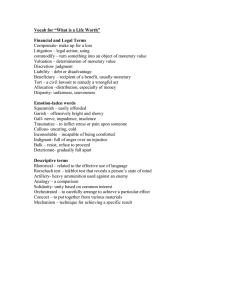

Global Strategic Outlook Has monetary policy ultimately become too loose? 6 UPDATE II/2016 GLOBAL STRATEGIC OUTLOOK Globally, central bank rates remain stubbornly close to all-time lows averaging 0.5% in advanced economies and 2.2% including emerging markets. 7 Thanks to the rise in oil prices inflation rates have started to increase to a global average of AUTHOR: STEFAN HOFRICHTER In December 2015, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) finally raised interest rates for the first time since 2008 when rates were reduced to virtually 0%. However, other major central banks, notably the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the Swedish Riksbank, lowered rates further. Indeed, the BoJ joins the ECB, the Swedish Riksbank, the Danish National Bank and the Swiss National Bank in testing the waters with negative central bank rates. The ECB, along with the central banks of Japan and Sweden, has also indicated a further expansion of its quantitative easing policy: all three banks have planned higher liquidity injections into their respective markets. Emerging markets are not immune to these problems and several emerging market economies have also cut interest rates including India, Indonesia, Poland and Hungary. While communications from the Fed (e.g. via quarterly updates of its famous “dot charts”) suggest further rate hikes are likely this year, market expectations point towards only one more rate hike and that too with a probability of 50%. Likewise, expectations of the first Bank of England (BoE) rate hike have been pushed back further into the future. The markets are not ruling out a rate cut, as the next likely step by the “Old Lady on Threadneedle Street” either. So nine years on since the Great Financial Crisis, and global monetary easing continues with no end in sight. 8 UPDATE II/2016 GLOBAL STRATEGIC OUTLOOK process of policy normalisation. This is particularly true for the Fed, which has been most explicit in pointing to the impact of international developments on its monetary policy and interest rate decisions. We have to ask ourselves: · Is further easing actually required? · What are the major costs associated with the current stance in monetary policy? · Has monetary policy become too loose? Inflation: less bleak than at the beginning of the year Inflation data, too, look less bleak than at the beginning of the year. Thanks to the rise in oil prices – the key driver for headline inflation in the near term – inflation rates have increased to a global average of 1.8%. Core inflation, while marginally down since January of this year, is still hovering at around 2% globally. This is around its highest level since the beginning of the decade, despite GDP levels that are lower than they were pre-crisis. Following years of under investment in the developed world, notably in research and development (R&D), productivity growth has come down. Consequently, potential growth rates are lower than they were before the Global Financial Crisis; output gaps are narrowing (or have already closed). Core inflation rates, meanwhile, are edging up, despite disappointing economic activity compared to pre-2007. Even though long-term inflation expectations measured by surveys – as opposed to markets – have edged lower during the last two years, in both the US as well as in Europe, they remain at around the target levels set by their central banks. This is important because if prices were expected to fall, consumers and companies would be inclined to postpone spending, thereby There is no doubt that global economic growth continues to be lacklustre. Data from the developed world showed growth edging down towards the end of 2015 and during early 2016 following turbulence in emerging markets last summer. Our own forecasting tools suggest economic growth is, nevertheless, likely to be at around potential in the developed world (i.e. slightly below 2% in the US and slightly above 1% in the euro area in real terms). We have also received the first tentative positive economic data out of emerging markets, including China. Even more importantly, the massive capital outflows from emerging markets, especially during the summer of 2015, which were at the root of the sharp rise in volatility in capital markets, have lost momentum and in some cases probably stopped. Central banks in the West have repeatedly highlighted potential spill over effects from emerging markets (read China) to their respective economies. So any improvement in economic data in emerging markets may actually relieve some of the pressure to further ease or to postpone the 9 01 INCRE ASING INCIDENCE OF FINANCIAL CRISES AND ASSET BUBBLES SINCE THE END OF BRET TON-WOODS Share of countries in crisis since 1900 Percentage points S&P 500 60% 10,000 50% 1,000 40% 30% 100 20% 10 10% 0% 1 1900 1910 % of DM in crisis 1920 1930 % of EM in crisis 1940 1950 1960 int. monetary system regime change 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 S&P 500 Sources: Allianz Global Investors; Datastream; Schularick, M. und Taylor, A. M. (2009): “Credit Booms Gone Bust: Monetary Policy, Leverage Cycles and Financial Crisis, 1870–2008”; L.Laeven and F.Valencia:, IMF WP/08/224 “Systemic Banking Crisis Database”; definition of crisis years according to Schularick/Taylor (1900-2010) and Laeven/Valencia (1970-2008); own estimates for years since 2008 DM: G7, Australia, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Sweden; EM: Argentina, BRICS, Chile, Hong Kong, Hungary, Indonesia, Israel, Korea, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, Poland, Singapore, Thailand, Turkey 10 Year UPDATE II/2016 GLOBAL STRATEGIC OUTLOOK driving down demand in the economy. In sum, economic activity and inflation dynamics, while far from splendid, do not necessarily suggest that more monetary stimulus is warranted. We think there is scope to start the process of policy normalisation. · Firstly, if the yield curve flattens substantially as a consequence of bond purchases by central banks, the profitability of the banking sector will suffer and hamper it ability to lend. Indeed, the net interest margins of US and European banks have declined steadily over the past two years. Moreover, recent stimulus measures implemented by the ECB, BoJ and Riksbank have not weakened the Euro, Yen or the Krona respectively. On the contrary, all three currencies have since appreciated. Markets seem to have lost faith in the magical powers of central banks and their ability to stimulate growth especially as the potential effect of the banks’ continued policy easing has been offset by the ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies of other central banks. · Secondly, negative central bank deposit rates, currently in place in countries representing around one quarter of the world’s GDP, are particularly detrimental to a banking system largely dependent on retail deposits. For political reasons, it is not possible to pass on negative deposit rates on reserves held at the central bank to retail customers by cutting interest rates on deposits into negative territory. Negative deposit rates therefore simply drive up costs for banks and reduce their profitability. As the ECB’s most recent lending survey shows, negative interest rates will become a serious concern for the banking system in the euro area if the current rate environment persists for much longer. There are other reasons to argue that the monetary policy being pursued by central banks in the developed world may have become too loose. Most importantly, changes in monetary policy will have limited effect on economic growth if weaker growth compared to the pre-crisis period is due to weak aggregate supply rather than low aggregate demand. Of course, effective monetary policy measures can still help stimulate investment activity, but these alone will not guarantee a rise in potential growth rates. A strong monetary policy must be accompanied by structural reforms designed to enhance productivity as well as labour growth via rising labour participation or immigration. Ultra-easy monetary policy may also feed new excessive credit booms. As capital mobility has risen substantially since the 1990s – according to the Chinn-Ito index, global capital account openness has increased significantly since the 1980s – loose monetary policy has been exported to the rest of the world. The pursuit of easy monetary policy by major central banks may actually have contributed to strong credit growth outside their jurisdiction. Indeed, post-2008 and following the massive response of the Fed, ECB and BoE after the financial crisis, we have observed a sharp rise in non-financial credit in countries hardly, if at all, affected by the crisis in the emerging and developed world. Chart 01 Financial Instability: risks on the horizon? In addition, an ultra-easy monetary policy pursued for too long may actually increase financial instability either by weakening the banking sector or by facilitating the formation of credit bubbles. Leverage in the non-financial sector has reached all-time highs and now stands at more than 230% of world GDP with the private sector in emerging markets, especially in China, The banking sector can suffer from the consequences of an ultra-easy monetary policy in two ways: 11 Leverage in the non-financial sector has reached all-time highs and now stands at more than 230% of world GDP. being the main culprit. We estimate that non-financial private debt in China has risen to more than two times GDP. This number compares to 1.6 times GDP for the average of advanced economies just before the Global Financial Crisis. It is not only the level of debt that is worrisome, but also the pace of its build-up. The credit gap, defined as the deviation of private sector leverage from trend, has reached double-digit levels in several economies, notably China, Brazil, Turkey, Hong Kong and Singapore. to fend off any major disruptions in the financial system. However, it does suggest that credit growth has been too strong in large parts of the world, notably emerging markets. This is weighing significantly on the outlook for trend growth going forward as banks may have to increase provisioning. Chart 02 Could these developments be linked to the ‘accommodative’ monetary policy stance adopted by central banks after the Global Financial Crisis? Clearly, it is impossible to track money flows and establish watertight causal relationships between monetary policies being pursued in the developed world and credit growth elsewhere. What we do know, though, is that over the last 30 years or so, major central banks’ policy rates have generally been below what is considered “neutral”, as derived from trend nominal GDP growth. Furthermore, US monetary conditions, as measured by the Chicago Fed Monetary Conditions Indicator, have been quite favourable. And yet, the last 30 years have been characterized not only by solid economic activity around the world – real global GDP growth has averaged 3.5% since the mid 1980s – but also by ever more frequent cycles of credit booms and busts. Historically, we have seen that all major crises since the break-up of the Bretton-Woods system were preceded by wide credit gaps. The Great Financial Crisis of 2007/08; the Asian crisis of 1997/98; the Mexican (and Latin American) Tequila crisis of 1994/95 and the financial crisis in the Nordic region during the 1990s all shared the same marker. In the US too, debt levels in the non-financial corporate sector have increased substantially since the beginning of this decade – up almost 100% according to bottom-up data for listed companies! This is not to say that a new financial crash is around the corner. China, in particular, with currency reserves in excess of USD3 trillion, has the means 12 UPDATE II/2016 GLOBAL STRATEGIC OUTLOOK 13 02 CENTR AL BANK R ATE S VS “NEUTR AL” LE VEL (= R ATE S REL ATIVE TREND NOMINAL GDP) Percentage points 8 6 4 2 0 –2 –4 Year 1985 1980 USA UK 1990 EMU 1995 2000 JAP Sources: Allianz Global Investors Economics & Strategy, Datastream, Thomson Reuters; as of:27.04.2016. 14 2005 2010 2015 UPDATE II/2016 GLOBAL STRATEGIC OUTLOOK What are the implications for investors today? Stefan Hofrichter has been Head of Global Economics and Strategy Group at Allianz Global Investors since 2011. His research activity focuses on the areas of global and European economic development, asset allocation and equity strategy. He joined the company in 1996 as a European equity portfolio manager. Since 1998, he has been working in the field of macroresearch. Between 2004 and 2010, he also managed European and global balanced funds, multi-asset-absolute-return funds and multi-manager-alpha-porting funds. Stefan Hofrichter became a member of the AllianzGI Global Policy Council, which determines the company’s medium-term capital market assessments. Since 2013, he has also been a member of the newly created investment committee for tactical asset allocation, which is responsible for the investment strategy of the multi-asset mandates managed in Europe. From 2010 to 2012, he chaired the Asset Allocation Committee for balanced funds managed out of Frankfurt. Stefan Hofrichter holds a degree in Economics from the University of Konstanz (1995) and in Business Administration from the University of Applied Sciences of the Deutsche Bundesbank, Hachenburg. He became a CFA Charterholder in 2000. Easy monetary policy has generally provided a positive backdrop for economic growth and risky assets, notably right after the financial crisis. However, too much easing for too long also comes at a cost. We should therefore take any further potential stimulus measures with a pinch of salt. It will take more than just a monetary stimulus to raise asset prices. In the long run, reasonable valuations (for European equities as well as emerging market assets); a regular income stream – an argument in favour of dividend strategies and selective spread products and a solid and stable growth outlook are more important. In addition, risk management has to become an integral part of superior asset management solutions in order to address the rising probability of higher market volatility ahead. 15