Comparison of Presence and Extent of Coronary Narrowing in Patients With Left

Bundle Branch Block Without Diabetes Mellitus to Patients With and Without

Left Bundle Branch Block But With Diabetes Mellitus

Ozcan Ozeke, MD*, Dursun Aras, MD, Bulent Deveci, MD, Mehmet Fatih Ozlu, MD,

Ozgul Malcok Gurel, MD, Aytun Canga, MD, Veli Kaya, MD, Tumer Erdem Guler, MD,

Ali Yildiz, MD, Kumral Ergun, MD, Mehmet Timur Selcuk, MD, Serkan Topaloglu, MD,

Orhan Maden, MD, and Omac Tufekcioglu, MD

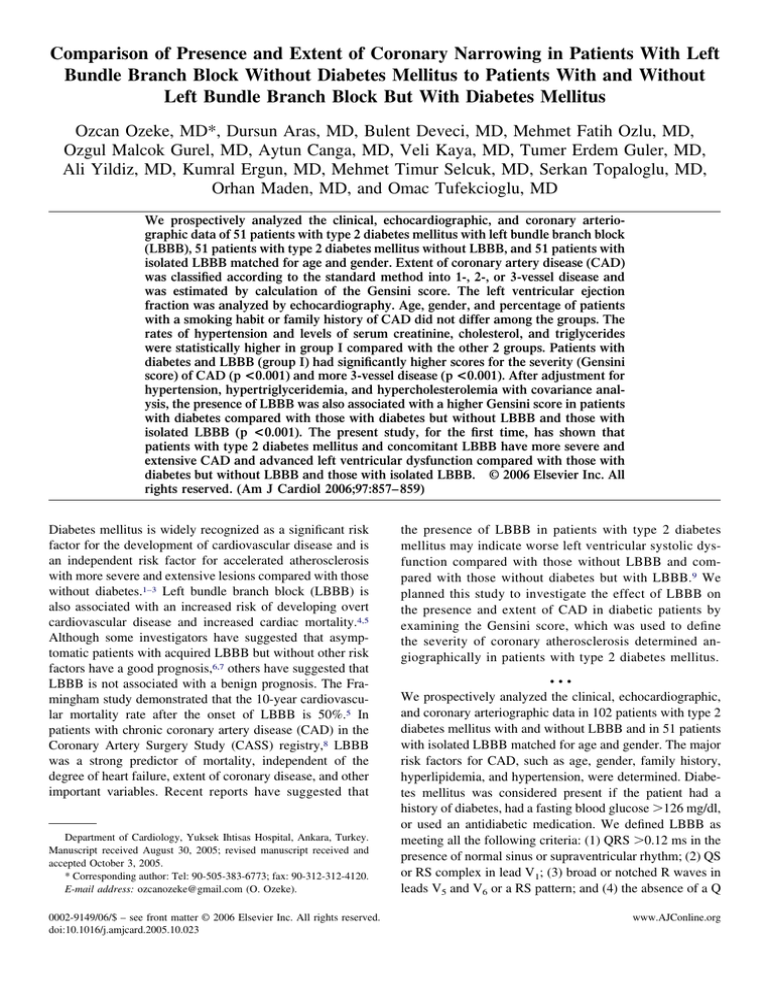

We prospectively analyzed the clinical, echocardiographic, and coronary arteriographic data of 51 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with left bundle branch block

(LBBB), 51 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus without LBBB, and 51 patients with

isolated LBBB matched for age and gender. Extent of coronary artery disease (CAD)

was classified according to the standard method into 1-, 2-, or 3-vessel disease and

was estimated by calculation of the Gensini score. The left ventricular ejection

fraction was analyzed by echocardiography. Age, gender, and percentage of patients

with a smoking habit or family history of CAD did not differ among the groups. The

rates of hypertension and levels of serum creatinine, cholesterol, and triglycerides

were statistically higher in group I compared with the other 2 groups. Patients with

diabetes and LBBB (group I) had significantly higher scores for the severity (Gensini

score) of CAD (p <0.001) and more 3-vessel disease (p <0.001). After adjustment for

hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypercholesterolemia with covariance analysis, the presence of LBBB was also associated with a higher Gensini score in patients

with diabetes compared with those with diabetes but without LBBB and those with

isolated LBBB (p <0.001). The present study, for the first time, has shown that

patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and concomitant LBBB have more severe and

extensive CAD and advanced left ventricular dysfunction compared with those with

diabetes but without LBBB and those with isolated LBBB. © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All

rights reserved. (Am J Cardiol 2006;97:857– 859)

Diabetes mellitus is widely recognized as a significant risk

factor for the development of cardiovascular disease and is

an independent risk factor for accelerated atherosclerosis

with more severe and extensive lesions compared with those

without diabetes.1–3 Left bundle branch block (LBBB) is

also associated with an increased risk of developing overt

cardiovascular disease and increased cardiac mortality.4,5

Although some investigators have suggested that asymptomatic patients with acquired LBBB but without other risk

factors have a good prognosis,6,7 others have suggested that

LBBB is not associated with a benign prognosis. The Framingham study demonstrated that the 10-year cardiovascular mortality rate after the onset of LBBB is 50%.5 In

patients with chronic coronary artery disease (CAD) in the

Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) registry,8 LBBB

was a strong predictor of mortality, independent of the

degree of heart failure, extent of coronary disease, and other

important variables. Recent reports have suggested that

Department of Cardiology, Yuksek Ihtisas Hospital, Ankara, Turkey.

Manuscript received August 30, 2005; revised manuscript received and

accepted October 3, 2005.

* Corresponding author: Tel: 90-505-383-6773; fax: 90-312-312-4120.

E-mail address: ozcanozeke@gmail.com (O. Ozeke).

0002-9149/06/$ – see front matter © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.023

the presence of LBBB in patients with type 2 diabetes

mellitus may indicate worse left ventricular systolic dysfunction compared with those without LBBB and compared with those without diabetes but with LBBB.9 We

planned this study to investigate the effect of LBBB on

the presence and extent of CAD in diabetic patients by

examining the Gensini score, which was used to define

the severity of coronary atherosclerosis determined angiographically in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

•••

We prospectively analyzed the clinical, echocardiographic,

and coronary arteriographic data in 102 patients with type 2

diabetes mellitus with and without LBBB and in 51 patients

with isolated LBBB matched for age and gender. The major

risk factors for CAD, such as age, gender, family history,

hyperlipidemia, and hypertension, were determined. Diabetes mellitus was considered present if the patient had a

history of diabetes, had a fasting blood glucose ⬎126 mg/dl,

or used an antidiabetic medication. We defined LBBB as

meeting all the following criteria: (1) QRS ⬎0.12 ms in the

presence of normal sinus or supraventricular rhythm; (2) QS

or RS complex in lead V1; (3) broad or notched R waves in

leads V5 and V6 or a RS pattern; and (4) the absence of a Q

www.AJConline.org

858

The American Journal of Cardiology (www.AJConline.org)

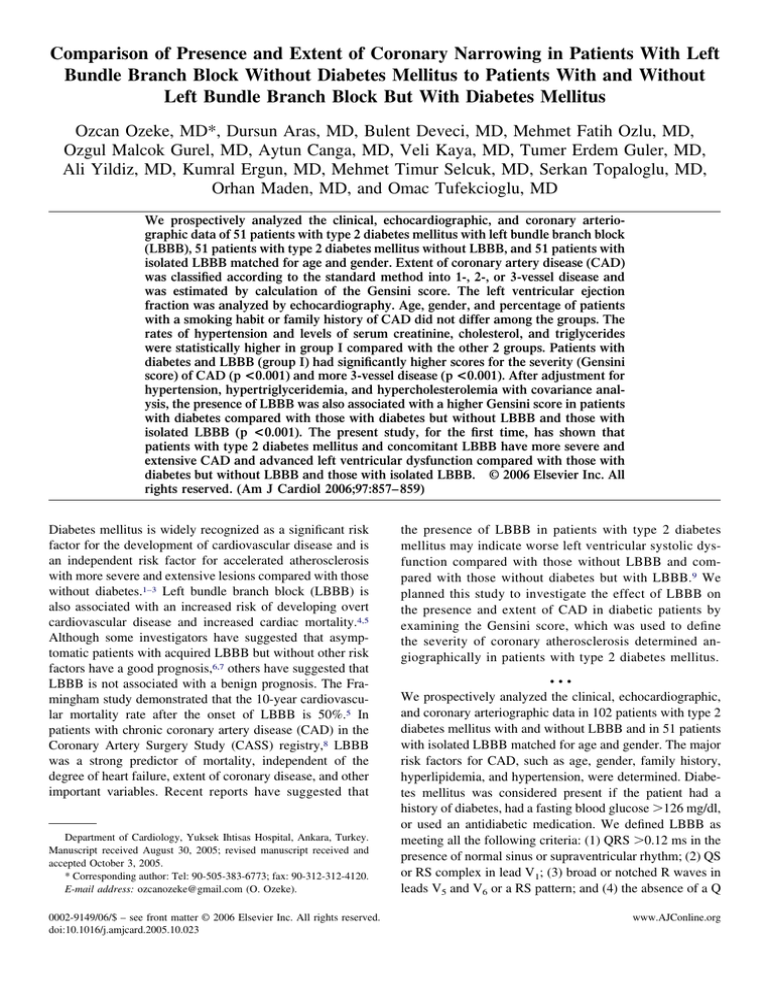

Table 1

Clinical, laboratory, echocardiographic, and angiographic data of

study population

Variable

DM With

LBBB

(n ⫽ 51)

DM Without

LBBB

(n ⫽ 51)

Isolated

LBBB

(n ⫽ 51)

p Value

Age (yrs)

Women (%)

Hypertension (%)

Family history for

CAD (%)

Smoking (%)

Triglycerides

(mg/dl)

Cholesterol

(mg/dl)

HDL-C (mg/dl)

LDL-C (mg/dl)

Creatinine (mg/dl)

BMI (kg/m2)

LVEF (%)

Presence of CAD

Single-LAD (%)

Single-LCx (%)

Single-RCA (%)

2-Vessel (%)

3-Vessel (%)

Gensini score

64 ⫾ 9

31 (61%)

39 (77%)

12 (23%)

64 ⫾ 9

28 (55%)

31 (61%)

9 (18%)

63 ⫾ 11

29 (57%)

27 (45%)

10 (20%)

NS

NS

⬍0.001

NS

7 (14%)

188 ⫾ 97

7 (14%)

168 ⫾ 83

6 (12%)

135 ⫾ 77

NS

⬍0.001

197 ⫾ 49

188 ⫾ 43

173 ⫾ 34

⬍0.001

41 ⫾ 11

118 ⫾ 44

1.1 ⫾ 0.5

28 ⫾ 4

32 ⫾ 11

35 (69%)

7 (14%)

2 (4%)

1 (2%)

9 (18%)

16 (31%)

50 ⫾ 58

43 ⫾ 11

112 ⫾ 37

1.0 ⫾ 0.4

28 ⫾ 6

52 ⫾ 10

28 (55%)

6 (12%)

3 (6%)

2 (4%)

8 (16%)

9 (18%)

28 ⫾ 43

44 ⫾ 12

99 ⫾ 29

0.9 ⫾ 0.3

27 ⫾ 3

45 ⫾ 13

23 (45%)

6 (12%)

2 (4%)

2 (4%)

5 (12%)

6 (12%)

14 ⫾ 26

NS

NS

0.037

NS

⬍0.001

0.05

NS

NS

NS

NS

0.04

⬍0.001

BMI ⫽ body mass index; LCx ⫽ circumflex artery; DM ⫽ diabetes

mellitus; HDL-C ⫽ high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LAD ⫽ left

anterior descending artery; LDL-C ⫽ low-density lipoprotein cholesterol;

LVEF ⫽ left ventricular ejection fraction; RCA ⫽ right coronary artery.

wave in leads V5, V6, and I.10 Laboratory data for the serum

levels of total, high-density lipoprotein, and low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, and creatinine were

recorded for all patients. The left ventricle ejection fraction

was analyzed by echocardiography. To estimate the presence and extent of CAD, the coronary angiograms of all

patients were analyzed. Patients with no angiographic disease or irregularities in any of the epicardial coronary arteries were considered to have normal coronary arteries on

angiography. The severity of CAD was determined visually

by a single experienced observer, and CAD was defined as

a 50% reduction in the internal diameter of the left anterior

descending artery or right or circumflex coronary artery or

their primary branches. The extension of CAD was classified according to the standard method into 1-, 2-, or 3-vessel

disease and was estimated by calculation of the Gensini score.

The Gensini score was computed by assigning a severity score

to each coronary stenosis according to the degree of luminal

narrowing and its geographic importance.11

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows

(release 11.5, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used for

statistical analysis. The categorical variables are expressed

as a percentage and were analyzed by chi-square statistics.

The continuous variables are expressed as means and were

analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance, with Tukey post

hoc testing when appropriate. A 2-tailed p value of ⱕ0.05

was considered significant.

The data of 51 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with

LBBB (group I, mean age 67 ⫾ 8 years, 65% women) were

compared with the data of 51 patients with diabetes but

without LBBB (group II, mean age 68 ⫾ 10 years, 61%

women) and with the data of 51 patients without diabetes

but with LBBB (group III, mean age 65 ⫾ 10 years, 61%

women). The serum triglyceride and total cholesterol levels

in group I (diabetes mellitus and LBBB) were significantly

higher than the levels in groups II and III (p ⬍0.001);

however, no significant difference was found in the highdensity lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

levels among the 3 groups (p ⫽ NS). Hypertension was

more prevalent in group I than in group II or III. The body

mass index was higher in the diabetic patients (groups I

and II), but had no statistical importance (Table 1). The

serum creatinine level in group I (diabetes mellitus and

LBBB) was significantly higher than in group II or III

(p ⬍0.037).

The mean left ventricular ejection fraction in group I was

significantly lower than in groups II and III (p ⫽ 0.01).

Normal coronary arteries were more prevalent in the isolated LBBB group (55% in group III vs 45% in group II and

31% in group I). The prevalence and localization of 1-vessel

disease were not statistically different among the 3 groups

(Table 1). The prevalence of multivessel disease (2- or

3-vessel disease) was 49% in group I, 33% in group II, and

23% in group III. The Gensini angiographic score was

higher in group I than in groups II and III (p ⬍0.001).

Because statistically significant differences were found for

hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypercholesterolemia among the 3 groups, univariate analysis of variance

was performed, which revealed continued statistical significance for the Gensini score (p ⬍0.001).

•••

Patients with diabetes have a considerable risk of cardiovascular disease, and up to 80% of deaths within this group

of patients are from cardiovascular disease.12 Recent reports

have suggested that the presence of LBBB in patients with

type 2 diabetes mellitus may indicate worse left ventricular

systolic dysfunction compared with those without LBBB.9

This study, for the first time, has demonstrated that the

presence of complete LBBB in diabetic patients is unequivocally associated with more extensive CAD, with higher

prognostic risk scores.

1. Eschwege E, Simon D, Balkau B. The growing burden of diabetes

mellitus in world population. Int Diabetes Fed Bull 1997;42:14 –19.

2. Raman M, Nesto RW. Heart disease in diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol

Metab Clin North Am 1996;25:425– 438.

3. Shehadeh A, Regan TJ. Cardiac consequences of diabetes mellitus.

Clin Cardiol 1995;18:301–305.

4. Fahy GJ, Pinski SL, Miller DP, McCabe N, Pye C, Walsh MJ, Robinson K. Natural history of isolated bundle branch block. Am J Cardiol

1996;77:1185–1190.

Arrhythmias and Conduction Disturbances/LBBB in Diabetes Mellitus

5. Schneider JF, Thomas HE Jr, Sorlie P, Kreger BE, McNamara PM,

Kannel WB. Comparative features of newly acquired left and right

bundle branch block in the general population: the Framingham Study.

Am J Cardiol 1981;47:931–940.

6. Smith RF, Jackson DH, Harthorne JW, Sanders CA. Acquired bundle

branch block in a healthy population. Am Heart J 1970;80:746 –751.

7. Beach TB, Gracey JG, Peter RH, Grunenwald PW. Benign left bundlebranch block. Ann Intern Med 1969;70:269 –276.

8. Freedman RA, Alderman EL, Sheffield LT, Saporito M, Fisher LD.

Bundle branch block in patients with chronic coronary artery disease:

angiographic correlates and prognostic significance. J Am Coll Cardiol

1987;10:73– 80.

9. Guzman E, Singh N, Khan IA, Niarchos AP, Verghese C, Saponieri C,

Singh HK, Gowda RM, Vasavada BC, Cohen RA. Left bundle branch

859

block in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a sign of advanced cardiovascular

involvement. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2004;9:362–365.

10. Willems JL, Robles de Medina EO, Bernard R, Coumel P, Fisch C,

Krikler D, Mazur NA, Meijler FL, Mogensen L, Moret P, for the

World Health Organizational/International Society and Federation for

Cardiology Task Force Ad Hoc. Criteria for intraventricular conduction disturbances and pre-excitation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;5:1261–

1275.

11. Gensini GG. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the

severity of coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 1983;51:606 – 607.

12. Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality

from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in

nondiabetic subjects with and without myocardial infarction. N Engl

J Med 1998;339:229 –234.