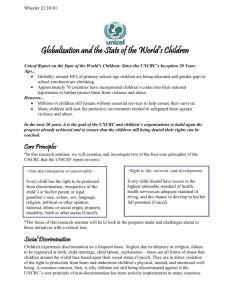

Opportunities and challenges in promoting policy

advertisement