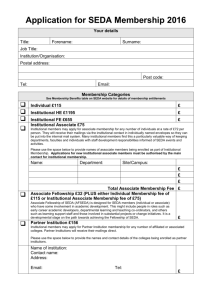

Document

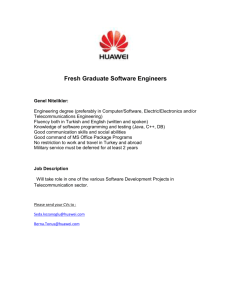

advertisement