Tech Giants and Civic Power

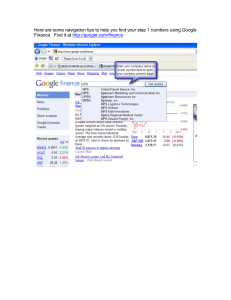

advertisement