On The Mobile The Effects Of Mobile Telephones On

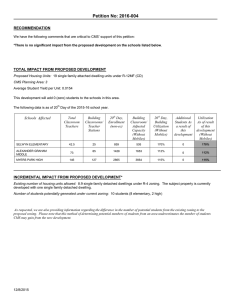

advertisement