Class meetings

for safe and caring

schools

By: Gene Gauthier

assisted by Charlotte Bragg and

Vicki Mather

Class meetings

for safe and caring

schools

By: Gene Gauthier

assisted by Charlotte Bragg and

Vicki Mather

Developed under agreement with the Minister of Education,

province of Alberta, Canada.

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities, 11010 142

Street NW, Edmonton AB T5N 2R1.

© 1999 by The Alberta Teachers’ Association

Published 1999

Revised © 2006 by The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and

Communities

All rights reserved.

Printed in Canada

Any reproduction in whole or in part without prior written consent of

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities is prohibited.

ISBN 1-897324-14-6

This booklet was authored by Gene Gauthier

and assisted by Charlotte Bragg and Vicki Mather.

Class Meetings for Safe and

Caring Schools

Holding class meetings1 can be an effective way to decrease

school discipline problems, thereby promoting a safe and caring

environment. This democratic problem-solving approach

serves to enhance responsible behaviour. This booklet discusses

the philosophical basis of holding class meetings and provides

instruction on class meetings in your classroom. Teachers will

need to adapt the strategies and examples provided to make them

suitable for the age group they are teaching. Class meetings have

been used successfully with students from primary grades through

to high school.

The concept of class meetings is developed by Frank Meder (1982).

1

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

1

Purpose of class meetings

The purpose or aim of class meetings is for the teacher and students

to collaboratively assist each other to solve social and curricular

problems in an atmosphere of mutual respect and dignity.

The approach of class meetings is to work on the first three or four

incidents (minor conflicts) of misbehaviour before they become

major, full-scale discipline problems.

This method is a democratic problem-solving approach, in which

students are given the autonomy to become self-disciplined,

responsible individuals. Through the process of encouragement

and the application of logical consequences, class meetings develop

self-esteem, self-confidence and feelings of worth within each

student. The main objective is to foster responsible behaviour

2

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

Adlerian concepts and principles

The philosophy behind the concept of class meetings is based

on the psychological principles of Alfred Alder (1870–1937). It

is therefore helpful to be familiar with a few basic principles of

Adlerian psychology as outlined below.

Humans are social beings

In Adlerian psychology, humans are seen as inherently social beings;

human problems are therefore regarded as social problems that

require the cooperation of others to solve. Thus, the more one

cooperates with others, the healthier one becomes psychologically.

The aim of class meetings is to train children early in life to

effectively solve social problems through collaboration with their

peers.

Purposive behaviour

Since humans are social beings, all behaviour is directed toward

social acceptance; that is, children need to feel accepted, to feel

significant, to feel a sense of belonging. Thus, behaviour is

purposive; it is directed toward securing a sense of belonging.

Class meetings give children the opportunity to participate and

achieve a sense of belonging. Participation in class meetings can

show children that attention and significance can be achieved

through useful, constructive means, rather than through mistaken

attempts to attain significance through useless, negative means

(misbehaviour).

Encouragement

Children who misbehave are “discouraged” or “without heart”;

that is, they have not learned how to gain significance in useful

ways. Through negative reinforcement, they have mistakenly

learned to become significant through useless behaviour, by

seeking undue attention, power or revenge, or by giving up and

assuming inadequacy (feeling they can’t become significant at all).

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

3

Class meetings reduce this misbehaviour and serve to encourage or

enhance self-esteem, allowing children to gain a sense of belonging

through constructive behaviour.

Holism

Adlerian psychology has a holistic emphasis that maintains that

the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Thus, the study of a

human being should not be compartmentalized. To understand a

person, one must study how that person interacts with his or her

total environment, and with other people. Thus, in a therapeutic

setting, a family-systems approach is taken, whereby the counselor

works with the whole family to improve relationships.

Because the classroom is viewed as a large family, class meetings

serve to improve relationships between and among peers.

4

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

Frank Meder’s Class Meeting

Model

Class meeting components

The best time to introduce this program is the first week of the

school year. The classroom teacher can introduce the concepts in

the order outlined below. The components are taught and practised

before the first class meeting is held.

Day One—Formation of a circle

The circle formation is essential in creating a democratic

atmosphere and promoting good communication skills. The circle

symbolizes and promotes a sense of equality among classmates. It

allows everyone to see everyone else’s facial expressions and body

language.

Teach kids how to get from rows into a circle—“Two Q’s, quickly

and quietly!” Don’t let 35 students rush at once. Structure is

important. Teach

in chunks.

When teaching the circle formation, prompt children to suggest

ways to get their desks out of the classroom structure and into the

circle. In this way, students are already developing problem-solving

techniques and learning that the solutions are student-directed, not

teacher-directed.

Begin with one row at a time while others watch. Proceed to the

next row and the next, and so on. The idea is to move the desks to

the periphery of the classroom, placing the chairs in front of the

desks. Students sit quietly in their chairs while the next row moves.

The teacher puts his/her chair in place, then calls students one at a

time to form a circle. The teacher sits in the circle with the students.

If the chairs are connected to the desks, then move each student

and his or her desk one at a time as described above.

Once the children are in a circle, have them notice their spot in

relation to something stationary in the room. They should also

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

5

notice who is seated to their left, right and across from them so they

will be able to move to the same spot for subsequent meetings.

The rest of this session is spent having students practise getting in

and out of the circle in a quick and quiet manner.

Hint: Teachers may develop a seating plan for many reasons. It is

easier if students move to the same spot every meeting. This avoids

children fighting about who sits beside whom. (For example,

“Yesterday we were friends. Today, I don’t want to sit beside . . .”)

It is better to have children sitting in chairs or desks rather than

sitting on the floor, as it is easier to establish one’s private space.

Hint: Use a stopwatch—students love to keep track of their own

“personal best” time getting into and out of the circle quickly and

quietly. Skilled students take between 15–30 seconds.

Day Two—Compliments

Class meetings should always begin on a positive note. After the

students have formed their circle, Day Two is spent teaching pupils

about encouragement. Self-esteem is enhanced by helping students

recognize each other for their positive contributions, allowing them

to gain acceptance.

Instruct students on how to give and receive compliments. Why

is this necessary? Adults are often poor at giving and receiving

compliments. We give them for material things, training children to

compliment for material things rather than acceptable behaviour. (An

example of a good compliment is, “You did a great job tidying up

the books today! They were stacked neatly on the shelf which will

make it easy for us to find them later.”)

Teach pupils that compliments are something you say to someone,

or a group of people, to tell them what they did that you appreciate.

Compliments are statements of encouragement about something

someone did for you, or with you, or something nice to help

another person.

Compliments should emphasize the behaviour or the deed, not the

doer. Promote the idea that compliments should emphasize what

a person has done that is acceptable, not just what the person

possesses or who they are.

6

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

Compliment format

Compliments may be given to one or two students by saying: “I’d

like to compliment

, and

for

.”

If more than two people are to be complimented, say: “I’d like to

compliment all those who

.”

(This can be used to save time.)

“Thank you”

Train students to say “thank you” after receiving a compliment, to

let the other person know that the compliment was heard and that

they were listening. This promotes respect.

Have students practise giving compliments. Go around the circle

calling each student by name. Students can then either give a

compliment to a peer or pass. (This allows the student to think of a

compliment without being put on the spot.)

The second time around, the teacher calls on the students who

passed. If students put up their hand after the second time around,

they will have to wait till the next class meeting. (Only go around

twice to save time for the rest of the meeting.)

Pitfalls to avoid

Compliment refusals

For the student who refuses to give a compliment, have other

students give a compliment that they would give if they were

[Billy].

For example, “Would anyone like to give a compliment if you were

[Billy], and we’ll see if he likes any of the suggestions?” Then the

teacher says, “Billy do any of these sound exciting to you?” “No,

not really,” replies Billy, “But the one about walking home doesn’t

sound bad.” Well, do you want to use that one?” responds the

teacher.

Hint: Notice in the example that the teacher didn’t back the child

into a corner. Instead, the teacher allowed other students to work

on him. If children are forced to give compliments, they give poor

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

7

compliments—“plastic fuzzies,” fake or phony compliments or end

up engaging in a power struggle.

Material compliments

Compliments are not given for material things, such as clothes.

Give compliments for realistic things, deeds, and for things people

have done, behaviour.

Talk to the students about not “buying” compliments. For example,

students shouldn’t go home and say, “Mommy, take me out

shopping so I can get a compliment tomorrow.”

The “best friend” compliment

When a student says, “I’d like to compliment

for being

my best friend,” politely discourage this kind of complimenting

by letting pupils know that this can be hurtful to others. Help the

children understand that if we say that someone is best, that means

that someone else is less than best. This is discouraging.

Should best friend compliments occur in a meeting, ask the student

giving the compliment, “Would you give a compliment to

for what he/she did that shows you she/he is a good friend or is a

friendly person?”

Multiple compliments

Each person may only give one compliment per meeting. If

students indicate that they have more than one compliment to give,

say, “Give us your best one today, and save the next one for the

next meeting.”

“Back-stabbing” compliments

Negative compliments need to be discouraged. An example of

a poor compliment would be, “I’d like to compliment Fred on

playing a great soccer game and not bugging me.”

“Don, can you rephrase that sentence with only the compliment?”

By getting the class to decide, the power is taken from the

individual student.

The “uncomplimented”

The teacher can compliment the whole class for genuine classroom

improvements and give each student a compliment in the circle.

8

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

He/she can give the student, who doesn’t get many circle

compliments, some throughout the day.

Here are some suggestions to inspire creative compliments in your

classroom. Tell the students to consider the following:

• Prepare two or three compliments to give—in case your first

choice was given by someone else!

• Give a unique compliment to a person you haven’t

complimented before or for a behaviour you haven’t seen

before.

• Imagine what it would be like if you never received a

compliment. Keep in mind that you want to give compliments

to different people.

Hint: Students enjoy keeping an “encouragement booklet.” They

can write examples during the week and select one prior to the

class meeting.

Hint for Starting Out: For the first 5 days of the compliments

segment, name sticks can be used as a written assignment. The

teacher can add some compliments to the list of students who did

receive only a few compliments. All students will have an equal

amount of compliments. The compliments could be displayed on

a bulletin board with each student’s picture and/or sent home

with the newsletter. At the beginning of the year, try printing the

students’ names on popsicle sticks and putting them in a colorful

can. Have each student draw the name of someone to compliment.

This is helpful when students are just starting out and may not be

sure who to compliment.

Be careful not to force students to give compliments, as described

above. Compliments should come from the heart.

Hint: Compliment time can be the most encouraging part of the

day for some students. Teachers also find that the compliments can

be the most fruitful part of the class meeting as they can see the

resulting increase in the self-esteem level of the children.

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

9

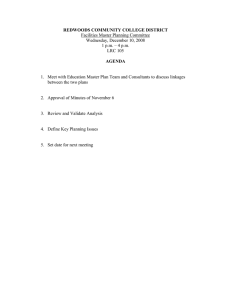

Day Three—Agenda

As with most adult meetings, class meetings are never held without

an agenda. If children are going to be making decisions during

class meetings, what are they going to be making decisions on? The

agenda comprises social problem-solving matters and curricular

concerns, such as planning a field trip, planning a class party or

planning other academic projects that the teacher and students

work on together.

Discuss how the agenda will be made up. The agenda can be a

loose-leaf folder or notebook placed on a counter top or in any

other convenient and visible location.

Students are responsible for adding items to the class meeting

agenda on their own time. If they are too young, the teacher can

assist them.

Hint: Students are taught to try to solve problems on their own

before placing items on the agenda. However, if the problem

persists, they should place the item on the agenda (so as not to

promote tattling). Students should, however, be encouraged to

report behaviour that is harmful to another person, like bullying

and instigator. The instigator is a student who steps in to tease

the bully, then backs away to watch the result. “The person who

is accused is identified...” The accused person should never be

identified, even in the classroom. The self-esteem at all times is

paramount.

It is important that students understand that they are not to

add items to the agenda during class time while the teacher is

instructing. They are responsible for doing this on their own time.

(Therefore, the agenda item must be important to that individual.)

Discuss with the children when to add items to the agenda.

Some good times are when they are leaving for morning recess,

lunchtime, afternoon recess or on their way home. Discourage

students from writing in the agenda immediately after coming in

from recess, as a cooling off period can be important.

Hint: Allow a few minutes before the listed times above.

10

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

Teach and consistently reinforce the importance of confidentiality.

What is discussed in class meetings should not be shared with

others outside the classroom. Names of the accused should not be

written on the agenda which could be read by others who are not

members of the class. The person who is accused can be identified

during the class meeting if the student who wrote the problem on

the agenda wishes to pursue a solution.

Hint: If students are old enough to understand, teach them about

the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act while

discussing the importance of confidentiality. Remind students often

to focus on solving the problem behaviour and not the person.

How to use the agenda

For students who can write

1. Write your name on the agenda.

2. In parenthesis, write down the problem.

NAME:

Dan

Jan

Teacher

PROBLEM:

(A student in our class tripped me during soccer.)

(Someone stole my pen. My pen is missing.)

(Book shelves are untidy.)

For students who can’t write

There are several ways this can be handled, however, the teacher

usually writes the students’ names and their concerns in the

agenda.

Hint: Teachers say that the process of recording items on the

agenda can be as important (or even more important) as discussing

the items during the class meeting. For example, when a student

complains to a teacher about a peer, the teacher listens and

respectfully says, “That sounds like something you may want to

place on the agenda!” This takes the teacher “off the hook” from

dealing with the issue at that moment. This teaches independence

and encourages children to solve their own problems without adult

intervention. However, teachers should be sensitive to reports that

may involve bullying. If a bullying issue is not successfully dealt

with through classroom meetings other measures must be taken.

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

11

Refer to the bullying booklets in this series for more information on

the topic of bullying.

Problems are often solved before they are placed on the agenda.

For example, “If you don’t give back that ball, it’s going on the

agenda!” is a veiled threat. The student could be told to say, “You

are being disrespectful”. If the incident is not solved, then he/she

will know that it will be an agenda item. Items may also be placed

on the agenda but solved before the class meeting. For example,

Janet places the issue of missing pencils on the agenda. Ron sees

it and says, “Oh Jan, here are your pencils. I found them in my

desk. I didn’t realize I had them.” The problem is solved before the

meeting and can be skipped over when it comes up on the agenda.

Hint: Meetings should not go beyond 30 minutes at the upperelementary level.

If you don’t cover all the items on the agenda, continue from where

you left off at the next meeting. If not held daily, meetings should

be held at least three times a week. Otherwise, the agenda items can

become backlogged. If problems aren’t solved within a reasonable

time frame, students become discouraged and class meetings

lose their value. Problems revert to getting the teacher to resolve

everything. This leads to stress, burnout . . . and unsafe, uncaring

schools.

How can you rationalize taking time for class

meetings?

Add up the time you currently take trying to control discipline. You

will find more time is spent on discipline than for class meetings.

Without the meetings, teachers can become stressed by attempting

to solve the students’ problems, rather than training them how to

resolve their own issues.

Days Four and Five—Natural and logical

consequences

Students are trained to differentiate consequences from

punishment. Punishment is unacceptable in a democratic classroom

or in a safe and caring school.

12

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

Consequences are an alternative to autocratic punishment. The

aim of consequences is to assist children to become responsible

for their own behaviour and thus, self-disciplined individuals.

Consequences should help children learn more appropriate ways to

behave.

Natural consequences

Introduce the concept of natural consequences on Day Four with

the following role play:

Imagine that this morning you got up to go to school and you

were hungry, so you made some Tosties. You poured milk on

your cereal and began to gobble it down, when suddenly, you

looked at the clock, only to discover that it was time to rush

off to school. No one was left at home and you hurried off to

school. On the way there, you realized that you forgot to finish

your cereal or put the milk away.

What is the natural consequence that will happen before you get

home?

Hint: Do not accept answers with human involvement.

Discuss possible natural consequences for these situations. What’s

the natural consequence of the following situations?

• If mom or dad doesn’t put gas in the car

• If the dishes are not washed for a week

• If the shingles blow off the house and you don’t fix them

• If you don’t brush your teeth

• If you don’t take a bath

• If you go outside in the winter without a coat

Hint: Help children to realize that natural consequences are

arranged by nature and not by people.

Logical consequences

Logical consequences occur when people arrange the consequence.

Explain to the students that, because we are social beings, social

problems arise. Nature cannot solve these issues, so we need to

learn how to solve these problems ourselves.

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

13

Explain to the students that most of the problems placed on the

agenda will be solved through logical consequences. The class will

come up with the consequences together, after they have learned a

few guidelines.

The “Four Rs” of logical consequences

Before a consequence can be logical it must be

1. Related: Explain that this means goes with, has something to do

with, belongs to, is like. For example, you forgot to set the table

when it was your turn so your father asks you to clear the table

after dinner.

2. Reasonable: Explain that this means not too easy or simple, not

too severe or difficult, something just right. For example, Marnie

broke Yuet’s pencil so Marnie was asked to use money from

her allowance to buy Yuet a new pencil. Many students do not

receive an allowance and some students have pencils provided

to them.

Another example might be, “You broke someone else’s toy/game,

a reasonable result would be to replace it with your own money.

If you do not have any money, you will have to work at home or

school to earn some money to pay for it.

#3. For example, be replaced with: If you call someone a nasty

name, you are being disrepectful to that person. The consequences

will be that you will lose a good friend, or many friends because

other students will notice how you treat others. Continue with:

“Remind students...”

Teacher Note: The student’s anonymity is paramount.

3. Respectful: If a consequence is going to be respectful, it must

not hurt anybody’s feelings or make him or her feel bad. For

example, Braeden called Alf a nasty name. We wouldn’t suggest

that Alf call Braeden a nasty name as a consequence because

that would be disrespectful. Instead, we might ask Braeden if

he could think of two genuine compliments and tell them to

Alf. Remind the class that the purpose of class meetings is to

help one another solve problems. We’re not out to get others,

to punish, hurt or make others feel bad about themselves, but to

14

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

help them learn from their misbehaviour. Everyone should be

left with his or her dignity intact.

4. Responsible: Explain that the person responsible for the

problem is held accountable for the consequence, not someone

else. #4. Explain to the students that we are responsible for our

own behaviour and accountable for the consequences of it. We

always have choices.

A consequence must fit all “Four Rs” to be a consequence;

otherwise it will likely be a punishment.

Class meetings are designed to be helpful, if a decision is not

helpful, then one of the “Four Rs” is not being followed and the

decision could be punishing. Punishment causes or encourages

people to get even or be revengeful. It results in unsafe and uncaring

schools.

Hint: If the “Four Rs” are listed on a poster or bulletin board the

students will be able to refer to them during class meetings and will

be reminded of them throughout the day. The “Four Rs” of logical

consequences are on a magnet and are available from the ATA’s

SACS Project.

The following examples may be used to teach students the

difference between logical consequences and punishment.

Instructions

K–3 can continue using circle time to discuss incidents as they arise

or

from the list below.

1. Divide the class into groups of three or four. Have the groups

choose roles: leader, secretary/reporter, timer and so on.

2. Present each group with one or two of the following problems

and have them brainstorm several possible solutions for each.

• Name-calling at morning recess.

• Kicking people during a soccer game.

• Trouble getting into line after lunch.

• Spitting on benches during gym.

• Switching seats on the bus.

• Wandering around the room during science class.

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

15

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Wasting time during library period.

Improper use of the restroom.

Not doing exercises during Phys. Ed.

Swearing at the lunch table.

Tardiness after lunch.

Not turning in homework.

Stealing pencils.

Laughing at another student who is showing negative or

painful behaviour

• Not allowing certain students to join in games at recess.

3. After 15–20 minutes, have each group secretary report their

possible solutions to each problem.

4. With the class as a whole, review which answers violate the

“Four Rs” criteria and which could be retained as a possible

logical consequence to be implemented by a class.

Hint: Remember, every item on the agenda doesn’t have to have

a consequence. Several agenda items may be dropped when they

come up because they are no longer important to the person who

placed them on the agenda or the problem may have been resolved.

(Isn’t it wonderful that the problems can be solved without the

teacher’s immediate intervention?)

Sometimes a decision cannot be agreed upon, so the situation is

merely discussed. For example, if a kickball was kicked up on the

roof the situation may be discussed without a consequence being

applied. (The natural consequence—that is, no ball to play with—

may be enough especially if such a situation seldom happens.) The

pupils may have reached a consensus that nothing will happen

this time until it gets put on the agenda again. For example...(the

natural consequence of the ball being kicked up on the roof...)”. The

consequence is that all students have to go without a ball because

of the action of one or more students. If a person had kicked hisown

ball on the roof, this would be a just action.

Solutions vs. consequences

Sometimes it is hard to tell if something is a solution or a

consequence; sometimes they may be a little of both. The solution

may be that nothing will be done about what happened this time.

16

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

But, the class will discuss a remedy to prevent the problem from

occurring again. For example, Bertha put a behaviour on the

agenda that involved James throwing her papers down on the floor.

James admitted to the behaviour. The teacher asked James what

he thought should happen. James said, “I don’t know, let the class

make some suggestions.” Some class suggestions were, “I think

he should apologize to Bertha,” “Write an apology,” “I think that

from now on, he shouldn’t let go until Bertha takes the papers from

him” and “I think we should move him to the back of the row, so

he won’t be able to throw anyone’s papers but his own.” (The latter

was the class’s decision.)

Often a discussion about a concern will bring about positive

change, without a consequence.

Example should be anonymous. Moving the student to the back of

the row is punishment. Write an apology is a respectable way to

handle it.

Video presentation

Teachers have found the “Class Meeting Video with Frank Meder”

and his class to be helpful in giving students a visual model of an

actual class meeting. Originally intended to train teachers, students

also benefit from the video. Show this video at the end of your

class meeting training week as a review and to show students two

sample meetings in action. See the “For More Info...” section for

information on how to order the video.

The following are the class meeting procedures outlined in the

video.

Class meeting procedures

1. The student who placed the item on the agenda defines the

incident.

2. Ask other students if they have any information about this

incident. No names are to be given. “Is that accurate?” Obtain

clarification. Classmates may ask questions or give input to

achieve clarification.

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

17

3. Omit #3 and #4. Ask the accused what should happen, give a

logical consequence. (This is a face-saving device; it also gives the

accused empowerment in solving the problem.)

4. Class vote: How many agree with

? If the majority agree,

then proceed to Number 8 below. If the majority disagree, then

proceed as follows.

5. No names will be used. Add: Review the four R’s of logical

consequences. Other suggestions: The class brainstorms three

other logical consequences, of which one will be selected as the

most helpful for the student named.

6. The teacher reads each consequence to the class to make sure

everyone understands what they are to vote on. The vote is

then taken by a show of hands. Students vote for only one

suggestion. Advise students to select the consequence that they

consider most helpful and not the most hurtful. Discourage

popularity votes.

7. The teacher declares the class decision. The accused is/are given

a limited choice, for example, “John, do you want to sit out

this afternoon’s recess or tomorrow morning’s?” The concept of

limited choice is to have the offender involved in the decisionmaking process, and also owning the responsibility. The result

is listed on a classroom chart to be referred to when the incident

arises again. The teacher deals with the misbahving student on

a one-to-one basis later and not in front of the class. Continue

with: The misbehaving student is given...” Replace the word

“problem” with incident.

8. Discuss helpful hints or tips. These suggestions help students

avoid the incident if it occurs again.

9. Next agenda item.

18

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

Conclusion

Be risk-takers—hold class meetings. Both you and your students

will greatly benefit from them. Your class meetings may not go

smoothly at first. But hang in there. Keep plugging. It won’t work if

you don’t try. Good luck!

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

19

For more info . . .

Bibliography

Allan, J., and J. Nairne. 1993. Class Discussions for Teachers and

Counsellors in Elementary Schools. 2d ed. Toronto: Ontario

Institute for Studies in Education.

Bubbico, M., F. Meder and J. Platt. “General Guidelines for

Meetings.” Unpublished handout. (see writer)

Dreikurs, R., B. Grunwald and F. Pepper. 1982. Maintaining Sanity

in the Classroom: Classroom Management Techniques. New York:

Harper & Row.

Krenz, D., and D. MacDougall. 1984. 25 Classroom Activities to

Change the World Through Encouragement: A Manual for Teachers

Counsellors and Principals. Edmonton: K. & M. Enterprises.

Meder, F. J. 1982. “Why Class Meetings?” Individual Psychology 38,

no. 2: 173–82.

Meder, F. J. “Class Meeting Video with Frank Meder.”

Nelsen, J. 1982. Positive Discipline. Fair Oaks, Calif.: Adlerian

Counselling Center.

Nelsen, J., L. Lott and S. H. Glenn. 1993. Positive Discipline in the

Classroom: How to Effectively Use Class Meetings and Other Positive

Discipline Strategies. Rocklin, Calif.: Prima Publishing.

Nelsen, J., 1996. et al. Positive Discipline: A Teacher’s A–Z Guide.

Rocklin, Calif.: Prima Publishing.

To order Frank Meder’s video on Classroom Meetings, please call

1-916-797-1100. The video costs US $50.00 (plus shipping and

handling). Schools can leave a message with the school name,

address and a purchase order number. The video will be shipped

and billed to the school.

For more information on class meetings, to order a copy of a

handout with general guidelines or to book a workshop on class

meetings, contact Gene Gauthier at St. Matthew School, 8735 132

Avenue, Edmonton AB T5E 0X7; phone (780) 473-6575 or fax

(780) 478-6031.

20

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

Websites

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

www.sacsc.ca

Alberta Education

//ednet.edc.gov.ab.ca/safeschools/content.html

Tri-faculty Research

(The Faculties of Education from the Universities of Lethbridge,

Calgary and Alberta):

www.education.ualberta.ca/educ/research/tri-fac/tri-fac.html

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

21

The Society for Safe and Caring

Schools and Communities

Resources

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities’ resources and materials

are available through Alberta Learning’s Resources Centre (LRC), 12360 142 St.

NW, Edmonton, Alberta, T5L 4X9. Tel: 427-5775 in Edmonton. Elsewhere in Alberta

call 310-0000 and ask for the LRC or fax (780) 422-9750. To place Internet orders,

visit www.lrc.learning.gov.ab.ca *These materials are eligible for the Learning

Resources Credit Allocation (25% discount). Contact the LRC for details. The

Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities has four program areas and

an inventory of promotional items:

I. SUPPORTING A SAFE AND CARING SCHOOL

This program area helps build a SACS culture. It includes information about SACS,

an assessment tool to aid in planning and quick, easy-to-read booklets that review

current research on SACS topics and successful programs.

□ Safe and Caring Schools in Alberta Presentation:

Includes Video, overheads and brochures. LRC # 455297

□ The SACSC: An Overview (K–12) (Pkg of 30)

Overview of SACSC programming. (2001, 4 pp.) LRC # 445298

$25.00 ea

$15.00 ea

□ Attributes of a Safe and Caring School (K–12) (Pkg of 30)

A brochure for elementary, junior and senior high schools, describing the

$15.00 ea

characteristics of a safe and caring school. (1999) LRC # 445313

□ The SACSC: Elementary Booklet Series (16 booklets) (K–6)

(see LRC website) LRC # 445610

$50.00 ea

□ The SACSC: Secondary Booklet Series (15 booklets) (7–12)

(see LRC website) LRC # 445628

$50.00 ea

□ Preschool Bullying: What You Can Do About It—A Guide for Parents and

Caregivers (1–6)

Advice on what parents can do if their child is being bullied or is bullying others

(2000, 24 pp.) LRC # 445347 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Bullying: What You Can Do About It—A Guide for Primary Level Students

(K–3) Contains stories and exercises to help children deal with bullies and to stop

bullying others (1999, 28 pp.) LRC # 445397 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Bullying: What You Can Do About It—A Guide for Parents and Teachers of

Primary Level Students

Tips to help teachers and parents identify and respond to children who are

involved in bullying (2000, 12 pp.) LRC # 445454 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Bullying: What You Can Do About It—A Guide for Upper-Elementary

Students and Their Parents

Directed at students who are the victims, witnesses or perpetrators of bullying,

and their parents (2000, 16 pp.) LRC # 445321 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE

22

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

□ Bullying in Schools: What You Can Do About It—A Teacher’s Guide (1–6)

Describes strategies that teachers can follow to stop bullying in schools (1997)

LRC # 445339 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Beyond Bullying: A Booklet for Junior High Students (7–9)

Explains what students should do if they are being bullied or if they see someone

else being bullied (2000) LRC #445470 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00ea

□ Beyond Bullying: What You Can Do To Help—A Handbook for Parents and

Teachers of Junior High Students (7–9)

Defines bullying behaviours and suggests strategies that parents and teachers

can follow to deal with it (1999, 16 pp.) LRC #445488 $4.00 ea for 10+ $5.00 ea

□ Bullying is Everybody’s Problem: Do You Have the Courage to Stop It?

(Pkg of 30) (7–12) A brochure for senior high students, defines bullying and

provides advice on how to respond to it (1999) LRC # 445305

$15.00/pkg

□ Bullying and Harassment: Everybody’s Problem—A Senior High Staff and

Parent Resource (10–12)

Provides advice for parents and teachers of high school students on how to deal

with bullying (2000, 12 pp.) LRC # 445496 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools (K–12)

Explains how regular class meetings can help teachers and students work out

conflicts before they become major problems (1998, 20 pp) LRC # 445587

$4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Expecting Respect: The Peer Education Project—A School-Based Learning

Model (K–12)

Provides an overview of Expecting Respect, a project that trains junior and senior

high students to make classroom presentations on establishing healthy social

relationships (1999, 16 pp.) LRC # 445462 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Safe and Caring Schools: Havens for the Mind (K–12)

Reviews the role of SACS in healthy brain development and learning

LRC # 445503 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Media Violence: The Children Are Watching—A Guide for Parents and

Teachers (K-12)

Contains tips for parents and teachers in countering the effects on children of

media violence (1999, 12 pp.) LRC # 445511 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Peer Support and Student Leadership Programs (K-12)

Describes effective peer support programming for various grade levels.

(2000, 30 pp.) LRC # 445503 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Niska News (K–12)

A collection of articles about SACS reprinted from The ATA News (1999, 36 pp.)

LRC # 445529 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

□ Principals’ Best (K–12)

Describes activities and strategies that various schools in the province have

undertaken to create a safe and caring environment for students (1999, 16 pp.)

LRC # 445545 $4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00 ea

PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

23

□ Volunteer Mentorship Programs: (K–12)

Describes a number of successful programs in which adult volunteers were

assigned to serve as mentors to school-aged children (2000, 28 pp.) # 445579

$4.00 ea for 10+

$5.00ea

□ Volunteer Mentorship Program: (K–12)

A video portrays programs in which adults from the community work with children

to help them develop various skills (1999, 9 ½ min.) LRC # 445602

$ 7.00 ea

□ Volunteer Mentorship Program: A Practical Handbook (includes 3.5” disk)

(K–12) Explains how to set up programs in which adults serve as mentors to

school-aged children (1999, 44 pp. plus a computer disk containing sample

documents used in the program) LRC # 445595

$10.00 ea

II. TOWARD A SAFE AND CARING CURRICULUM—

RESOURCES FOR INTEGRATION

These resources are recommended and approved by Alberta Learning. They

integrate violence prevention into all subjects K–6 and are divided into five topics:

(approximately 85 pp.)

1. Building a Safe and Caring Classroom/Living Respectfully

2. Developing Self-Esteem

3. Respecting Diversity and Preventing Prejudice

4. Managing Anger and Dealing with Bullying and Harassment

5. Working It Out Together/Resolving Conflicts Peacefully

Student resource sheets are available in French. To order, check (F).

Kindergarten

Grade 1

Grade 2

Grade 3

Grade 4

Grade 5

Grade 6

□ # 445446

□ # 445371

□ # 445389

□ # 445404

□ # 445412

□ # 445420

□ # 445438

F□

F□

F□

F□

F□

F□

F□

(Out of Province $69.00)

(Out of Province $69.00)

(Out of Province $69.00)

(Out of Province $69.00)

(Out of Province $69.00)

(Out of Province $69.00)

(Out of Province $69.00)

$49.00

$49.00

$49.00

$49.00

$49.00

$49.00

$49.00

□ Anti-Bullying Curriculum Materials: Social Studies Grades 10, 11, 12

Developed by Project Ploughshares Calgary, this booklet contains a series of

exercises that teachers can use to incorporate the topic of bullying into the high

school social studies curriculum (1999, 81 pp.) LRC # 445563

$10.00 ea

□ Classroom Management: A Thinking and Caring Approach Written by Barrie

Bennett and Peter Smilanich, this manual outlines numerous strategies that

teachers can use to cope with misbehaviour in the classroom and create a

learning environment that encourages student learning (1994, 342 pp.)

LRC # 445660

$31.60 ea

□ SACSC series of six full-color posters

A series of six full-color posters highlighting the key SACSC concepts.

LRC # 444836

$ 9.00 ea

PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE

24

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

III. TOWARD A SAFE AND CARING PROFESSION

SACSC trains inservice leaders and workshop facilitators. The following workshops

are designed to help teachers implement the curriculum resources.

□ Toward a Safe and Caring Curriculum—ATA Resources for Integration:

Kindergarten to Grade 6*

□ Toward a Safe and Caring Secondary Curriculum—Approaches for

Integration*

IV. TOWARD A SAFE AND CARING COMMUNITY

This program area is designed to help all adults who work with children—parents,

teachers, coaches, youth group leaders, music instructors—model and reinforce

positive social behaviour, whether at school, at home or in the community. The

community program includes a series of 2-2½ hour workshops for adults and older

teens.

•

•

•

•

•

•

Living Respectfully*

Developing Self-Esteem*

Respecting Diversity and Preventing Prejudice*

Managing Anger*

Dealing with Bullying*

Working It Out Together — Resolving Conflicts Peacefully*

□ Who Cares? Posters (Pkg of 30) LRC # 444654

$ 9.80 ea

□ Who Cares? CD-ROM and brochure

Describes the Safe and Caring Communities Project, a collaborative effort

between the ATA and the Lions Clubs of Alberta (1998) LRC # 444646

$ 4.35 ea

□ Who Cares? video and brochure

Describes the Safe and Caring Communities Project, community program

$ 5.95 ea

(1997, 11 minutes) LRC # 444638

□ Toward a Safe and Caring Community Workshops Action Handbook: A

Guide to Implementation

Provides specific information about how to implement the ATA’s Safe and Caring

Schools Project—Toward a Safe and Caring Community Program. In addition, the

handbook provides suggested activities and strategies to help communities

continue to work on issues related to enhancing respect and responsibility among

$ 7.00 ea

children and teens. LRC # 455304

□ Violence-Prevention Catalogue of Alberta Agencies’ Resources

Compilation of the information that was gathered from over 200 organizations and

community groups who work in the area of violence prevention, and with children

and youth in character development through community leadership.

LRC # 455312

$ 7.00 ea

PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE

Class Meetings for Safe and Caring Schools

25

SACSC PROMOTIONAL ITEMS

□ SACSC cards with color logo and envelopes (Pkg of 40)

Blank card and envelope, featuring the SACSC logo LRC # 444547

$ 10.00 ea

□ Niska hand puppet Featuring the Niska mascotLRC # 444555

$ 14.00 ea

□ Niska labels (800 peel & stick labels per pkg) Featuring the Niska mascot

# 444571

$ 4.00 ea

□ Niska mouse pad 8 ½” by 9 ½” featuring the Niska mascot

LRC # 444563

$6.00 ea

□ Niska tattoos (125 per pkg) A 1½” by 1½” temporary tattoo featuring Niska

$23.40 ea

LRC # 444597

□ Niska water bottles (5 per pkg) 5 white plastic water bottles featuring the Niska

logo LRC # 444612

$ 8.50 ea

□ Niska zipper pulls (5 per pkg) Bronze, featuring the Safe and Caring Schools

Logo LRC # 444589

$ 7.75 ea

□ SACSC award buttons (Pkg of 30–2 ¼” buttons) LRC # 444620

□ SACSC coffee mug LRC # 444604

$ 10.00 ea

$ 5.45 ea

□ Safe and Caring Schools and Communities pencils (Pkg of 30)

Inscribed with “Toward a Safe and Caring Community” LRC # 444662 $10.70 ea

□ Niska T-Shirt (white, featuring the Niska mascot front and back)

□ LRC # 444745 adult X-large;

□ LRC # 444737 adult large;

□ LRC # 444729 adult medium;

□ LRC # 444711 adult small;

□ LRC # 444703 youth X-large;

□ LRC # 444696 youth large;

□ LRC # 444688 youth medium;

□ LRC # 444670 youth small

$10.50 ea

□ SACSC men’s golf shirt (white, featuring the Niska mascot)

□ LRC # 444787 X-large;

□ LRC # 444779 large;

□ LRC # 444761 medium;

□ LRC # 444753 small

$24.95 ea

□ SACSC women’s golf shirt

(white, sleeveless, featuring the Niska mascot)

□ LRC # 444828 X-large;

□ LRC # 444810 large;

□ LRC # 444802 medium;

□ LRC # 444795 small

$24.45 ea

PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE

26

The Society for Safe and Caring Schools and Communities

*All workshop materials can be ordered from the SACSC office by

inservice leaders and workshop facilitators who have successfully

completed the training: e-mail office@sacsc.ca, fax (780) 455-6481 or

phone (780) 447-9487.

ISBN 1-897324-14-6