valuable lies - University of Chicago Law School

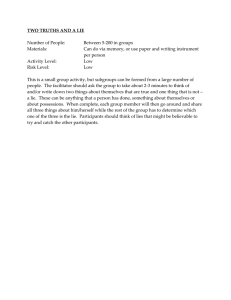

advertisement