`THE SPIRALS OF HIS MIND ARE TIGHTLY WOUND AND

advertisement

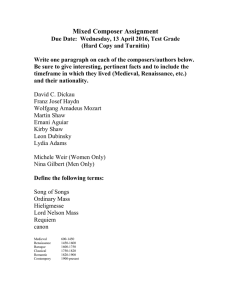

Weinstein, Matthew. “The Spirals of his Mind are Tightly wound and Mysterious: Matthew Weinstein on Jim Shaw at the New Museum.” ARTnews, October 29, 2015. ‘THE SPIRALS OF HIS MIND ARE TIGHTLY WOUND AND MYSTERIOUS’: MATTHEW WEINSTEIN ON JIM SHAW AT THE NEW MUSEUM BY Matthew Weinstein POSTED 10/29/15 11:17 AM Jim Shaw, “The End is Here,” 2015, installation view, at New Museum. MARIS HUTCHINSON/EPW STUDIO The “First Papers Of Surrealism” exhibition, a collaboration between Andre Breton and Marcel Duchamp, was held in New York City in 1942. It was a visual manifesto for the European-born movement, and Duchamp chose for its catalogue cover an image of a piece of Swiss cheese. Aesthetically, the American artist Jim Shaw, whose mid-career retrospective is now on view at the New Museum, can be located somewhere between Duchamp and Breton, and that piece of Swiss cheese. The Swiss cheese catalogue cover, born ten years before Shaw was born, is something he might have produced. Much of his work, starting with his airbrush drawings of the late 1970s and early 1980s, is book sized, illustrative, absurdist, and depicts enigmatic and dreamlike scenarios. It is also deeply indebted to Surrealism. Art historically, in the U.S., Surrealism has tended to get short shrift, its purpose merely laxative: to ease Abstract Expressionism out of the congested, technically academic and hyper intellectual sphincter of European Modernism. (I use this rectal imagery in the spirit of Shaw, in whose work the human digestive tract is often a protagonist). Given its proper due, however, as it was in the Morgan Library’s 2013 show “Drawing Surrealism,” the movement was revealed as a conceptual and stylistic laboratory investigating the relationship between subject and object. In that respect, Shaw is one of Surrealism’s true heirs. His New Museum show is like a scheme for an impossible gesamtkunstwerk by the end of which the mind of the artist dissolves into the object it has striven to construct. Page 1 of 5 Jim Shaw, “The End is Here,” 2015, installation view, at New Museum. MARIS HUTCHINSON/EPW STUDIO Shaw’s interest in Surrealism, and in theatricality, is exemplified by his 2009 room-sized installation Labyrinth; I Dreamed I Was Taller Than Jonathan Borofsky. It consists of theatrical flats that one wanders among like an actor or crew member, privy to the rickety backside of theatrical illusion. The piece has a backstory. It’s dominated by a cut out of the artist Jonathan Borofsky’s sculpture Ballerina Clown, an enormous ballerina with a sad faced clown head that appeared in Venice, California in 1989 as one of the many failed attempts to rehabilitate the neighborhood. Ballerina Clown had a mechanical kicking feature, but the noise from it annoyed Venice residents to the point that the feature was disabled. The piece was restored in 2008 and kicks once again; it presides over the entrance of a CVS. It also presides over the expulsion of the current residents of Venice who cannot keep up financially with the influx of tech industry success stories. The legacy of failure that Ballerina Clown presides over includes the very history of Venice Beach which went from Venetian style beach resort to a place synonymous with people who teach their dogs how to skateboard. The Tower of Babel and a giant humanoid vacuum sucking up the masses are other images of abjection and failure that pile over each other in this installation. It’s moral nature and its inscrutability inclines one to attempt to read it allegorically; good vs evil signified by the rise and fall and rise again of Venice Beach. Surrealism found employment in Hollywood after it became a degraded brand in New York. The Twilight Zone, Ernie Kovacs and Dali and Walt Disney’s film collaboration, Destino (not finished until 2008) are all examples of how useful it was to entertainment. Something of Surrealism of course never left New York, but it is a trace of an impulse that no longer has a name because the word ‘Surreal’ no longer contains specific meaning (it is overused as a synonym for ‘strange’). Jim Shaw’s California Surrealism found a rapt audience among New York artists who, in the ’80s, were searching for a way out of the anti-subjective structures of postmodern discourse. Like those of Joseph Cornell or Lucas Samaras, his artworks are suitcases tightly stuffed with mystery and irrationality. His tight Page 2 of 5 draughtsmanship— a style that bypassed Modernism and evoked a high schooler of prodigious talent who never lost faith in representation–gave us something we had been taught not to like. He has more in common with a medieval monk illuminating religious tomes (stylistically as well as his preoccupation with narratives of good befouled by evil) than with a contemporary artist following the well-worn postmodernist path. Take Shaw’s Dream Drawings, illustrations of other people’s dreams in comic book form. His plain-speak draughtsmanship lends coherent narrative and sequence to the madness of dream space. Dream Drawing (A section in Speed 2 where they’re going thru the ship’s files and come across Penthouse letters files and find my name and there’s a photo of me clothed humping a denim covered globe.”), 1999/2009, is pretty much that. Jim Shaw, “The End is Here,” 2015, installation view, at New Museum. MARIS HUTCHINSON/EPW STUDIO Jim Shaw, “The End is Here,” 2015, installation view, at New Museum. MARIS HUTCHINSON/EPW STUDIO Shaw’s abiding interest in religion is demonstrated in Hidden World, a sprawling installation of his collection of religious material from the margins of faith. It contains Mormon Didactic Photos in which right and wrong are demonstrated by a photo of the moral/safe/good way to do a thing juxtaposed with a photo of the amoral/dangerous/bad way to do a thing. It gets confusing. In one picture, a gleeful child is running down a hallway. In the corresponding one he is shown walking with a robotic expression on his face. Which is right? A highlight of Hidden World is a wall devoted to the accomplishments of Dr. Velma Jaggers (Miss Velma). Miss Velma ‘honors the Lord Jesus Christ with the most beautiful robes and gowns made by leading fashion designers, which she wears in the pulpit to honor the reality of the Lord Jesus Christ…’ etc. Apparently Miss Velma has also been busy creating a tree of life with ‘her artists.’ This tree (in the form of a spooky banyan tree) crops up in Shaw’s film, The Whole, A Study of Oist Integrated Movement, 2009. Oist is Shaw’s invented religion, a blend of New Age, Scientology, Christian Science, Mormonism, and Christianity. It has its own mythology, rituals and even its own entertainment industry. The film possesses the delicious color and sparkly vulgarity of a Douglas Sirk film. A long abstract sequence of sparkles dissolves to reveal a group of dancers with identical bobbed haircuts wearing identically cut chasubles in gauzy fabrics. They awkwardly attempt some Busby Berkeley blooming-flower formations, and then, for no discernible reason, slowly drift over to a spinning artificial banyan tree and pose around it. There is something more than a sendup of Miss Velma’s bejeweled charlatanism going on here. The piece’s circular motions evoke Shaw’s Beckett-like tendency to whirl within his own kinks and preoccupations. Page 3 of 5 I’d rather untangle silly string from a shrub than curate a Jim Shaw exhibition, but New Museum artistic director Massimiliano Gioni and curator Gary Carrion-Murayari have made it look easy. Shaw’s work is laid out in laboratory form, the specimens of his consciousness marshaled into orderly grids within expansive vitrines. But the spirals of Shaw’s mind are left tightly wound and mysterious. Like much viscerally engaging work that takes on the absurd, the abject and the disappointed, Shaw’s work transforms from being about these qualities to being a vessel for them. (The distinction is important.) But there are a lot of laughs along the way, especially in the artist’s collection of found thrift store paintings. These had a huge impact on painters and conceptualists alike when they were first shown in New York in 1991. The iconic painting among them is a Protestant homemaker apparently experiencing the first ecstasies of demonic possession–she’s Shaw’s Mona Lisa. Shaw is like that boyfriend from the West Coast who comes to New York, expertly tinkers with your heart and Jim Shaw, Dream Drawing (“A Section in Speed 2 where they’re going thru the mind, and, the moment you are about ships files and come across Penthouse letters files and find my name and there’s to integrate him into your day-to-day a photo of me clothed humping a denim covered globe.”), 1999/2009, pencil on life, sends you a text from the airport: paper. COURTESY GALERIE PRAZ-DELAVALLADE, PARIS/COLLECTION he is going to India to get his yoga certiROSANA AND JACQUES SÉGUIN, SWITZERLAND fication. But he’s no flake, he just doesn’t fit into your timeline. The volume and virtuosity of his work signify a solid work ethic. Shaw shows us that art is work, and he does not apply cooling filters over his sweaty industriousness. He is therefore, for many of us artists, an inspiring presence. He stands for the idea that art is made in the studio and released into the world as raw material for thought; it isn’t bound by conventional notions of consistency, style, rationality or connectedness to the conventional timeline of art history. Page 4 of 5 In today’s hyper-professional art world, where an artist’s output is marketed in much the same pseudo rational manner as a new sports drink or denim label, Shaw makes a show of artistic backbone. While many artists are saying ‘here is THE thing,’ Shaw is saying, ‘here are a lot of things.’ This attitude towards art produces a generously heterogenous realm of conceptual play that is both hilarious and melancholy. It accesses a rich range of experience; it utilizes and exercises our potential to think on many levels simultaneously. His work’s surreality is unvarnished, ragged, prodigal and tossed back into a culture that has grown accustomed to its absence. The mind, it announces, may be a terrible thing to waste, but it is also a terrible thing to have. Matthew Weinstein is an artist based in New York. “Jim Shaw: The End is Here” runs through January 10, 2016 at the New Museum. Page 5 of 5