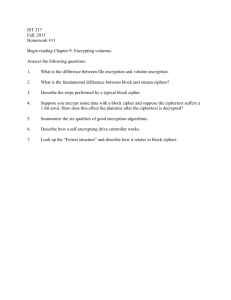

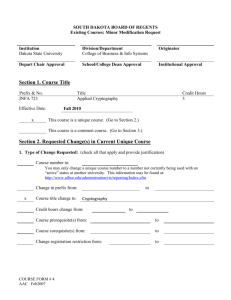

The Use of Encrypted, Coded and Secret Communications is an

advertisement