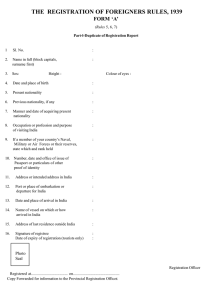

Draft Articles on Nationality of Natural Persons in relation

advertisement