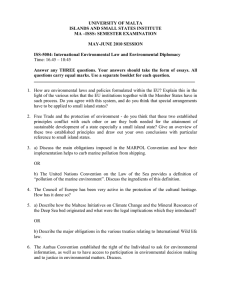

Invoking State Responsibility in the Twenty

advertisement