Unipolar, Bipolar or Borderline: How do you tell what`s

advertisement

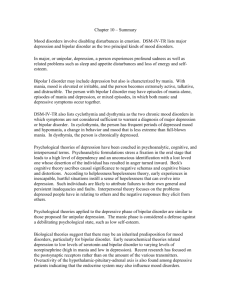

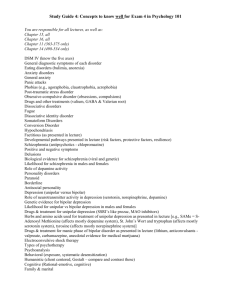

Unipolar, Bipolar or Borderline: How do you tell what’s what… A Guide for Clinicians John P. Hendrick, M.D., DFAPA Associate Professor of Psychiatry, ETSU Chief, Inpatient Psychiatry, Mountain Home VAMC Site Coordinator for Psychiatric Residency ‐ VA/ETSU Residency Training Coordinator for Neurosciences and Psychopharmacology Facts about depression • Affects about 10% of the U.S. population with nearly three out of four in the workplace (Gemignani, 2001) – Incidence • 15 to 25% of the overall population ‐ Prevalence • Prevalence among school age children and adolescents is 4.6% (Wagner, 2003) • Millions do not seek treatment due to inadequate benefits and the stigma associated with depression (U.S. Surgeon General, 2000) • < 25% under the care of a mental health specialist • Twice as common in women • Peak incidence during primary reproductive years (25 to 45 yrs) • Effective pharmacotherapy combined with psychotherapy has been shown to reduce healthcare costs and the rate of suicide attempts (Ballenger, 1999) • Average disability length as well as disability relapse are greater for depression than most comparison medical groups (Conti and Burton, 1994) How can a primary care doc make a reasonable psychiatric differential diagnosis? • Language: – Symptoms – Diagnostic categories • DSM-IV: – 6484 signs, symptoms, inclusion criteria – 405 diagnoses – 18 diagnostic categories • DSM-IV PC starts the process but is inefficient and “psychiatric” Mood Disorders • Major Depression – Single episode – Recurrent • Dysthymia • “Double” Depression • Bipolar Disorder – Mania – Hypomania (Type II ?) • Psychotic Depression (especially post partum psychosis) • Depressive Disorder NOS (Seasonal Affective Disorder) • Cyclothymia • Mood Disorder secondary to GMC • Substance‐Induced Mood Disorder • Adjustment Disorder (separate classification) Common Causes of Depression CHAIN OF EVENTS • Stress & loss • Biological depression • Physical illness and its treatment interact with depression in older adults Recent Loss ___ recent relocation? ___ change in relationships? ___ change in health? ___ change in functional abilities? ___ change in sensory status? ___ change in financial status? ___ death of loved one? (even a pet) ___ loss of control over daily routines? ___ loss of significant role, change in social status? ___declining social contacts due to health limitations EPISODE OF DEPRESSION RECOVERY OR REMISSION NORMAL MOOD DEPRESSION TIME 6 - 24 months 5-1 Stahl S M, Essential Psychopharmacology (2000) Major Depression – Questions: • How is your mood? • Have you been feeling sad, blue or depressed? • Have you lost interest in or do you get less pleasure from the things you used to enjoy? • Has there been any change in your appetite? (5% weight change in 1 month) • How have you been sleeping? • How has your energy level been? • Have you been more fidgety? • Have you felt slowed down, like you were moving in slow motion or stuck in mud? • How have you been feeling about yourself? • Have you been blaming yourself for things? • Have you had problems thinking or concentrating? Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) • >2 week period of change in behavior with 5 of the following: – – – – – *depressed mood *anhedonia appetite disturbance sleep disturbance psychomotor disturbance (sluggish behavior, tearfulness) – – – – fatigue or loss of energy worthlessness or guilt impaired concentration suicidal thoughts • * 1/5 symptoms must be these • Rule out physical causes MINOR Depression (Dysthymia) People with this illness are mildly depressed for years. They function fairly well on a daily basis but their relationships suffer over time. • Also known as – subsyndromal depression – subclinical depression – mild depression • 2 ‐ 4 times more common than major depression • Associated with: – subsequent major depression – greater use of health services – reduced physical, social functioning – loss of quality of life • Responds to same treatments! NORMAL MOOD DYSTHYMIA DEPRESSION 2+ years 5-7 Stahl S M, Essential Psychopharmacology (2000) DOUBLE DEPRESSION NORMAL MOOD DYSTHYMIA 2+ years 5-8 DEPRESSION PARTIAL RECOVERY 6 - 24 months Stahl S M, Essential Psychopharmacology (2000) Depression. It’s not only a state of mind. The symptoms of depression Emotional Symptoms Include: Physical Symptoms Include: Sadness Vague aches and pains Loss of interest or pleasure Headache Overwhelmed Sleep disturbances Anxiety Fatigue Diminished ability to think or concentrate, indecisiveness Back pain Excessive or inappropriate guilt Significant change in appetite resulting in weight loss or gain Reference: Adapted from American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition ,Text Revision. Washington, DC; American Psychiatric Association. 2000:345‐356,489. Pain perception • • • • “Is it all in my head?” Emotional aspects of pain Biology of pain perception Cultural factors Depression – the physical presentation In primary care, physical symptoms are often the chief complaint in depressed patients In a New England Journal of Medicine study, 69% of diagnosed depressed patients reported unexplained physical symptoms as their chief compliant1 N = 1146 Primary care patients with major depression Reference: 1. Simon GE, et al. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(18):1329-1335. The importance of emotional and physical symptoms • 76% of compliant depressed patients with lingering symptoms of depression relapsed within 10 months1* 94% of depressed patients who experienced lingering symptoms had mild to moderate physical symptoms1 *Psychiatric inpatients and outpatients. Reference: 1. Adapted from: Paykel ES, et al. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1171-1180. Treatments • • • • • • Pharmacotherapy Psychotherapy Social interventions ECT TMS VNS Treatment outcome: Effect on work & social functioning Social Adjustment Scale-SR (Mean ± SD) Higher Score indicates greater impairment Remitted patients virtually equaled healthy controls on functioning levels at endpoint of 12-week treatment trial (Responders & non-responders did not) 5 3 * ** 2 * 1 Normal (n=482) Study in chronic depressed patients *p.05 vs nonresponse. **p.05 vs response. Miller IW, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(11):608-619. Remission (n=202) Response (n=122) Nonresponse (n=299) Statistics • 60‐70% tolerant patients respond to 1st line monotherapy • Up to 50% treated with single antidepressant don’t reach full remission • 1/3+ become treatment resistant Available Types of Pharmacotherapy But Which Medication? • Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) • MAOI’s • SSRI’s • SNRI’s • Atypical antidepressants • Mood stabilizers • Antipsychotics • • • • • Safety Tolerability Efficacy Payment Simplicity SSRIs • Used first because of high tolerability/ low toxicity • No response from SSRI 1 or 2 (or intolerable) ‐What’s the next step? Med switches? Augmentation? Novel or Atypical Antidepressants • Bupropion (NE and DA reuptake inhibition) • Trazodone (5 HT2 alpha‐ ANT) • Venlafaxine and Duloxetine (NE and 5 HT reuptake blockers – SNRI’s) • Mirtazapine (presynaptic alpha 2 ANT and 5 HT2 and 5 HT3 ANT) Med Switches • 1 in 4 patients on SSRI’s have a response on 2nd drug: • Within class 1st SSRI may be ineffective/ intolerable 2nd SSRI may be effective/ tolerable • Out‐of‐class • Dual‐action agent Augmentation • Sustained release bupropion group • Buspirone group Similar response and remission rates BUT Bupropion had greater symptom reduction and tolerability • Quetiapine in 150 ‐200 mg dose as adjuvant therapy Many depressed patients are still depressed. Depressed patients continue to have needs that are not being fully addressed1 • Depressed patients present with emotional and physical symptoms. • Approximately 30% of depressed patients achieve remission in clinical trials2* • Up to 70% of patients who respond fail to remit2* • Incomplete relief from symptoms may increase the risk of relapse2,3 • Lingering emotional and physical symptoms may jeopardize achieving remission. References: 1. Nierenberg AA, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999:60(suppl 22):7-11. 2. O’Reardon JR, et al. Psychiatr Ann. 1998;28:633-640. *In antidepressant clinical drug trials. Lynch ME. 3. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26(1):30-36. Pseudoresistant • Inadequate dosing/ early treatment discontinuation • Patient noncompliance • Misdiagnosis General Treatment Rules • Often takes 4‐6 weeks for response • Monitor for response versus remission • Vegetative symptoms tend to improve first, cognitive symptoms take longer • SSRI’s are the first line of treatment for most MDD’s • Address biopsychosocial needs and maintain meds for 6‐12 months Psychotherapy in Depression • • • • • • Supportive Insight‐oriented Interpersonal Cognitive‐behavioral Psychodynamic Individual, group or family Resources & Abilities ___ family support? ___ community support? ___ social network? ___ physical abilities? ___ functional abilities? ___ cognitive abilities? ___ financial resources? ___ personality traits? personal history? ___ experiences, beliefs, convictions? Promote Autonomy • Create mastery experiences – break tasks into steps – assure success – promote self worth, build confidence • Encourage personal control, power – independent activity – decision‐making – involvement in care Focus on Positive • Current abilities – – – – knowledge, wisdom experiences attitudes, beliefs attributes • Reminiscence – promotes self worth – strengthens tie to identify, “former self” – stimulates interests, conversation Encourage Group Activities • Psychosocial therapies – – – – Reminiscence Remotivation Health, stress management Sensory stimulation • Many benefits – Social interaction – Mastery experiences – Realization “I am not alone in this! Promote Creativity • Lots of alternatives: – – – – – Singing, playing music Story‐telling Drawing, painting Poetry, writing Making crafts, jewelry • Associated with positive health outcomes – Decreased depression, loneliness – Increased health, morale, satisfaction, activity Enhance Social Support • Identify a “point person” to help identify, mobilize resources – – – – – – family member friend, neighbor church members clergy volunteer visitor peer counselor Things to Avoid • Don’t make long‐term commitments or important decisions unless necessary • Don’t assume things are hopeless • Don’t engage in “emotional reasoning” (i.e.: because I feel awful, my life is terrible) • Don’t assume responsibility for events which are outside of your control • Don’t avoid treatment as a way of coping Bipolar Disorder • People with this type of illness change back and forth between periods of depression and periods of mania (an extreme high). • Symptoms of mania may include: ‐Mood changes are usually gradual, but can be sudden ‐Less need for sleep ‐Overconfidence ‐Racing thoughts ‐Reckless behavior ‐Increased energy New Concepts of Bipolar Disorder • Life‐threatening medical illness • Lifelong medical illness • Lifelong treatment warranted • Akiskal asserts at least 50% of depressions are bipolar at some level Potentially 8 Identifiable Patterns • Bipolar I (Classic Pattern) ‐ 40 – 50 % of episodes are dysphoric Percentage of dysphoria is much higher in the psychotic condition • Bipolar II (Sunny) ‐ Recurrent anergic depression with hypomania often on tail end of a depression • Bipolar II ½ (Dark) ‐ Female preponderance, Panic and social phobia often comorbid, Suicide seems increased, Easily misidentified as Borderline PDO • Bipolar III (Switch Sensitive Doubles) ‐ Hypomania in response to antidepressant therapy, Often tempermentally dysthymic and may be a “double depressive” • Bipolar III ½ (Agitated Alcoholism) ‐ Excitement and minor depressions closely linked to alcohol abuse, sometimes in abstinence, Combination treatments useful • Bipolar IV (Executive) ‐ Depressive episodes overlaying a hyperthymic temperament, males with Type A personality characteristics‐“narcissistic” PDO misdiagnosis • Bipolar V (Borderline Mimic) ‐ High recurrence rate (>5 episodes), Positive family history, Hypomania overlays depression in a “mixed” fashion, Positive family history • Bipolar VI (Late Onset) ‐ Patients have early dementia, Mood instability, sexual • disinhibition, agitation and impulsive behavior, Antidepressants may aggravate symptoms Remote history of hypomanic episodes or positive family history may be present (collateral information), May be responsive to divalproate or ACD mood stabilizers,Worsen on antidperesants, Increased importance with dementia/atypical black box Mania and Hypomania - Questions: • Have there been times lasting at least a few days when you felt the opposite of depressed, that is when you were very cheerful or high and felt different than your normal self? • Did you feel hyper, or like you were high on drugs, even though you hadn’t taken anything? • Did anyone notice there was something different? • How long did it last? • What was your selfesteem like? • During this time did you sleep? • Were you more talkative than usual? • Did it feel like your thoughts were going very fast and racing through your mind? • Were you easily distracted? • Were you more active than usual? Bipolar Disorder • Lifetime prevalence1 – BP I = 1.0%‐1.6% – BP II = 0.5% Probably underestimated • 90% recurrence2 • Number of episodes correlates with residual symptoms between episodes and response to treatment2 • 25%‐50% of patients attempt suicide2 – 15% suicide rate1 • High comorbidity—eg, substance abuse1 1. Evans. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 13):26. 2. Brady. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 13):32. MANIA MIXED EPISODE HYPOMANIA NORMAL MOOD DEPRESSION 5-5 Stahl S M, Essential Psychopharmacology (2000) Bipolar Depression • 80% of patients exhibit significant suicidality • 60% of patients with dysphoric mania exhibit suicidality • Depressive episodes dominate course of bipolar disorder (twice the amount of time as in mania) • 25‐30% of patients initially diagnosed with unipolar depression subsequently have a manic or hypomanic episode • 50% of first bipolar episodes are depressive episodes • Depressive episodes in bipolar disorder are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality • Bipolar depressive episodes have a chronic course Goodwin FK and Jamison KR. Manic Depressive Illness Impact of Bipolar Disorder Vs. Unipolar Disorder — Heavy Impact on Daily Life 54 * 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 48 * MDQ positive MDQ negative 29 23 26 * 5 Ever Fired or Laid Off * P<0.0001 Calabrese. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:425-432. Supervisor Unhappy With Work, Behavior, or Attitude Jailed, Arrested, or Convicted of a Crime Other Than Drunk Driving Epidemiology • 15% to 20% of untreated patients succeed in committing suicide1 • High recurrence rate of bipolar disorder2 • High economic burden2 • Bipolar is a multidimensional disease1,3 1Evans DL. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(suppl 13):26‐31 2Woods SW. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(suppl 13):38‐41 3Goodwin FK et al. In: Goodwin FK, Jamison KR, eds. Manic‐Depressive Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;1990:74‐84 Treatment Challenges in Bipolar Disorder Predictors of Suicide in Bipolar Disorder • High Impulsivity • Alcohol and Substance Abuse • DEPRESSION and MIXED Episodes • History of Abuse in Childhood • Exacerbated by incorrect treatment • • • • • Often unrecognized Often untreated Often misdiagnosed Often inadequately treated Exacerbated by incorrect treatment Akiskal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16(suppl 1):4S-14S. BIPOLAR DISORDER The Major Challenge: Misdiagnosis NDMDA survey of its bipolar members Rate of misdiagnosis 1994 2000 73% 69% Most frequent misdiagnosis: Unipolar depression Treatment as unipolar depression can lead to worsening of symptoms by switching into mania or cycle acceleration Goodwin & Jamison (1990); Hirschfeld et al (2003); Lish et al (1994) Physician Diagnoses Among MDQ Positives in the Community Dx with bipolar disorder 20% Neither bipolar disorder nor depression Dx 49% 31% Dx with depression but not bipolar disorder 80% of patients who screened positive for BP were not diagnosed w/ BP Hirschfeld RMA, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:53-59. Steps to Increase Recognition of Bipolar Disorder and to Improve Diagnosis • Education of physicians about the illness, particularly how it presents itself in clinics • Ask patients directly about history of symptoms of Bipolar Disorder • Involve family members in clinical evaluations • Increase patients’ and families’ awareness of the illness • Screen for Bipolar Disorder, especially in depressed patients The Evolution of Therapies for Acute Mania/Hypomania 1940 ECT *Approved 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2002 Lithium* First-generation antipsychotics Second-generation antipsychotics Chlorpromazine* Trifluoperazine* Fluphenazine Thioridazine Haloperidol Mesoridazine Clozapine Risperidone Olanzapine* Quetiapine Ziprasidone Anticonvulsants Anticonvulsants Carbamazepine Valproate* Gabapentin Lamotrigine Topiramate Oxcarbazepine for use for acute mania. McElroy and Keck. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:539. Nemeroff. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(suppl 13):19. Next-generation antipsychotics Aripiprazole Why are SOME Anticonvulsants Mood Stabilizers? Valproate, Carbamazepine, Oxazapine, Lamotrigine, Clonazepam • Reducing glutamate and increasing GABA transmission potentially – Raises the seizure threshold – Reduces overstimulation – Prevents or inhibits behavioral sensitization – Prevents or inhibits kindling • Yet not all anticonvulsants are mood stabilizers Other ANTICONVULSANTS • • • • • Gabapentin Pregabalin Levetiracetam Tiagabine Topiramate NO PROVEN EFFICACY Treatments with Evidence for Effective Continuation Try to use treatments with evidence for relapse prevention in patients who have responded to the drug: – Lithium – Divalproex – Atypicals: olanzapine has best evidence – Combination of lithium or divalproex with olanzapine or risperidone Valproate / Divalproex • Uses – acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder – ? bipolar depression • Advantages – better tolerability than lithium – can be loaded rapidly – once‐a‐day formulation available • Disadvantages – drug‐drug interactions – fetal abnormalities Appropriate Use of Monotherapy • 30 ‐ 40% of patients succeed on monotherapy • Complex regimens –Are expensive –May decrease adherence –Pose difficulty in elucidating which medications are beneficial and which cause side effects Bowden CL, et al. JAMA. 1994;271:918‐924. When Monotherapy Is Not Enough • Many patients remain symptomatic on monotherapy • After patients are treated with the right dose for an adequate time period, assess symptom response • Combination therapy may be required – Acute psychosis, bipolar mania, and bipolar depression – Maintenance treatment for full symptom remission Choosing Treatment • Episode characteristics – Pure, uncomplicated mania: favorable response to all treatments – Predictors of poor lithium response: • Severity; psychosis • Mixed/depressive features • Complications • Past history – Unstable course of illness – History of complications (e.g., head trauma, substance abuse) predisposes to mixed states Selection of Treatments • Start with proven treatments • Use response predictors • Identify and monitor target symptoms • Assure adequate dose and time • Additional/new treatments based on evidence and feasibility • Collaborate Finding the Best Dose • Establish diagnostic context and target symptoms • Priorities: is time of the essence? • Increase dose to maximum that is tolerated • Evaluate response and toleration – Not improving: tolerating or not? – Improving: if levels feasible, steady‐state level as benchmark • Primary consideration is how the patient responds, not dose or level If Patient Response is Inadequate • Tolerating: increase dose • Not tolerating or extenuating circumstances – Augment – Reduce dose and augment – Switch to another treatment • Augmentation – Drug with complementary mechanism – Pharmacokinetically compatible – A drug that you are comfortable giving the patient for at least six months, or preferably indefinitely Lamotrigine in Acute Treatment of Bipolar Depression Change From Baseline of MADRS LTG 50 mg/day (n = 64) LTG 200 mg/day (n = 63) LOCF Observed 0 0 -5 -5 -10 Placebo (n = 65) * † * † -15 -10 † † † † † -20 † † -15 † † † † -20 0 1 2 3 4 Week 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 Week * P<0.1; † P<0.05. LOCF = last-observation-carried-forward. Calabrese et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:79-88. 5 6 7 Strategy and Time Course Acute 0 - 8 weeks Continuation 1 - 6 months Maintenance Indefinite Syndromal recovery Functional recovery Maximized function; stability Maximize moodstabilizers; adjunctive treatments Optimize tolerability; taper adjunctive when possible Optimize; anticipate prodromes Support/structure; education; involve family Behavioral; systems; Strategies to institute monitoring optimize adaptation Sachs et al. J Clin Psychopharm 1996. 16(2suppl1):32s-47s; Tohen et al. Am J Psychiatry 2000. 157:220-228. Anticipating an Episode • Prodromes weeks‐months before episodes consistent within individuals – Smith & Tarrier. 1992. Soc Psychiat Psychiat Epid 27:245‐248. • Look for early changes in the underlying illness – Motivated activity – Sleep‐activity cycle – Impulsivity – Interpersonal behavior – Affect – often is a later indicator Consequences Of Premature Treatment Discontinuation Probability of Remaining in Remission (%) 100 Lithium or valproate + olanzapine (n = 30); Li = 0.78, VPA = 69.2 Lithium or valproate monotherapy (n = 38); Li = 0.75, VPA = 67.6 80 60 * 40 *P = 0.023 Early relapse when part of treatment was withdrawn 20 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 Time to Recurrence of Mania or Depression (days) Subjects had reached remission on combination treatment and were randomized to have olanzapine withdrawn or continued Tohen ME, et al. Br J Psychiatry, 2004. Long‐term Antidepressants in Bipolar Disorder • No evidence for relapse prevention in controlled studies – Ghaemi • Patients who required antidepressants for an acute episode (15‐20% of patients) appeared to benefit from 6‐12 months continuation – Altshuler L et al. Am J Psychiatry 2003(July):160(7):1252‐1262. • Pattern of poor response/loss of response – Sharma et al. J Affect Disord 2005:84:251‐257. • Development of irritable dysphoria during long‐term treatment – El‐Mallakh & Karippot. J Affect Disord 2005:84:267‐272. Combinations • Lithium plus valproate • Atypical plus lithium/valproate – – – – Risperidone Olanzapine Quetiapine Combination therapy appeared more efficacious, but doses of mood stabilizer were often inadequate • Antipsychotic plus valproate – Valproate addition reduced antipsychotic dose and improved outcome Valproate Reduces Neuroleptic Requirement in Mania 120 Neuroleptic % Dose 100 80 60 Placebo Valproate 40 20 0 0 5 10 15 20 Day Muller-Oerlinghausen et al. J Clin Psychopharmacology 2000;20:195-203. 25 Summary of Combination Therapy for Acute Mania in Bipolar Disorder • Combination therapy is efficacious in treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder – Divalproex and lithium – Divalproex or lithium and atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine) – Divalproex or lithium and typical antipsychotics (haloperidol) • Combination therapy randomized, controlled studies that included lithium and/or divalproex used suboptimal doses, yet demonstrated increased efficaciousness with these agents • Combination therapy with divalproex could result in lower doses of antipsychotic agent • Divalproex and lithium are the foundation of bipolar therapy Switch Rates on Antidepressants • All antidepressants while on mood stabilizers • High rates of switch (over 10% short term) – TCA’s, venlafaxine, MAOI’s • Low rates of switch (under 10% short term) – Bupropion, SSRIs • Much higher if not on a mood stabilized • Paroxetine is the most well studied: three double blind studies • All add‐on • All double blind against placebo, imipramine, venlafaxine, and combined lithium and divalproex Young et al., Am J Psychiatry 2002; Nemeroff et al., Am J Psychiatry 2001; Vieta et al., J Clin Psychiatry 2002 ON THE OTHER HAND Depression Following Antidepressant Discontinuation in Bipolar Patients (Chart Review) 100% % Well ( Not Depressed) 90% Continued Antidepressant n=19 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% Discontinued Antidepressant n=25 20% 10% 0% 0 13 26 Weeks After Improvement Altshuler et al., J Clin Psychiatry, 2001; 62:612-616. 39 52 Psychosis Is Common in Bipolar Disorder • Two‐thirds of patients have at least 1 psychotic symptom. • All forms of psychosis, including mood‐ incongruent, bizarre, Schneiderian first‐ rank symptoms, formal thought disorder, and catatonia may occur in Bipolar I disorder. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic‐Depressive Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 1990; Tohen M, et al. Am J Psychiatry 1992. Strategies for Reducing Suicidal Risk • • • • • Prevent episodes, especially depressive, mixed (Swann 2000) Reduce impulsivity and substance abuse (Corruble 1999) Lithium more effective than carbamazepine in treating classical bipolar cases (Greil 1998) Lithium, divalproex equally effective in pure manic patients; divalproex more effective than lithium in patients with mixed mania or psychotic symptoms in only controlled study (Bowden 1998) Provide structured, supportive therapeutic relationship (Vestergaard 1991) Swann AC. 2000; Corruble E, et al. J Affect Disord 1999; Greil W, et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1998; Bowden CL. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; Vestergaard P, Aagaard J. J Affect Disord 1991. APA Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder Maintenance Treatment • Medication with the best evidence for maintenance – Lithium and valproate – Alternatives include lamotrigine or carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine – Maintenance ECT may also be considered • • Antipsychotics should be discontinued unless required for persistent psychosis or prophylaxis against recurrence While maintenance with atypical antipsychotics may be considered, no definitive evidence comparable to lithium or valproate • Likely benefit from concomitant psychosocial intervention – Psychotherapy to address illness management (adherence, lifestyle changes, early detection of prodromal symptoms) and interpersonal difficulties • Group therapy may also address adherence, adaptation, self‐ esteem, and personal and psychosocial issues • Support groups provide useful information about bipolar disorder and its treatment American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(Suppl 4):1‐50. Summary • Maximize standard mood stabilizers, including combination. • Utilize anxiolytic/hypnotics, atypical neuroleptics, and novel anticonvulsants as mood stabilizers to adjunctive therapy. • Brief, acute intermittent antidepressant treatment. • Address psychoeducational needs. The “Big 5” Personality Traits Openness to experience (v. premature closures) Conscientiousness (v. irresponsibility) Extraversion (v. introversion) Agreeableness (v. uncooperativeness) Neuroticism (v. a healthy world view and positive adjustments) personality disorders represent extreme variations of OCEAN Main Features of PDs • Extreme patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving that deviate from a person’s culture • Listed on Axis II of the DSM‐IV‐TR • Begin early in life and remain stable • Not contextual or transient, Little behavior change over time • Inflexible and maladaptive, Effects behavior in many situations • Cause significant functional impairment and subjective distress • Ego‐syntonic vs. ego‐dystonic • Causes distress in others due to dysfunctional theory of mind • Onset usually late childhood, early adolescence • Pathological uncooperativeness, Poor insight Personality Disorders require 3 overarching characteristics: What are they? Personality Disorder ‐ Inflexible patterns of behavior (maladaptive) ‐ Begins early in adulthood (lifelong) ‐ Results in social, occupational problems or distress (pervasive) Cluster A Cluster B Cluster C Odd, Eccentric Angry Anxious Cluster A Personality Disorders Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders Marked by eccentricity, odd behavior, not psychosis Share a superficial similarity with schizophrenia (as if a milder version) Cluster C Personality Disorders Avoidant, obsessive‐compulsive, dependent disorders Individuals are often anxious, fearful, and depressed Cluster B Personality Disorders Antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders Being self‐absorbed, prone to exaggerate importance of events Having difficulty maintaining close relationships Poor capacity to engage in ongoing cooperative relationships Primary Cluster B Personality Disorders John Gunderson, MD • • • • • Borderline NOS 22% Narcissistic Antisocial 7% Histrionic 1% 56% 14% • • • • Psychotic Borderline The Borderline Syndrome The As – If Borderline The Neurotic Borderline “Borderline Personality Organization” ‐ Kernberg Grinker, Werble and Drye, 1968 BORDERLINE PD Unstable Relationships, Affect Disturbance, Dysfunctional Self‐Image Plus Impulsiveness AND 5 + of : • Fears Abandonment • Mood Shifts (Affective Instability, hours, even minutes) • Unstable Relationships Feels Empty • Changing Self‐Image • Impulsive Sex, Spending • Identity disturbances • Recurrent suicidal or self‐mutilating behavior • Feelings of emptiness • Inappropriate intense anger • Transient paranoia or dissociation • Paranoia Borderline and comorbidity • High degree of overlap with both Axis I and Axis II disorders • 24%‐74% also diagnosed with major depression; 4% to 20% bipolar • 25% of bulimics also diagnosed with BPD • 67% also diagnosed with substance use disorder Splitting A primitive defense. Negative and positive impulses are split off and unintegrated. Fundamental example: An individual views other people as either innately good or innately evil, rather than as a whole continuous person. * Tellin’ a man to go to hell and makin’ him do it are two entirely different propositions Acting Out Acting Out is performing an extreme behavior in order to express thoughts or feelings the person feels incapable of otherwise expressing. Instead of saying, “I’m angry with you,” a person who acts out may instead throw a book at the person, or punch a hole through a wall. When a person acts out, it can act as a pressure release, and often helps the individual feel calmer and peaceful once again. For instance, a child’s temper tantrum is a form of acting out when he or she doesn’t get his or her way with a parent. Self‐ injury may also be a form of acting‐out, expressing in physical pain what one cannot stand to feel emotionally. Projective Identification Projective Identification refers to a psychological process in which a person engages in the ego defense mechanism projection in such a way that their behavior towards the object of projection invokes in that person precisely the thoughts, feelings or behaviors projected. Projective identification differs from simple projection in that projective identification is a self‐fulfilling prophecy, whereby a person, believing something false about another, relates to that other person in such a way that the other person alters their behavior to make the belief true. The second person is influenced by the projection and begins to behave as though he or she is in fact actually characterized by the projected thoughts or beliefs. This is a process that generally happens outside the awareness of both parties involved, though this has been debated. So…When you give a lesson in meanness to a critter or a person, don’t be surprised if they learn their lesson. Reducing Suicide Risk • Use medicines that reduce recurrence and impulsivity • Work for early recognition of risky internal states and of early signs of recurrence • Dialectical Behavior Therapy • Foster a forward‐looking approach – – – – – – Social structure and contact Sequential, attainable goals Constructive anticipation of changes and problems Responsibility for health and decisions Encourage mindfulness of behavior Construct and observe careful and appropriate boundaries TRUE FALSE Suicide in Older Adults • Represent 13% of the population • Account for 1/5 (20%) of all reported suicides • Lowest rate of ATTEMPTS • Highest rate of COMPLETED SUICIDE Indirect Suicide • Starvation, refusing to eat • Refusing needed medications • Mixing medications • Alcohol abuse • Loss of “will to live” Poor Outcomes Comorbid Conditions • Anxiety • Medical problems • Cognitive impairment Concurrent Problems & Issues • Psychotic depression • Impaired social support • Stressful life events • Multiple previous episodes Incidence of Post Stroke Depression • Approximately 1/3 of persons will experience clinically significant depression at some point following a stroke. Hacket, et al., 2005 • Robinson found that 19.3% and 18.5% of stroke survivors had major depression or minor depression, respectively, in acute care rehabilitation settings. Robinson, RB, 2003 • No significant difference in incidence between hemorrhagic and infarct strokes Distinguishing types of crying: • Pathological crying linked to infarct in basis of pontis and corticobulbar pathways and occurs in response to mood incongruent cues. • Emotionalism is crying that is congruent with mood (sadness) but patient is unable to control crying as they would have before stroke. • Catastrophic reaction is crying or withdrawal reaction triggered by a task made difficult or impossible by a neurologic deficit (e.g. moving a hemiplegic arm) LONG TERM CONSEQUENCES OF POSTPARTUM MAJOR DEPRESSION • Babies of mothers with PMD were perceived by their mothers as more difficult to care for and more bothersome. Postpartum Blues • Often viewed as “normal” • Affects 40 to 85% of new mothers • Peaks between postpartum days 3 and 5 • Resolves within 24 to 72 hours • Subsides without treatment by postpartum day 14 • Symptoms: – – – – Sadness, anxiety, irritability Uncontrollable tearfulness Wide mood swings Occasional negative thoughts • Primary Treatment: – Supportive care and reassurance about the condition Postpartum Depression • Difficulty concentrating or making decisions • Psychomotor agitation or retardation • Feelings of worthlessness or guilt (especially focusing on failure at motherhood) • Fatigue • Excessive anxiety • Changes in appetite and/or sleep patterns • Frequently focusing on the child’s health • Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide Postpartum Psychosis Rare condition, affecting 1 to 2 out of 1000 women after childbirth Onset as early as 48 to 72 hours postpartum Presentation can be dramatic Symptoms develop within the first 2 weeks after delivery • Early Symptoms – Restlessness – Irritability – Sleep disturbance • Progressive Symptoms – Depressed or elated mood – Disorganized behavior – Mood swings/ instability – Delusions – Hallucinations Suicide Assessment Always ASK!!! “Have you thought that life isn’t worth living?” If YES, then . . . “Have you thought about harming yourself? If YES, then . . . “Do you have a plan?” If YES, examine lethality. . . Is the plan viable? Can they execute it? Are means deadly, available? References • Blais MA, Smallwood P, Groves JE, Rivas‐Vazquez RA. Personality and personality disorders. In: Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, Biederman J, Rauch SL, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. 1st ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Mosby Elsevier;2008:chap 39. • Borderline Personality Disorder Demystified by Robert O. Friedel, M.D., Marlowe & Co., 2004 • National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder’s Teachers Manual for Family Connections, 2006 • A BPD Brief, An Introduction to Borderline Personality Disorder by John G. Gunderson, M.D., 2006 • A REMINDER for assessing psychosis‐ John Hendrick, MD‐ CURRENT PSYCHIATRY April 2010 Volume 9, No. 4